Katharine McGregor

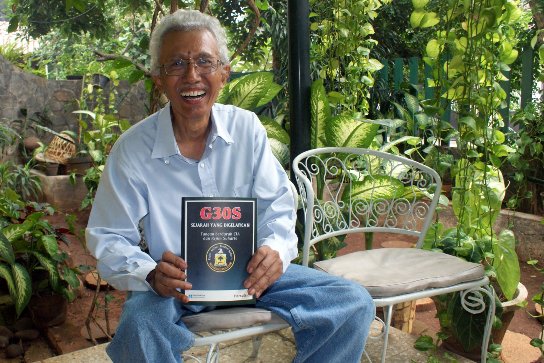

Harsono Sutedjo |

Between 1965 and 1968 half a million Indonesians were killed by the military and civilian vigilantes and hundreds of thousands imprisoned without trial. The purpose of this violence was to eliminate the Indonesian left which had wanted to introduce socialism to Indonesia. The repression targeted not only members of the PKI (Indonesian Communist Party) and affiliated organisations, but also Sukarno supporters from the Indonesian Nationalist Party and the military.

It is thus hard to generalise about the political views of the broad spectrum of people targeted in this violence, including those who survived the killings or imprisonment. Nevertheless, asking the survivors to reflect on the state of contemporary Indonesia is one way we can gauge what was lost from Indonesia’s political life with the destruction of the left, and to look for continuities between earlier and contemporary periods of political struggle. In this article I explore the opinions of one former political prisoner about contemporary Indonesia in order to assess what is left of the Indonesian left.

A life in politics

Harsutejo (Harsono Sutedjo) was born in the late 1930s in Wlingi East Java. His mother was an illiterate farmer who managed an aunt’s rice farm. Although she remained illiterate for life she always stressed the importance of education to Harsutejo. His father was a sugar factory employee who frequently challenged his Dutch boss. He was detained and imprisoned by the Dutch for his activities in the leftist organisation, Sarekat Rakyat (People’s Association) and by the Japanese for his involvement in the underground resistance to Japanese rule. On the second occasion, he was dragged from the bedroom in their family home, stripped naked and kicked in front of the family. The violence of this arrest triggered in Harsutejo feelings of revenge towards colonialists, but also a rejection of violent methods.

When the Japanese period (1942-45) ended his father was released and joined the struggle against the Dutch. Many important figures in the independence struggle (1945-1949) visited Harsutejo’s house when he was a young boy. He was surrounded by talk of politics. When his father was pursued by the Dutch, the family fled to the mountains and lived with another family. Harsutejo worked as a courier for the revolution and witnessed much violence during this period.

In 1953, Harsutejo joined his first organisation, IPPI (Indonesian High School Students and Youth Association). Although IPPI discussed some national issues such as the struggle for the ‘return’ of Western New Guinea (now known as Papua) to Indonesia, his participation in IPPI focused on cultural activities. In 1957, he joined Pemuda Rakyat (People’s Youth), a youth organisation affiliated with the PKI. He continued to be involved in cultural productions like poetry reading, choirs and ensembles as a means of promoting the organisation.

Harsutedjo read widely as a child and he was the only member of his family to complete a university degree. When he began his degree in cultural history at Airlangga University in Malang he joined the student organisation CGMI (Indonesian Student Movement Centre). Again he was involved in cultural activities, but also in protests against the Dutch refusal to surrender the territory of Western New Guinea to the Republic. He recalls being part of a crowd that surrounded a Dutch school in Malang and told the students and staff to go home. By the late 1950s, the Indonesian government had nationalised all Dutch assets and also began to expel Dutch nationals. CGMI activists protested against the Vietnam War and against nuclear weapons. They connected Indonesian struggles to those in similar countries at the time.

After graduating and becoming a lecturer at Airlangga, Harsutedjo joined HSI (Indonesian Graduates’ Association). Like the other organisations he had joined, it opposed imperialism and feudalism and promoted socialism as the best political system. One of their greatest concerns was that Indonesia would become ‘just a puppet state to be used by others’. By the mid-1960s, as President Sukarno leaned increasingly to the left, Harsutedjo recalls that most radicals were convinced that Indonesia would become socialist, or at least implement an Indonesian form of socialism.

Harsutejo was conscious of challenges from conservative groups to all the left-aligned organisations he joined. Yet ‘we felt a sense of strength and that the government was on our side’. Like many other members of mass organisations, Harsutejo was unprepared for the violent assault following the Thirtieth September Movement event. He stated that ‘no-one imagined it would be so bad.’ In his view, they should have been better prepared for such an attack.

Harsutejo was arrested in Malang in 1965 and imprisoned for six months. He fled to Surabaya and then Jakarta so as to avoid the pernicious monitoring the Suharto regime imposed on former political prisoners. After assuming a new identity and cutting all family ties, Harsutedjo worked in a foreign bank for two decades.

Staying steady

In an interview in Bekasi I asked if and in what sense he considered himself representative of the Indonesian left. He responded that he defined himself as a leftist in that he was ‘anti- establishment, anti-feudal, anti-capitalist and anti-bureaucratic’. In short, he is for the people and opposes anything that does not support the people’s interests.

He stated that his basic political views had not changed throughout his life, but he now believed that the way to communicate these ideas should be more moderate. ‘I am probably different to others who think that socialism can be implemented just as we learned in the past. In the Soviet Union it failed. Suryono a former journalist for Harian Rakyat (People’s Daily) said in the Soviet Union the communist party ran the country, but he did not meet one communist.’

Harsutedjo began to have hesitations about the Soviet Union as a model for Indonesia in the 1950s, when he learnt about the violent repression in Poland and Hungary. As for China as model he noted, ‘In the People’s Republic they said they would build communism, they have developed a lot but in the end there is a big gap between the rich and the poor.’

Reflecting on the Indonesian left in the 1960s Harsutejo comments that ‘our methods were too extreme, our language was too strong, it had no nuance. We conceptualised things in black and white’. In this rare critique from a former activist, Harsutejo recalls the dogmatic nature of politics in the mid 1960s as those of the left called for a ‘retooling’ of people who were not sufficiently anti-imperialist or anti-feudalist.

Our methods were too extreme, our language was too strong, it had no nuance. We conceptualised things in black and white.

When asked to compare the pre-1965 period with today’s Indonesia, Harsutedjo commented that ‘the gap between the rich and poor was not so pronounced, while we spoke of capitalist bureaucrats this referred largely to the military and civilians’. He feels that there was a greater sense of social conscience after independence, perhaps because the people were more spirited. From independence onwards there were united efforts, for example, to eradicate illiteracy.

During the Suharto era, Harsutedjo observed the escalation of capitalism in Indonesia from within the system. Working in a foreign bank, an institution that symbolises modern capitalism, he was sometimes frustrated as to how he could achieve change in society. He studied banking laws and attempted to ensure the bank’s policies were fair with regard to Indonesian interests.

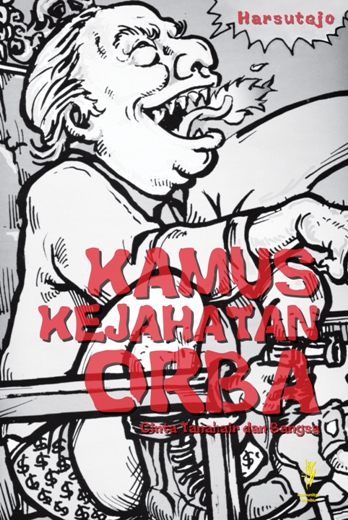

After the fall of Suharto in 1998, Harsutedjo began to publish works about his experiences and about his political views. In 2010 he published a book, Dictionary of the New Order’s Crimes: Love your Homeland and Your Nation. Although the book is focused on the New Order it traces not only the crimes of that regime, but also its enduring legacies. In it, Harsutedjo provides a comprehensive catalogue of all the problems he sees today in Indonesian society and the need for a stronger sense of nationalism. Some key themes of the book are environmental exploitation, foreign ownership of Indonesian assets and the neglect of human rights, including the rights of the poor.

From red to green

Harsutedjo explains that for him ‘loving one’s country means protecting and safeguarding the land and water that we own and all that grows and lives in it, all flora and fauna and all water and sea as well as the air above it and its people’ (p. 5). He expresses great regret that Indonesian leaders do not seem to value these things as evidenced by the 2002 ‘loss’ to Malaysia of the two islands of Sipadan and Ligitan at the border of East Kalimantan. According to him, the two islands were handed over because of a regime that ‘prioritised its own power and its own pockets’. More small islands have been and will continue to be lost and to sink because of ‘the greed of giant investors’. According to Harsutedjo ‘They collude with the regime to steadily steal the coral, the sand and to dig up the mangrove trees which have for thousands of years guarded and preserved our seas and our land’ (p. 5).

The illegal sale of timber, sand and soil at low prices to Singapore is evidence that Indonesians have already sold their homeland’ (p. 5). Throughout his dictionary Harsutedjo lists many other cases in which Indonesia’s economic sovereignty has been compromised such as through the sale of mining and oil concessions to foreigners. In our interview, Harsutedjo stated that ‘compared to the Sukarno era there is now more foreign exploitation, but also national exploitation’. He gives the example of the privatisation of water for use in rice fields and of drinking water.

|

The Dictionary of New Order CrimesKomunitas Bambu |

Harsutedjo’s contemporary critiques about economic exploitation mirror those made by many Indonesian nationalists in the 1950s and 1960s concerning the need for complete – including economic – independence. In the 1950s, the Indonesian economy continued to be dominated by Dutch companies. Many people were wary of allowing further concessions to foreign companies to exploit Indonesian resources such as oil. In an era of neoliberal globalisation such critiques have continuing resonance.

Harsutedjo documents throughout his dictionary the many human rights the New Order regime infringed, especially the rights of those imprisoned in relation to the Thirtieth of September Movement. The regime’s violations included not only imprisonment without trial, but also continuing stigmatisation once prisoners were released. Prisoners and their families were barred from certain occupations and they had to report regularly to local authorities.

Despite much talk of human rights since the fall of Suharto, for Harsutedjo human rights protection has not gone far enough: ‘the only people whose human rights are respected are the corruptors and those who have committed human rights abuses’ (p. 118). Referring to the string of violent episodes and massacres from the 1960s through to the late 1990s, he writes ‘A civilised country would not allow this tainted and bloodstained history to pass by without an investigation, such that the same thing may happen again’(p. 118).

Harsutedjo’s critiques mirror those of others of the Indonesian left who are still waiting to see some form of justice for the crimes of 1965-68. Despite investigations by both the National Commission of Human Rights and NGOs, time and again there has been no political will to prosecute those at the highest level of the military for these crimes. The military continues to enjoy impunity.

The triumph of capitalism?

In our interview, Harsutedjo commented that in the Sukarno era, ‘people used to be more idealistic, now they are pragmatic. No-one used to talk about becoming rich, now everyone does. It used to be a taboo.’ He notes that although the word capitalism still has some negative connotations, Indonesia now well and truly follows a capitalist system. He describes modern day Indonesian capitalism as ‘primitive’ because companies are able to pay off parliamentarians to pass laws that protect their interests. ‘New laws are passed that protect those who already have wealth, not the impoverished.’

In his dictionary he elaborates on this theme. ‘In the brutal form of capitalism that exists today in Indonesia the financial, chemical, pharmaceutical, automotive, tobacco, energy and other big industries hold the reins of the government in making decisions’ (p. 148). Meanwhile, many ordinary Indonesians do not have access to clean water, or cannot afford healthcare or education for their children.

No-one used to talk about becoming rich, now everyone does. It used to be a taboo

Harsutedjo is particularly scathing of the inequities that a capitalist system produces and the emphasis on private enterprise over public facilities. He writes ‘if we travel around the big cities of Indonesia, especially Jakarta we will see shops, huge malls, new offices and hotels being built, all competing to be the highest and most expensive building. When will we see the building of a new university complex, a public library and other facilities? Where is there a public library that is good enough?’ (pp. 252-53) Reflecting his background as a lecturer, he reminds his readers that education is the key to the development of a nation, yet Indonesia’s human development index remains low. It is ranked 107 out of 168 countries.

He laments the standards of Indonesian schools and the facilities they have. He blames this development on the New Order which ‘made education into an effective and massive instrument of selection, control and the socialisation of values, knowledge and skills so as to legitimate its power and to mobilise labour’ (p. 253.) This is the system that Indonesians have inherited from the old regime. Further to this, in 2008 the government passed laws to support the privatisation of education. He predicts that soon universities will erect signs saying ‘poor people are barred from entry’ (p. 254).

In the 1960s, the PKI founded people’s universities to encourage greater access to education, and there were more scholarships for poor students. Harsutedjo was one of those poorer students who received a scholarship, including a living allowance from the government. Thousands of trained teachers were killed or purged from schools as part of the anti-PKI pogrom in 1965-68. Harsutedjo notes they were rapidly replaced in the late 1960s with people with inadequate qualifications who would willingly implement the regime’s ‘new style’ education.

Looking forward

Harsutedjo has no immediate solutions to the conundrums of contemporary Indonesia. He would prefer tighter controls on foreign ownership and prevention of environmental destruction. He would like to see leaders protect the human rights of all Indonesians, especially the poor. The tone of nostalgia in many of Harsutejo’s recollections, of longing for a ‘purer’ past, is common to many survivors of the 1965-68 violence.

Yet Harsutedjo is more balanced than some in looking back on this past. He recognises, for example, that there was also corruption in the 1950s and 1960s and that it involved not only members of the military, but also some on the left. He is committed to an honest re-evaluation of Indonesian history.

In our interview, he commented that the young generation ‘must know Indonesian history what the PKI, Sukarno and Suharto were or they will not be able to evaluate why the contemporary situation is in such disarray and how we can move forward.’ In order to understand how Indonesia has gone so far in one direction, one must understand what kinds of ideas were discarded when the left was destroyed.

Katharine McGregor (k.mcgregor@unimelb.edu.au) is a historian of modern Indonesia and works at the University of Melbourne.