Kathryn Pentecost

Bruno BerlerPentecost Family Collection |

In 2009, my brother came across a reference to our grandfather (whom, in the Dutch tradition, we called opa) on the Verzetsmuseum website in a story about Dutch resistance member, Bep Stenger, the one survivor from the Corsica resistance group who had lived through incarceration by the Japanese. Our mother had often told us that only one woman had survived to tell the families about the fate of my opa and his colleagues, who were tortured and executed by the Japanese. The story on the Verzetsmuseum website was the very first time that I had seen Bruno Berler’s name in print and I was grateful for the sense of historical legitimacy that was now bestowed on one of the family ‘myths’. It was also exciting because so little is known about the role Jewish people played in the Japanese occupation and the Bersiap period.

Coming to the Indies

My mother often referred to her father, as a ‘remittance man’. Her explanation was that, after one unsuccessful business venture in Mexico, Bruno had returned home to Vienna, where his mother lived with her second husband, well-known Hungarian academic, later ambassador, Gyula Szekfu. The family then paid Bruno to go abroad again to make his fortune. This time he went to Java in the Netherlands Indies, where he made various forays into commercial ventures, mostly with untrustworthy business associates.

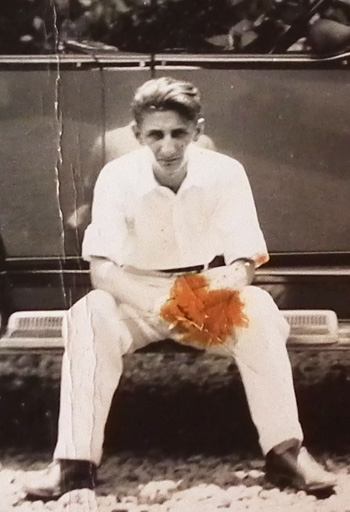

At the beginning of 1933, Bruno was photographed sitting on the running board of a new Chevrolet. Dressed all in white and wearing leather boots, he could have been any ‘respectable’ Dutch colonial, except that his hooked nose and his Viennese accent perhaps distinguished him from the VOC or other Dutch nationals. The car certainly gave the appearance of wealth and status. Bruno had been introduced to Riki, his fiancée, by a Dutch friend who was, at that time, married to Riki’s sister. Likely, my opa was trying to impress his future in-laws, who did not sanction the impending nuptials and, in fact, disinherited his future bride, because she had refused to marry someone more suitable. Later, that year, Bruno and Riki married despite her parents’ displeasure and the wedding photo, with Riki’s many siblings all dressed in white, is like a scene from a silent movie set – elegant and curiously quaint.

By the time of Bruno and Riki’s marriage, Hitler had manoeuvred himself into the Reichstag and the Nazis had become the only legal political party in Germany. Shortly after their first daughter’s birth in 1934, the German people had witnessed the Night of the Long Knives and Hitler had seized power. By the time their second daughter’s birth in late 1935, the Nuremberg Laws which institutionalised ‘race’ and the persecution of Jews, had been enacted. A full Jew was now defined as a person with three Jewish grandparents; others were classed as Mischlinge (mixed-race) – first or second degree, depending on whether one had two or one Jewish grandparent.

‘Race’ was also an issue in the Indies. Under the Tripartite Racial Policy, people of the Indies were classified into ‘European’, ‘Eurasian’ and ‘Foreign Oriental/Chinese’ by the Dutch colonisers – although most of those classified as ‘European’ by the late colonial period, were actually Indo-Europeans. In our family, Riki’s Javanese ancestry on her mother’s side was hidden by Dutch paternalism and the van der Poel family name, and earlier Muslim ancestry lay buried beneath layers of colonial Christianity. Bruno’s legacy added yet another layer of complexity to our ancestral melting pot, with its (mostly) Dutch and Javanese antecedents. Bruno was what might be termed a ‘secular’ Jew, whose German-Jewish family had forebears from Poland on his mother’s side.

Brush with death

Bruno’s entry into life in the Indies was not made at a particularly prosperous historical moment. But Bruno was an eloquently vociferous man, who spoke Dutch, German, Hungarian, English and three dialects of Indonesian. His outgoing nature certainly equipped him for being inventive and socially connected. However, it also drew him dangerously close to politics. His activism would land him in trouble in both Europe and the Indies and his own prognostications about his fate at the hands of the Japanese would tragically prove all too true in the years to come.

By the early 1930s, the Depression had left its mark on the Indies economy and Bruno’s young family was struggling. They were forced to move over twenty times all across Java, living in many different places, including Bandung, Surabaya, Malang, Jember, Puger and Bondowoso. Before the Japanese occupation, Riki’s parents had a fish-farm and export business in Puger, a small town on the far south-east coast. The Berlers had to return from time to time, when their financial situation became too precarious.

|

Bruno with his Chevrolet in 1933Pentecost Family Collection |

In 1938, Bruno decided to take his young family to visit relatives in Europe. The timing was inauspicious. On 12 March, German troops goose-stepped into Austria and three days later annexation was completed, with the passing of Austria’s first anti-Jewish laws. Bruno was overheard making negative remarks about Der Fuhrer and marched off to the recently renovated Dachau concentration camp in Bavaria. Although officially Dachau was not yet an extermination centre, Jews had been dying there since 1933.

Afraid that Bruno would die in Dachau, Bruno’s mother and step-father decided to bribe the Nazis. Bruno was only about 40 kilos in weight by the time he got out. After his release, Bruno, Riki and their two young daughters, fled to Genoa in Italy and managed to get on the last ship sailing for the Indies. They arrived home worse for wear, but enjoyed a few years of relative peace before Bruno joined a small resistance group in Malang after the Japanese forces occupied Java in March 1942.

Resistance fighter

Bruno joined the Corsica group, led by WA Meelhuysen (aka Tahir), a captain in the Dutch colonial army. The group was one of the first strongholds of resistance against the Japanese. Operating out of the Red Cross office in Malang, it engaged in guerrilla actions, espionage and sabotage as well as supporting resistance fighters in the mountains by sourcing clothing, medicines and weapons. It appears that the Dutch government directly funded the group.

Mum always told us that Bruno and one of his colleagues had greeted the Japanese officers sitting at their desks, with their feet up and wearing only their underwear. This deliberately impolite act was designed to buy them some time; Bruno believed that the Japanese would not kill them immediately in this situation.

|

The Berler family: Tony, Riki and Myra in 1949Pentecost Family Collection |

The popularity of the Japanese had quickly diminished among the Javanese because of raping and looting by the occupiers. But there was not enough support to make the resistance truly effective, and there were many informers willing to reveal the underground activities of those such as Meelhuysen. At the end of 1942, he was arrested, tortured and committed suicide in prison so as not to betray his compatriots. Bep Stenger, Ferry Pleyel and Bruno Berler, among others, were also arrested and tortured for many months. My mother recalls that she had to go to the prison gates to collect bloodied clothing and hand over fresh supplies and clothes for her father. She also told us that eventually the Japanese pretended to release the prisoners then shot each in the head as they were walking out the prison gates.

In 2009, my brother and I discovered that the truth was far more gruesome. After an official trial, ten death sentences were read out and all the men, including Bruno, were then beheaded by the Japanese on 31 January, 1944. Their bodies were taken to a mass grave at Antjol (near Jakarta) where his name still appears with his compatriots on a simple white grave marker.

Bruno Berler is just one man among many non-indigenous people who called the Indies home, and who died defending his adopted country from Japanese oppression. The Japanese may have promised to liberate the Indonesians from Dutch colonialism, but in the years to come, while glad of their independence, many Indonesians would still reflect on life under the Dutch as the Zaman Normal (normal period), in comparison to the cruelties, indignities and violence they had experienced at the hands of the Japanese.

Kathryn Pentecost (kathrynpentecost@hotmail.com) is a PhD candidate at The University of South Australia’s School of Communications, International Studies and Languages, Magill Campus, Adelaide. Her research focuses on her maternal family history in the Indies (et al), focussing on issues of racism and national identity under Dutch colonialism, during World War II Japanese occupation and emerging Indonesian nationalism.

This article is part of the Indonesia's Jews series.