The members of Tempo Dulu reminisce about Jewish life in Indonesia

Ayala Klemperer-Markman

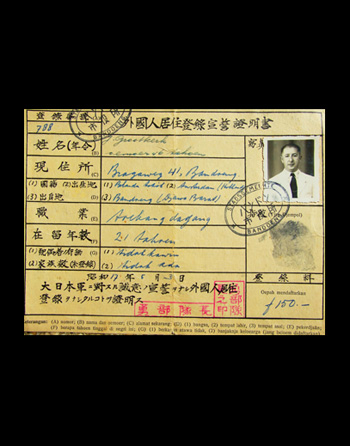

A wartime alien registration certificateHanoch Silberberg |

'I feel that God keeps me alive in order to tell the unknown story of the Jews of Indonesia,' says Regina Sassoon, aged 95 and still the lively centre of her family, and of the Tempo Dulu Foundation, a small organisation of Jews from Indonesia living in Israel. Having been starved and interned in camps during the Japanese Occupation (1942-1945), and almost butchered during the Bersiap period (August 1945-December 1946), she believes that she is still here with us solely for this purpose.

Sassoon was born in the Malaysian town of Penang in 1916. Her father, Moshe Sassoon, had fled Basra (now in Iraq, then a part of the Ottoman Empire) in 1910. Without a penny in his pocket, he managed to sneak as a stowaway onboard a boat bound to Burma. From there he travelled all over East Asia, until he met his wife in Penang. The couple settled down two years later in Surabaya, where they soon became one of the prominent Jewish families in the city. Following the Japanese occupation of Indonesia and the Bersiap period, the family emigrated to Israel. Today, from her living room in Kiryat Ono, Israel, Sassoon dedicates much of her time and energy to commemorate the story of her long-lost community.

Eating flies to survive

The membership of Tempo Dulu includes individuals from the three main groups of Jews in Indonesia on the eve of the Japanese occupation: those of European extraction, who had resided in the Dutch East Indies for years, some for generations; the so-called ‘Bagdhadis’, like the Sassoon family, who had emigrated mainly from the area known today as Iraq; and a much smaller group of recent arrivals who had fled Nazi Europe.

Born in Vienna in 1934, Suzzane (Suzi) Lehrer was the daughter of a well-off middle-class family, who had fled Austria to the Dutch East Indies in December 1938. Following the Dutch capitulation in March 1942, her father was arrested. At the time, she and her mother were hiding in a Christian convent. Not long after, they were ordered to present themselves at the Japanese headquarters. Lehrer recalls:

Our names were on a list of Jews to be transported to concentration camps. Someone must have snitched on us. We were ordered to go to the central train station, leaving behind practically all our possessions. Then the long journey started. We were loaded on trucks, all of us squashed together, women and children, standing up. We stopped at the gates of Tanah-Tinggi prison, where we saw the place that was going to be our ‘home’ for the next year or so … Until then this jail had been used only for Indonesian criminals, murderers and robbers. We were ushered through the gates, the sun burning our heads. As we were slowly processed, the Japanese soldiers ordered us to give them any money or jewellery we had. We were assigned a cell, two people to a cell. There was very thin mattress on the floor, and a tin was pressed in a corner for our toilet needs.

This cell was the Lehrers’ home for almost a year, until they were transferred to the Tangerang internment camp, west of Batavia (present-day Jakarta). In Tangerang, like in many other camps, men were interned separately from women and children, and Jewish women and children were kept separately from non-Jews. The women were separated from their husbands for the next three and a half years. Many of them never saw their husbands again.

Nothing was left of the things that had previously defined their comfortable lives as Europeans in the Dutch East Indies. They had lost all their belongings, their beautifully kept homes, their servants, many of their friends. Most had left for these camps with just a small bag of belongings, and some children to take care of. Each family was allocated one room, regardless of its size, whether a garage or a hallway, a veranda or a pantry. Sleeping arrangements were in most cases bedding on the floor, on cots, or on mats. The serving of meals was organised by designated inmates from the field kitchen. However, the meals were less than substantial, and could not satisfy the hunger of the inmates. Anyone caught smuggling in food suffered severe punishment, which might include a day under the Indonesian sun with no water or a month in a dungeon.

Born in Balikpapan in 1939 of a Dutch background, Renee Velleman was merely four years old when she was first interned together with her sick mother. They were transferred seven times from one camp to another, sometimes by foot, other times by freight train. During those transfers, they were given almost no food. Velleman recalls, ‘We became experts in catching flies – they served us as a source of protein. ‘They were regularly beaten and suffered tropical diseases. Some of those who could not keep up were executed. No wonder she refers to these transfers as 'the death marches of Indonesia'.

Joining the Europeans

In August 1943, the Bagdhadi Jews, who had been kept out of the camps until then, joined the Europeans in ‘protective custody’. Sassoon, by then the mother of four young children, recalls the moments when her life was shattered:

It was 4:00 o'clock in the morning when they came, with their big trucks. First they took the men, and then they came for the women and children. I had four children then. The youngest one, Thelma, was still a baby, and the oldest was about five and a half years old …We had no time to pack anything. Clothes we didn't have, shoes we didn't have, only what we were wearing.

Driven away from their homes at dawn, these men, women and children were first locked up in Surabaya's Werfstraat prison. 'Conditions in this jail … were very cruel. We were not treated like human beings. We hardly had any food. They would give us vegetables with the earth still in their roots. We had to wash it again, and then we would eat it like grass. And the rice – it had worms in it,’ Sassoon recalls. Many died in that jail. Some of malnutrition, others of lack of medicine.

After a year they, too, were transferred to camps near Batavia, first to Camp Tangerang and then to Camp ADEK, where the Bagdhadi Jews were held in separate barracks from European Jews, who were themselves in turn segregated from other Europeans. Some testimonies by survivors of the camps suggest that there was discrimination against Jews within these camps. These claims cannot be verified, and could be explained simply by an informal camp pecking order. But survivors claim that when the food was distributed from the commune kitchen, it was served first to gentiles and then to European Jews. It was only after this time that it reached the barracks of the Iraqi Jews. In such circumstances, it is hardly surprising that often very little food remained.

Still, it must be remembered that the fate of the Jews in the colony did not differ much from that of non-Jewish Europeans, who fared considerably better than native Indonesians. While about 30,000 Europeans died in Japanese concentration camps in the Dutch East Indies, possibly as many as four million Indonesians died during the Japanese occupation. In fact, what brought about the demise of the Jewish community was not the hardships of internment, but rather the revolution that followed – and especially the Bersiap period.

Navigating the chaos of the Bersiap period

Japan surrendered to the Allies on 15 August 1945 and Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta declared Indonesian independence two days after the Japanese capitulation. A period of chaos ensued in the final three months of 1945 and throughout 1946, as hundreds of local Indonesian combat groups armed with Japanese weapons operated with no central leadership. There were street fights and former Dutch internees outside the camps were systematically attacked and fired upon. Assaults, kidnapping and murder were commonplace.

The Bersiap period found Sassoon in ADEK camp in Batavia. Longing for some good food, she left the camp one day to buy some fish in the market. It was only then that she realised what was going on outside the camp:

Young people were approaching us, pointing at us with their bamboo spears. I knew that they could easily kill me. Then suddenly, luckily, I saw an older Arab man. He looked kind, so I approached him, begging: 'please, please protect me and take me to your house.' He talked to them. Then they stopped it. They were going to murder us. He saved my life. When we got to his house, I told him that I am from the Sassoon family, and he said that he knew my father. He asked me to stay in his home, as it was dangerous outside, but I had to go back to my children. So I turned the road near his home waving a white cloth and waiting for a ride, until a British tank stopped, and took me back to the camp. When we reached ADEK, people were so relieved.

When the internees could finally leave the camps, they started looking for their relatives and homes. Soon they found that their houses were occupied by other people, that many of their relatives died and that the revolution destroyed a colonial administration.

Longing for home

When the opportunity arose, most Europeans decided to leave Indonesia, and move to the Netherlands. Among them were the Lehrer and the Velleman families. But when they reached their destination, they did not feel at home. They had a different background from their neighbours because they had spent so many years in the Dutch East Indies. Eventually, Suzi Lehrer and Rennee Velleman moved on to Israel.

Most of the Baghdadi Jews initially stayed on in Java. Sassoon had five more children, who were all born in Surabaya. They felt integrated in the local community and they went to Indonesian schools. They studied wayang, were active in sports and traveled extensively in Java with school and family.

But the good times didn’t last. After the bloody events of 1965, the Sassoons felt compelled to leave, and they moved to Tel Aviv. But here too, it took them years to feel comfortable in their new surroundings. And they still feel most at home among their fellow members of the Tempo Dulu Foundation, with whom they meet, enjoying old Dutch movies, their traditional rijsttafel and especially their memories of a community long gone.

Ayala Klemperer-Markman (ayala.klemperer@mail.huji.ac.il) teaches Japanese history at Tel-Aviv University. Her research on the Jews of Indonesia was carried out as part of her post-doctoral work at the Department of Asian Studies in the University of Haifa, Israel.

This article is part of the Indonesia's Jews series.