Ronit Ricci

Wang Xiang Jun’s Menunda Munculnya Dajjal 2012Ronit Ricci |

Although the vast majority of Indonesians have never encountered a ‘real’ Jew, there is no shortage of images and interpretations of Jews and Judaism in Indonesia. A quick visit to any Indonesian bookstore provides evidence of Indonesians’ largely negative views of Judaism and its followers. There, books can be found replete with provocative cover images, most often of the Star of David but also of money, fire, and Muslim sacred sites like the Ka’aba and the al-Aqsa mosque appearing as if they are under threat. Other recurring motifs are the equation of Judaism with Zionism and a conflation of Judaism with other groups popularly considered mysterious or conspiratorial, most notably the Free Masons.

But despite the fact that such negative views are indeed widespread, a deeper look shows that the figure of the Jew has been, and remains, ambiguous. It also makes it clear that Jewish figures and their representations are not a new phenomenon that emerged with news of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict or the rise of the internet. Rather, such representations, in their diversity and ambiguity, have deep roots in Indonesian Muslim society.

Stories from afar

Jews and Judaism have constituted an ‘other’ for Muslim Indonesians over several centuries. The earliest images of Jews to circulate in Indonesia may be those appearing in the Qur’an. But Jews also feature in works that were translated or adapted from Arabic and Persian into Malay, Javanese, Acehnese and Sundanese. These include the tales known as hadis Israiliya, derived from Jewish (and sometimes Christian) traditions, which depict the lives of early prophets like Adam or Jonah and familiar episodes such as Moses’ struggle with Pharaoh. Such stories appear in traditional manuscript literature as well as in popular collections, which circulate widely and are easily available. These tales, which convey a generally positive image, refer to Banu Israil (the Children of Israel) rather than to Yahudi (the Jews). The connection between Banu Israil and the Yahudi is often ignored by, or simply unknown to, contemporary readers.

Jews as Yahudi probably appear most often and prominently in manuscripts depicting episodes of Islam’s early history including biographies of the Prophet Muhammad, his kin and companions, and tales of Islam’s heroic battles. Likely the most widely circulating story focusing on a Jewish protagonist in the Archipelago is the Book of One Thousand Questions, translated as Hikayat Seribu Masa’il in Malay and Serat Samud in Javanese. Composed in Arabic circa the tenth century and translated widely thereafter, this book depicts a question and answer dialogue between the Prophet Muhammad and a Jewish leader by the name of Abdullah Ibnu Salam who, along with his followers, subsequently converted to Islam. This story reached the Archipelago by the late seventeenth century if not earlier and was retold in several languages and genres. Although these tellings are diverse, reflecting different concerns and agendas, the Jew Ibnu Salam’s image is a consistently positive one, highlighting his wisdom and his expertise in the four scriptures: the Torah, Gospels, Psalms and Qur’an. Ibnu Salam is a worthy opponent to the Prophet: a great scholar, a yogi, an admired leader, and a man who was able to first question the Prophet – and, accepting his replies, realise that Islam is Truth.

The Jewish scripture, or Torah, possesses a special role in this narrative. In some tellings Ibnu Salam replies to the Jews’ doubts about the Prophet Muhammad by noting that the Prophet’s arrival was portended in the Jewish scripture and therefore Ibnu Salam must meet him in order to determine whether he is indeed the awaited one. The Torah is presented as the source from which both Ibnu Salam and the Prophet derive their authority and inspiration, with Ibnu Salam’s questions drawn from it and Muhammad’s replies justified by repeatedly referring to it.

An intriguing and unusual section appearing in an early eighteenth century Javanese manuscript conveys explicitly the beliefs and identity ascribed to the Jews by an anonymous Javanese author. To the Prophet’s questions ‘who are you?’ Ibnu Salam replies:

Yes my name is Samud

I am Ibnu Salam

Indeed I follow

The religion of the prophets of Israel

Of the descendents of Jacob

I am exalted

Granted an authority in reading

The Torah scripture

By Him who sent

The prophets bearing it [to] me

Indeed that which is followed by all Jews

And Christians

In this reply, the centrality of the Torah as the basis for the debate and competition between the two leaders is again emphasised, along with Ibnu Salam’s status as a worthy opponent of Muhammad.

A narrative that shares many of the themes of the Book of One Thousand Questions but diverges in its representation of the Jewish protagonist and in its interpretation of his personality and actions is the 1792 Javanese manuscript Serat Pandhita Raib, known in Malay as the Hikayat Pandita Raghib. In its more complex plot the Jewish Pandhita Raib, warrior and advisor to the king at the court of Kebar, persuades kings already converted to Islam to renounce their new faith. A letter from the Prophet summoning him to Islam is rejected, and battles are fought, leaving Muhammad and his companions at a loss. A letter then falls from the sky upon the Pandhita. Opening it, he finds the Islamic profession of faith inscribed in luminous letters. Aghast, he commands the erection of a fort surrounded by walls and moats around the letter, forbidding all to approach it. His own son is drawn to the letter and gains access to it, immediately feeling a deep longing for the Prophet. Pandhita Raib tries unsuccessfully to kill his son. The story ends with the son’s conversion and the Pandhita meeting with the Prophet and subsequently returning to God.

Pandhita Raib is depicted as a devious and cunning figure, able to lure leaders and kings away from Islam by virtue of his exceptional powers, reversing the process of conversion initiated by the Prophet. He speaks of Islam with disrespect, is confident of his strength and refuses to surrender, overcoming in battle some of Islam’s most heroic figures. He is depicted as brutal and aggressive but is also endowed with a special light and the demeanour of a saint. His Jewish identity is mentioned explicitly yet briefly and for the most part he is referred to as an infidel.

There are several shared themes in the Book of One Thousand Questions and Serat Pandhita Raib, yet their differential treatment of these themes highlights the ambiguous and ambivalent perspectives on Jews and Judaism taken by local authors writing in Malay and Javanese in the late eighteenth century. Both books portray important events during the Prophet’s lifetime, one emphasising conversion by dialogue and persuasion, the other the struggles of early Islam to establish itself in an often hostile environment. Both of these historical and hagiographical dimensions were imported into the literature of the Archipelago and Jewish protagonists are fundamental to both. Both texts portray Jewish men as important, powerful and charismatic leaders holding sway over their followers, with one Jewish leader leading towards Islam, while the other leads away from it. Whether their power lies in religious authority or magic and the supernatural both are portrayed as formidable opponents to the Prophet, highlighting the significance of his ultimate victory.

These and other stories continued circulating in manuscript form into the early twentieth century. These textual depictions of struggles over the acceptance of Islam and the different paths to conversion must have resonated within Javanese society, itself undergoing a gradual process of Islamisation. In other words, such texts call attention not only to how Jews were perceived and imagined in ‘traditional Java’ but also to how Javanese Muslims telling these stories understood their own community and history. The narrative of early Islam was told, in part, through emphasising the Jew as an ‘other’ against whom Muslims could be portrayed and their identity defined – in doing so, repeating the process that had already taken place in the Middle East.

An ongoing battle

In more recent years Indonesian images of Jews have been shaped by a different kind of literature. An important source for Indonesian Muslims has been the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which have been immensely popular since the 1990s. Various versions have appeared in Indonesian, based on editions published in Malaysia, Iran and elsewhere in the Middle East. Many of these books include summaries and commentaries which present the Protocols – which purport to record a Jewish conspiracy to take over the world – as factual. Especially influential has been Ahmad Shalabi’s Perbandingan Agama: Agama Yahudi (translated from Arabic), which describes the Protocols as Jewish scripture. Additional examples include Sulaiman’s 1990 Ayat-Ayat Setan Yahudi and Saidi and Ridyasmara’s 2006 Fakta dan Data Yahudi di Indonesia: Dulu dan Kini, among others.

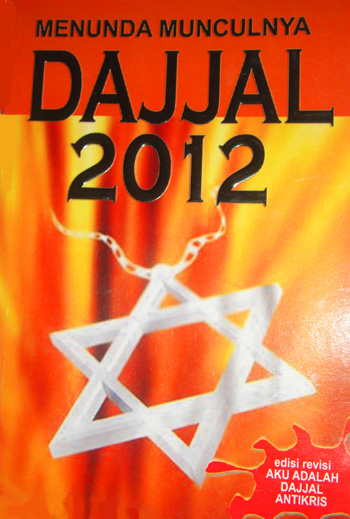

Similar themes are taken up in other kinds of books. Central among them include a Jewish threat to the world, Jewish conspiracy, Jewish wealth, Jewish power and the link between Judaism and apocalypse. Maulani’s Zionisme: Gerakan Menaklukkan Dunia sports a US dollar bill on its front cover, half covered by a blue Star of David, evoking the popular view that Jews control the world’s finances as well as the United States. Henri Nurdi’s Jejak Freemason dan Zionis di Indonesia (with an introduction by Abu Bakar Ba’asyir) shows the Freemasons’ symbol glowing enigmatically over a black background with the word Zionis printed in bold red letters, suggesting an intimate connection or even unity of the two movement. Wang Xiang Jun’s Menunda Munculnya Dajjal 2012 exhibits orange and yellow flames filling its cover with a large white Star of David dangling from a chain, equating Judaism with the coming of Dajjal, whose arrival signals the Final Judgment according to Islamic tradition.

But another form of writing, by moderate Indonesian Muslim intellectuals affiliated with interfaith organisations and Islamic universities, offers more nuanced and complex views. As Muhammad Ali has recently written, increasingly progressive views of Jews and Judaism in certain circles in post-Suharto Indonesia can be attributed to a desire for cross religious understanding and dialogue, supported by the government but often pioneered by non-governmental individuals and organisations. These writings mostly present authors’ understanding of the ‘Jews of Islam’ in Medina, Spain or Palestine rather than on an independent exploration of Jewish history. As a result, perceptions of Jews and Judaism depend on definitions of Islam and its history and textual traditions, reminiscent of the earlier trends of ‘reading’ Judaism through the lens of Muslim history and literature.

An unusually nuanced view of the Jews was advanced by the late Nurcholish Madjid, who considered Judaism as authentic as Islam and, importantly, stressed its inherent diversity. Nurcholish Madjid’s perspective called for an emphasis on similarities rather than differences across religions and saw the Jewish-Muslim co-existence of past centuries as a model that can equip Muslims today with the confidence that such conditions can be recreated.

Despite the many changes taking place from the days of manuscript copying in the eighteenth century to the present, then, two consistent, intertwined threads remain: an almost total absence of ‘real’ Jews from Indonesia, and the significant space their varied, often opposing, images occupy in the Indonesian Muslim imagination.

Ronit Ricci (ronit.ricci@anu.edu.au) is a lecturer at the College of Asia-Pacific at ANU. Her research interests include Javanese manuscript culture, Islamic literary traditions in Indonesia, south India and Sri Lanka, and translation studies. Ronit’s book, Islam Translated: Literature, Conversion, and the Arabic Cosmopolis of South and Southeast Asia, is forthcoming (2011) from the University of Chicago Press.

This article is part of the Indonesia's Jews series.