Abdul Chamid

Little escaped the volcano’s furyAbdul Chamid |

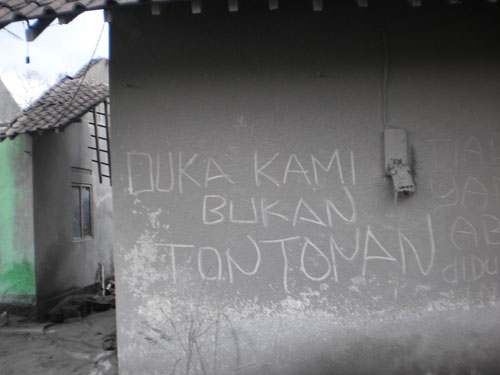

The devastation of the village, one of many in the sub-district of Cangkringan on the slopes of Mount Merapi, defies belief. All the familiar sights are gone – no more women carrying heavy loads of firewood, no more lines of ducks heading home across the rice fields, no children playing after school, joking with each other as they wash their buffaloes. All there is is silence, a total absence of life. The few houses not destroyed in the eruption lie derelict and abandoned. Dozens of motorbikes, reduced to nothing but scrap metal, litter the side of the road. In the middle of the village a tent has been erected over the villagers’ few remaining possessions, in an attempt to protect them from marauders. ‘We don’t know what to do, Pak. Why are people turning us into a tourist object?’ says a young man standing watch over the tent. ‘We don’t want outsiders here, gawking at the ruins of our lives. It makes us feel worthless and humiliated.’ His sentiment is echoed in a line of graffiti scrawled on an ash-stained wall nearby: ‘Our grief is not a sideshow’.

Surviving the aftermath

In fact most of the visitors to this scene of devastation are there to do what they can to help. They give willingly when asked for donations, sensing that the polite young men with donation boxes are not out to line their own pockets. They are part of a community effort to sustain the livelihoods of people still unable to work, in the wake of the massive volcanic eruptions that scarred the slopes of Mount Merapi and much of the Central Javanese countryside between 26 October and early December 2010. With all their animals dead and their rice fields destroyed, they are totally reliant on the emergency aid distributed through official evacuation centres. And emergency aid only goes so far.

Pak Wagiyono is one among hundreds of victims of the disaster. All that remains of his house is part of its timber framework and a couple of burnt out walls, now half buried in the flow of rocks and mud that descended on the village in the heavy rain that followed the clouds of hot volcanic ash. The well that used to provide him and his family with water is now submerged in the mud. The river Gendol, which used to flow through this village to a depth of 20 meters, past the shady trees that lined its banks, has disappeared without a trace. The gorge that cut a deep valley through the forest around the village has gone too, completely filled with sand and rubble. Three to four kilometres from the summit of Mt Merapi, this is what lava flowing at a speed of up to 300 kilometres per hour and at a temperature of up to 600 degrees centigrade leaves in its wake. The gathering darkness of evening is nothing compared to the darkness in the hearts of those who are left behind.

|

‘Our grief is not a sideshow’Abdul Chamid |

In another part of the village Pak Martorejo is trying to clear the ash from inside his house. A few buckets of water from a tank set up by the side of the road help him to uncover the remains of his tiled floor. Half of the house is gone and his furniture is all destroyed, but he counts himself as one of the lucky ones. His neighbours on both sides have nothing left that resembles a house at all. He and his neighbour across the street come every morning to press on with their work, even though the rest of the village remains deserted. ‘It’s better than just sitting there doing nothing in the evacuation centre,’ he says as he tosses a shovelful of ash onto the edge of the road. Each evening he returns to the camp to be with his family, who are still hesitant about coming back to the village. ‘It’s the trauma, Pak. It doesn’t feel right for my wife and kids, coming back here with no neighbours around them.’ At night it’s like being in the middle of the forest, no flickering lamplight in the distance, no sound of the nightwatchman’s radio. At this time of day, the villagers always used to listen to wayang broadcasts as they whiled away hours after a hard day’s work. ‘You won’t hear the sound of the gamelan here anymore,’ he sighs.

Strong convictions

Pak Martorejo is still undecided about whether to return to the village or sign up to a government relocation scheme. Like the other villagers, he’s reluctant to move away, despite the devastation, because this is where his ancestors have lived peacefully for generations. Up till now, this has been the land that has given them life, farming the soil and raising animals, or mining sand along the river banks. They have a strong spiritual connection to the land, with its fertile soils passed down to them by previous generations. It is a way of life deeply in tune with the Javanese traditions embodied in the wayang stories and the ancient sung poetry known as kidung. They live these traditions in their way of life, and pass them on assiduously to the young people of the village. Somehow, the vagaries of Merapi’s behaviour that vulcanologists find hard to predict, are still no match for their spirit.

It’s not that Merapi has not tried. Eruptions take place on average every four years, and as recently as 1996 thousands of people had their lived disrupted by its fury. The danger is always present, and it’s understandable if many outsiders see the villagers who inhabit the mountainous slopes as stubbornly indifferent to official calls for them to relocate. But the villagers themselves inhabit a different universe from that of modern science. Their traditions have taught them ways of living with Merapi and its moods, and up until the latest eruption they entrusted their safety to the spiritual gatekeeper of the mountain, Mbah Marijan. It was his ministrations, they believe, that saved them from disaster when Merapi seemed to be preparing for a major eruption in May 2006, just before the Yogyakarta earthquake.

|

Devastation on Merapi’s lower slopesAbdul Chamid |

In October 2010, Mbah Marijan ignored a call from the Sultan of Yogyakarta, Sultan Hamengkubuwono X, to leave his place of residence on the slopes of the volcano. The Sultan is both the modern-day Governor of the Yogyakarta Special Region and the age-old representative of spiritual power in the region, and in Mbah Marijan’s mind these were two separate realms of authority. To his way of thinking, the order to evacuate came from the government, through the sultan in his role as governor, whereas it was the sultan as traditional ruler who had appointed him gatekeeper of the mountain. Mbah Marijan chose to remain faithful to the task assigned to him by his traditional ruler, refusing to flee even when the danger was extreme. ‘What would people say if I were to leave now?’ he is reported to have said just before he died.

In the same spirit of faithfulness to traditional beliefs, the inhabitants of a number of villages in the district of Boyolali, on Merapi’s lower slopes, refused to follow evacuation orders without some supernatural sign that they should do so. What that sign might have been, and where it might have come from, is unclear, but the clash between traditional belief and scientific method often has a rational basis to it. In many outlying areas, there is no infrastructure to support disaster minimisation technology. Many villagers do not own radios or televisions, let alone mobile phones, and status alerts often fail to reach their destinations or do so only belatedly, because of conflicting and badly-coordinated reports from government officials. Villagers have no cause to trust scientific method, when it remains so divorced from the conditions of their everyday lives.

Rebuilding the future

Not long before he died, Mbah Marijan told a TV news reporter, ‘There’s nothing to worry about. Merapi is in the middle of a growth phase, that’s all.’ In the modern world, growth and destruction are often seen as opposites, but there was wisdom and insight in Mbah Marijan’s words. Merapi has wreaked death and devastation on a huge scale, but in a few years’ time, the massive deposits of volcanic matter the eruptions have left behind will have replenished the thin mountain soils, and opened up the possibility of future prosperity for the mountain’s inhabitants. Houses and infrastructure have to be rebuilt, and land has to be rehabilitated, all potential sources of employment opportunities and flow-on economic activity.

The question is, will the work of reconstruction be managed to bring maximum benefit to the survivors, now that the newsworthy moment has passed and the media has turned its attention elsewhere? The traumatised communities of the mountain slopes need food, shelter and medical supplies. But they also need long term commitment and long term thinking on the part of government and aid agencies, if the volatile mountain home of their ancestors is to go on sustaining life and livelihoods into the future.

Abdul Chamid (abdchamid@gmail.com) is a community development worker based in Solo, Central Java, and Selong, East Lombok.