A new generation of Indonesian theatre activists is staging performances based on the everyday experiences of local communities

Andy SW and Muhammad Abe

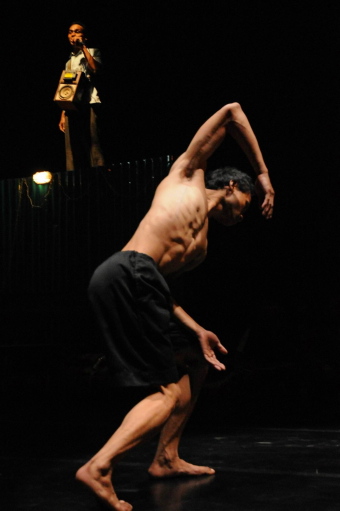

Scene from the play je.ja.l.an by theatre group Garasi.Mohamad Amin |

On 29 November 2009, a group of young performers from the central Javanese cities of Solo, Semarang and Yogyakarta met in the rehearsal space of the Bengkel Mime theatre in Yogyakarta. The gathering was small, but the issue was a challenging and important one: how to form a support network for small, independent theatre groups like themselves. Groups like those represented at the meeting share a commitment to socially relevant and artistically innovative theatrical performance; they also face the same problems in finding sources of funding and spaces to rehearse and perform. They were keen to hear about each other's experiences, to get fresh ideas and develop joint strategies.

One of those attending the Yogyakarta meeting was Afrizal Malna, a well-known theatre critic and poet. Not long after the event, Afrizal published a report in the national daily Kompas entitled 'A Meeting: Theatre of Death'. The report acknowledged the enthusiasm of the theatre groups represented at the gathering, but Afrizal claimed that in contemporary Indonesia theatre is dead, its life and energy taken over by performance art and new digital media. He cited the example of his friend, Boedi S. Otong, former director of the path-breaking 1990s theatre group Teater SAE. In recent years, Boedi has moved completely away from theatre to performance art. In Afrizal's view Indonesian theatre has lost the connection to society and ordinary people that it once had. He sees it as isolated from life, absorbed with technological innovation and consumerist values, a 'theatre of death'.

For those present at the meeting in Yogyakarta that night nothing could be further from the truth. Groups such as Roda Gila from Semarang, Teater EKS from Solo, and Seni Teku from Yogyakarta may be small, and their lack of any financial backing means they often perform in spaces like backyards and street stalls rather than theatre buildings. But this means they get to interact with ordinary people in everyday places, rather than just those who can afford to buy tickets and watch a performance in a hired venue.

|

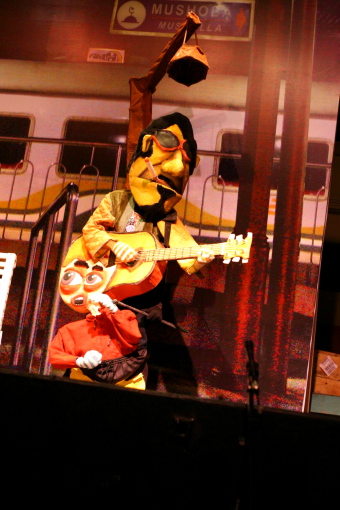

Cool dude in Paper Moon puppet theatre's production On a JourneyGemaliel W. Budiharga |

Groups like this are proof that Indonesian theatre is very much alive. They consist of young actors who believe they can influence society, and they have something to say to people. For them, theatre is a struggle to establish a place for themselves and their work, and they want to link up with other theatre activists to work out ways to advance this struggle. But why do these young people need to establish a new network, to start up something new? What has happened to the theatre networks of previous years?

Indonesian theatre after 1998

The fall of Suharto's New Order affected every aspect of Indonesian life. In the theatre world, the hallmarks of the long period of New Order authoritarianism had been a shared mission of political criticism and resistance to state oppression. After that era ended, many groups who had grown up in these conditions lost their focus and energy. A few of them kept going, but many abandoned theatre altogether, feeling that their work had no meaning in the new cultural context of reformasi.

But the period after 1998 was also marked by the appearance of many new groups, led by a younger generation, who were not attached to any political movement or viewpoint. These younger generation theatre activists look for new, fresh idioms that come from Indonesian daily life, new urban values and reinterpretations of village traditions in the contemporary context. They are active in various cities and regions, including Lampung (Teater Satu), Jakarta (PM Toh and Teater Syahid), Bandung (Mainteater), Solo (Komunitas Wayang Suket and Sahita, and Yogyakarta (Teater Garasi, Teater Gardanalla and Papermoon Puppet Theatre).

The theatre groups that have grown up since 1998 are richly varied in their approach. There is no one dominant idea about theatre form; each group has its own artistic idiom. They are also open to influences from other media. Some work with practitioners of visual art, music or digital technology, engaging with the cultural context of today. They also use their performances as a means to create new alternative spaces to build Indonesian cultural movements outside the mainstream culture created and controlled by government or global industry.

Their performances deal with themes taken from modern Indonesian history, as they try to present more subtle and complex perspectives than the confrontation with the state that characterised activist Indonesian theatre in the past

Performances after 1998 also represent the efforts of some theatre groups to create new forms of awareness in society. Their work raises issues of identity, gender, capitalism and religion, and deal with themes taken from modern Indonesian history, as they try to present more subtle and complex perspectives than the confrontation with the state that characterised activist Indonesian theatre in the past.

The group Garasi stages complex, sophisticated multi-layered performances reflecting on major issues in contemporary Indonesian society. Their production Waktu Batu (Stone Time), for example, combined figures from ancient Javanese myth with contemporary images to suggest the ongoing, problematic heritage of Javanese cultural tradition; Je.ja.l.an (Streets) depicted the confusion and lack of shared direction of modern Indonesian life through colourful, chaotic, conflict-ridden encounters between people on Indonesian streets.

Other groups stage simpler shows with a local focus. Slamet Gundono's Komunitas Wayang Suket, for example, criticises the booming construction of shopping malls in the city of Solo. Slamet, a shadow puppeteer, staged a wayang performance in front of a mall; he invited children to play games with him as part of the performance, to show how the attractions of the mall have replaced children's traditional games and threaten local cultural values.

Papermoon Puppet theatre uses human-sized puppets rather than real actors as performers. Each moved by a single actor, these puppets can walk, speak, express sadness, happiness, laugh, or even cry. Once the group brought their puppets to a traditional morning market and held a performance there. They asked the audience to help create a story about an old husband and wife who keep on selling vegetables in the market. Ria, the Papermoon director, explained that the performance was aimed at entertaining the traditional market visitors and seeing their response to this kind of event. Ria was surprised that many people laughed and enjoyed the show, and tried to interact with the puppets.

|

Family threatened by wild dog developers in Mak! Ana Asu Mlebu OmahAna Franz Surya |

Some other groups stage performances that connect in daring and innovative ways with their social context. Mak! Ana Asu Mlebu Omah (Mum! There's a Dog Coming into the House), a play written and directed by Andy SW about the real-life takeover of a Yogya neighbourhood by developers, was performed by local actors in the front yard of an old house in the very community where the events portrayed had taken place. Kintir (Drifted), written and directed by Ibed Suragana Yuga and performed by the group Seni Teku, mixes Javanese myth with modern everyday life. It depicts children deprived of their playground, who play on a dark and ghostly swamp until one of them falls and drifts away. His mother has already lost seven children in this way, like the goddess Gangga in a shadow puppet story from the Mahabharata epic, who gives up seven children to the river, then must farewell her last son, Bisma, as he leaves for the battle that will claim his life. The performance was staged in a village pendopo, an open pavilion traditionally used for shadow puppet performances, watched by an audience of villagers sitting around on mattresses.

A new theatre culture

All these groups are trying to build theatre culture in a contemporary context, creating their own language by writing new texts for their performances. More than their New Order predecessors, they are attuned to global cultural networks that are calling for openness and inclusiveness in social and political life as well as in performance art.

Far from being a 'theatre of death', as Afrizal suggested, they are breathing new life into Indonesian theatre and reconnecting it with the society from which it has evolved. The meeting last November did not solve their shared problems and challenges. But it did give rise to intensive debate on email discussion lists and plans for future meetings and joint performances.

Most importantly it strengthened their sense of participation in a dynamic and diverse new movement, their commitment to ongoing sharing of ideas and experiences, and their confidence that what they are doing is artistically exciting and socially worthwhile.

Andy SW (andysw80@yahoo.com) is the artistic director of Bengkel Mime Theatre.

Muhammad Abe (Muhammad.abe@gmail.com) is a theatre activist studying theatre at Gadjah Mada University.