Melissa Crouch

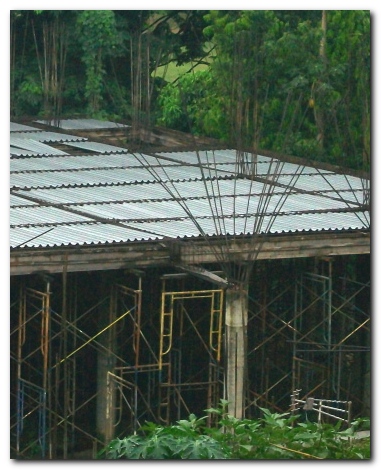

The construction of the church has been on holdSukron Hadi |

Places of worship are an extremely sensitive subject in contemporary Indonesia. Recent years have seen radical Islamic groups take the law into their own hands as they damage the places of worship of religious minorities, or force others to close by threats of violence. Local government leaders are also becoming more proactive against religious minorities, sometimes cancelling permits for places of worship that have already been granted. One of the first victims was the Christian Batak Protestant Congregation of Cinere, a town in the province of West Java. In May 2009, the mayor of Depok cancelled their permit to build a place of worship, despite the fact that construction of the building had already commenced. In response, the church asserted their democratic rights by filing a legal case in the Administrative Court of Bandung.

This case is significant for two main reasons. First, it is highly symbolic because the church belongs to the largest protestant denomination in Indonesia, with an estimated 3.5 million members across Indonesia. Second, this is one of the first court actions taken by a church against a mayor in relation to a dispute over a permit for a place of worship in Indonesia.

History of the dispute

On 13 June 1998, the mayor of Bogor granted the church a permit to build a place of worship. Four months later, the construction of the church commenced. Throughout 1999, however, large demonstrations by various radical Islamic groups such as the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) were held in opposition to the building of the church. In July 2000, the then mayor of Depok, Badrul Kamal, sent a letter to the church recommending that construction cease temporarily until the opposition died down. This effectively caused all construction works to grind to a halt until 2008, when the church decided to recommence building. The church wrote to the mayor of Depok, Nur Mahmudi Ismail, on three separate occasions asking for clarification of the validity of their permit and for protection. They had only completed the foundations and the first level of the building before their plans were again thwarted by demonstrations held in opposition to the church.

Then on 27 March 2009, with no prior warning to the church, the mayor issued a decision which cancelled the church’s original permit. Betty Sitorus, the current deputy chair of the church building committee, suspects that this decision was made to gain support for the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) in the 2010 local elections in the city of Depok. According to her, when the church questioned the mayor about his decision, he emphasised the fact that he made the decision as a Muslim and as a representative (and former chair) of PKS.

|

Local groups opposed to the building of the churchSukron Hadi |

The mayor’s decision was based on submissions from various government bodies and community groups, such as the Muslim Community Solidarity Forum, an Islamic group that claims to represent the aspirations of local Muslims in Depok. According to the forum head, they demanded that the church permit be revoked because it had acted unfairly by failing to comply with the Joint Regulation of 2006 on Places of Worship, which outlines the process to obtain a permit.

The mayor also relied on letters from the local branch of the Ministry of Religion and from the newly-established Inter-religious Harmony Forum, a body established by the reforms introduced by the 2006 joint regulation at the provincial and city/district level to facilitate the application process for permits for establishing places of worship and to assist in the prevention and resolution of disputes. In fact, the ministry’s brief letter simply recommended that it was the responsibility of the mayor to take action to resolve the conflict. Similarly, the Inter-religious Harmony Forum of Depok in fact did not suggest that the mayor cancel the existing permit, as explained by Dr Lodewijk Gultom, one of the forum’s two Protestant representatives. According to Gultom, the forum has been unable to prevent escalating tensions and, through a misinterpretation of its recommendation, was used by the mayor to legitimise his decision. This eventually led the church to take court action.

Resistance through the courts

The church, represented by its current national leader, Reverend Bonar Napitupulu, and the Cinere church pastor, Reverend Mori Sihombing, filed a lawsuit in the State Administrative Court of Bandung on 6 May 2009 challenging the decision of the mayor to cancel the building permit. Represented by lawyer Junimart, they argued that the church had obtained the permit legally and had fulfilled the conditions of both national and local building laws. They claimed that the mayor had no legal basis on which to cancel their permit, and that his decision was against the right to freedom of religion under Indonesia’s constitution. Junimart pointed out that the church had obtained the signatures of over 100 local residents as evidence of local support for the court – more than is required under Joint Regulation of 2006.

The mayor tells a different story. In responding to the church’s allegations, he referred to the changes that have taken place since decentralisation and the introduction of the joint regulation. He points out that the village of Cinere was only formed in 1999 as part of the process of decentralisation, and that the permit was obtained before this time. This means the head of the village of Cinere never had the opportunity to consider the application. Further, he argues that the original permit could no longer be valid because it was issued under an old regulation concerning places of worship that is no longer in operation.

However, Joint Regulation of 2006 confirms that permits issued prior to 2006 are still valid and legal. According to Fatmawati Djugo, lawyer for the Indonesian Christian Church of Bogor in a similar case in 2008, this provision clarifies that a place of worship which holds a permit under the old system does not need to obtain another permit. In addition, she emphasised that a mayor or district head does not have the power to cancel permits merely because there is opposition from the local community. A clear dispute resolution process is set out under the Joint Regulation. If there is dispute over a proposal for a place of worship, a meeting must first be held by the local community. If that fails to resolve the dispute, consultations are to be arranged with the local division of the Ministry of Religion and the local Inter-religious Harmony Forum. If that is not successful, the case can then be taken to court.

The Cinere case is among the first examples of a church congregation taking its case to court

In the Depok court case, the evidence was inconclusive at best. Both sides produced local Muslim residents as witnesses. Those for the plaintiff testified that they did not have any objections to the construction of the church, while the witnesses for the defence testified to the history of opposition to the church. Large crowds of people turned up in force at the court hearings demanding the closure of the church, many wearing clothes bearing the words ‘Front Pembela Islam’ (Islamic Defenders Front), the name of a radical Islamic group infamous for its use of violence.

After ten years of uncertainty, the court stepped in. On 29 October 2009, the court found that the church had obtained the permit legally under the old regulation and that the building fulfilled the requirements of national and local building laws. The court found that the church was not misusing the permit, which is the only ground on which a mayor could legitimately cancel a permit. On this basis, the court ruled in favour of the church. The mayor has since appealed the decision.

Regulating places of worship

As this incident suggests, local authorities continue to use conflict over places of worship as opportunities for political gain in the highly competitive political atmosphere that has developed since the downfall of Suharto in 1998. The church in Cinere is not the only example. The permit of the Indonesian Christian Church of Bogor was cancelled in 2008, as was the permit of the Santa Maria Catholic church of Purwakarta in October 2009. Both of these incidents occurred in the province of West Java, which has a high rate of church closures by radical Islamic groups. According to the Indonesian Christian Communication Forum, 70 of the 400 churches closed under the New Order (1966-98) occurred in West Java. In 2005 alone, the National Indonesian Communion of Churches recorded that about 50 churches were destroyed or forced to close in the province. Against this background, this case is notable because a religious minority turned to the legal process to assert their newly-found democratic rights. It is even more significant that they won the case.

Regulating the construction of places of worship and containing conflicts arising in the process remains a significant challenge for the national government. As these cases show, the Joint Regulation introduced in 2006 has largely failed to prevent attacks or closures on the places of worship of religious minorities. The outcome of the mayor’s appeal against the church in Cinere is a significant test case in this regard – even if the church is successful, the real issue is whether the court decision will have any effect in practice.

Melissa Crouch (m.crouch@unimelb.edu.au) is writing a PhD at the University of Melbourne’s Law School. She is a research assistant on Professor Tim Lindsey’s Federation Fellowship project, ‘Islam and Modernity’ in the same faculty.