Susy K Sebayang

Information provided to pregnant womenCourtesy of Summit Institute of Development |

If you have ever seen a woman in labour in rural Indonesia, you will understand the thin line between life and death. Despite continued efforts to reduce maternal and infant mortality, current estimates suggest that around 11,000 mothers die every year from pregnancy-related causes in the archipelago, along with 164,000 babies aged less than 12 months.

What can be done differently to prevent these deaths? Does it involve giving pregnant women more support? These were the questions we asked when implementing the Supplementation with Multiple Micronutrients Intervention Trial (SUMMIT), a large-scale medical intervention conducted in Lombok between 2001 and 2004 in an attempt to reduce the rate at which infants and mothers were dying on an island with one of the highest mortality rates in Indonesia. SUMMIT was part of a global initiative to obtain evidence of the benefits of multiple micronutrient consumption during pregnancy.

It is well known that women in developing countries lack not only iron and folic acid but also other micronutrients such as vitamin A, vitamin B, vitamin C and iodine in their diet - micronutrients that are important for the survival of their infants. The trial's main aim was to compare the effects of supplementing the diet of pregnant women with multiple micronutrients instead of following the existing government policy of only providing iron and folic acid. The supplements - a single capsule containing 15 micronutrients including iron and folic acid - were produced in Indonesia using a formula approved by the World Health Organisation. The results of the trial showed an almost 20 per cent reduction in infant deaths for women given the multiple micronutrients. This suggests that around 68,000 unnecessary infant deaths in Indonesia can be prevented every year just by providing multiple micronutrients.

Community care

In contrast to the conventional method of conducting trials, where the research team alone manages the interventions, SUMMIT was implemented through the government health system. Supplements were distributed through midwives, using the channels already in place for the distribution of iron and folic acid. The trial also involved community-based approaches to help support pregnant women, providing training for local villagers that equipped them to act as support persons for midwives and pregnant women.

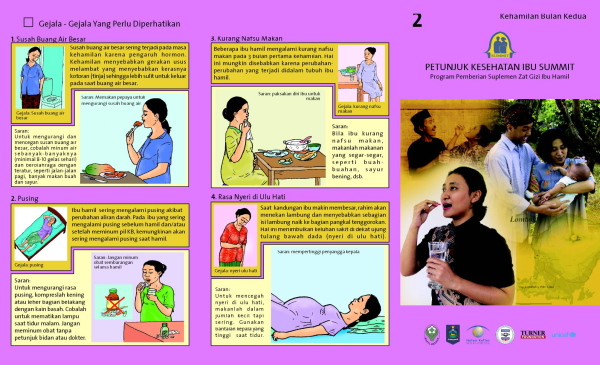

When visiting pregnant women, community facilitators reminded them to take their supplements, as well as discussing pregnancy-related health issues, including what commonly happens to the fetus and the mothers at various stages of the pregnancy. They also recommended nutritious, locally-available food. They answered questions from the pregnant women or their families, as well as giving information about scheduled activities for the closest local health centre, including prenatal and postnatal care. In order to address specific questions quickly, the community facilitators entered them into a data management system, allowing responses to be sent back from head office. They also provided administrative support to midwives and to volunteers at the local health centres during prenatal and postnatal visits.

In contrast to the conventional methods of conducting trials, SUMMIT was implemented through the government health system

Community facilitators helped make pregnancy care an educational and exciting experience. They hosted games during check-up sessions, in which women could win small prizes for correctly answering questions about pregnancy care. They also provided a SUMMIT birth certificate to women whose babies were weighed within one hour of delivery, thus promoting assisted delivery by trained professionals. This award was very popular, especially in villages where few deliveries took place at health facilities that could provide proof of birth. The SUMMIT birth certificate can be used as a supporting document when applying for a formal birth certificate. The community facilitators also found ways to increase community support for pregnant women from local leaders. Several Islamic religious leaders, who are very influential in the life of Lombok communities, spoke to men about pregnancy care at Friday prayers during the period of the trial.

Better outcomes

At the start of the trial most women went to traditional birth attendants when it was time for them to deliver their babies. But after contact with the community facilitators, women better understood the services that midwives could offer. Through this three-way collaboration, the number of assisted deliveries went from 36 per cent to 54.2 per cent during the trial. The risk of infant mortality was further reduced for women who both took the supplement and were assisted in their delivery by trained midwives, potentially saving at least 20,000 more babies every year.

It is not easy to recruit community facilitators, but by accepting local high school graduates without formal health education backgrounds, the trial reached 80 per cent of the population in Lombok. Through a strict recruitment process that emphasises motivation, intelligence, honesty and compassion, along with performance monitoring and evaluation, the newly-trained facilitators proved able to provide professional, up-to-date help to pregnant women. The local and national government have shown interest in the recruitment process, although different ways to make the role financially sustainable still needs to be explored. Wherever there are village midwives available the SUMMIT methodology can easily be replicated in Indonesia, and there are now plans to expand the initiative, empowering community facilitators to be village-based agents of change.

Susy K. Sebayang (ssebayang@health.usyd.edu.au) is a PhD candidate at the University of Sydney and member of the SUMMIT Institute of Development.

This article is part of our Health in Indonesia mini-series.