Lewis Mayo and Julian Millie

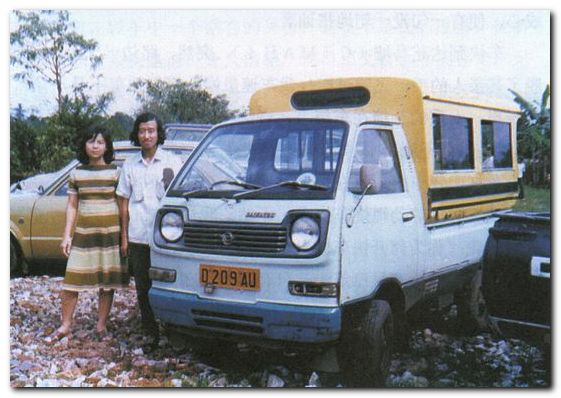

The published memoirs of Liong Tjie Tjong, seen here with his wife Kie Swie Tjwo, provide a rare account of lifeas a minibus driver during the New Order periodPhoto used with permission of Liong Tjie Tjong |

At the end of 1969 my father died of an illness, which forced me to shoulder life’s burdens and go out into the world. So I gave up writing and took up driving. I drove a minibus on the Bandung–Sumedang route, a round trip of over 90 kilometres….

These words begin the memoirs of the highly unusual life of Chinese Indonesian writer Liong Tjie Tjong. Liong – whose (Mandarin) Chinese name is Chen Zhizhang and who publishes in Chinese under the pen-name of Xiao Zhang – affords readers a highly personal insight into the effects of the New Order government’s discriminatory policies against ethnic Chinese. His writings provide a window into the inner world of Chinese-language writers in Indonesia during the years when they were denied opportunities to publish, following the closure of Chinese-medium schools and newspapers and the virtually total ban on the public use of written Chinese from 1966 onwards. They also give a unique picture of life under the New Order as it was experienced at street-level, from the perspective of a minibus driver.

Liong Tjie Tjong’s memoirs create a compelling and, at times, dismal picture of life as a minibus driver in and around Bandung in the 1970s

Born in Bandung in 1947, Liong Tjie Tjong was raised in a literary environment. His father wrote for the Jakarta Chinese-language newspaper Life News (Shenghuo bao), and the young Liong Tjie Tjong absorbed traditional Chinese literary models both through him and through contact with other senior Chinese-language writers active in the 1950s and 1960s. He studied Chinese at Ching Hua (Qinghua) Middle School on Bandung’s Jalan Cihampalas (now known to visitors as ‘Jeans Street’). In 1965, when he was finishing his secondary education at Hwa Chung (Zhonghua Zhongxue) in Jakarta, Liong Tjie Tjong had already decided to become a writer and translator.

The coup of 1965 thwarted these ambitions. In March 1966 anti-Chinese thugs invaded the Hwa Chung campus, stole the school’s equipment and burned all of the books from the school library. Then the army took over Hwa Chung, and Liong Tjie Tjong was forced to return to Bandung. In the years immediately following, the government issued a string of so-called “pro-assimilation” policies that effectively banned the use of the Chinese language, the performance of ‘Chinese’ religious observances and the use of Chinese-sounding names. Denied access to his chosen career as a writer in Chinese, Liong had to rethink his aspirations. The death of his father two years later increased the pressure on him to search for alternative ways of earning a living. As a result he entered the passenger transport business.

From writing to driving

Liong Tjie Tjong’s memoirs create a compelling and, at times, dismal picture of life as a minibus driver in and around Bandung in the 1970s. Along with the inherent economic insecurities of his trade and the risk of being robbed or assaulted, Liong faced demands for protection money from local underworld figures, constant requests for bribes from traffic police and harassment from military personnel. Liong depicts a life of constant vigilance, with the possibility that he might become the target of anti-Chinese violence always present in the background.

At the same time, he expresses appreciation of all people in Indonesian society who show a concern for justice and for the welfare of others. As well as the rare officials who did not seem to be using their positions for personal gain, these worthy individuals included passengers in his minibus who were willing to come to the aid of their fellows or to assist him in difficult situations. His many encounters during the period of military rule with violent, dishonest and greedy people, both in the government and outside it, did not dampen his faith in human goodness or his commitment to the moral ideals of the Sukarno period.

In 1979 Liong Tjie Tjong‘s life was to change once more. He went to the police headquarters in Bandung to renew his ‘A-general’ licence, the permit that authorised him to drive a minibus. To his surprise, the police official told him of the new rule: only Indonesian citizens could hold licences to drive public transport vehicles. Liong, though born in Indonesia, did not have Indonesian citizenship and was officially a citizen of China. Unable to renew his licence, he continued to drive illegally.

To his surprise, the police official told him of the new rule: only Indonesian citizens could hold licences to drive public transport vehicles

Liong’s status as an illegal driver required an even higher level of vigilance than before and left him in a state of constant agitation. He employed all kinds of tricks to avoid the police, relying on fellow drivers for news of locations at which police were checking documents, and developing the ‘long-distance vision’ required to see police officers before they could pull him over. If the police were checking drivers on his route, he would be obliged to stop and park for long periods, which meant that he would have fewer passengers. If caught by the police, he would have to bribe his way out of the situation.

In late 1981 however, the police eventually refused his offer to ‘show them a sign of his respect’ by means of a bribe. His minibus was confiscated, and he watched helplessly as the police siphoned the petrol out of all the vehicles they had impounded and then took it away in cans to be resold. Though an influential friend helped him to recover his vehicle and the police were prepared to offer him a month-long temporary licence, he realised that his driving days were over. Becoming a legal driver would require him to obtain Indonesian citizenship, and although it became possible in 1980 for Chinese people living in Indonesia to apply for citizenship, the process was expensive and could take as long as two years. The stress of continuing to drive illegally had become unbearable: Liong was facing increasing harassment from underworld figures and competition from newer types of minibuses. Buying a better vehicle was beyond his financial resources and his income was steadily declining. He therefore felt that he had no option other than to follow the recommendation of the police and change his profession.

Thus, 1982 saw the end of his career as a driver and he moved into small business activities: video rentals, dealing in automotive spare parts, working for a small company and, most recently, selling nuts and bolts.

Taking up the pen again

|

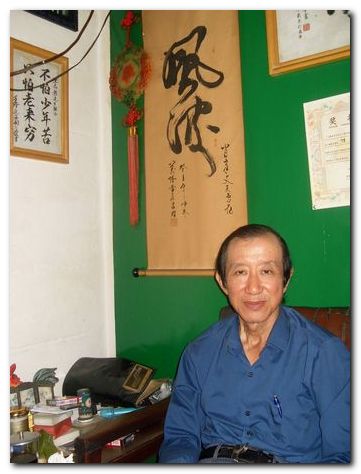

The events of 1966 forced Liong Tjie Tjong to alter his plans to become awriterJulian Millie |

In 2000, then President Abdurrahman Wahid repealed most of the laws that discriminated against ethnic Chinese Indonesians, including the restrictions on Chinese writing and publishing. Liong Tjie Tjong was finally able to deploy the literary skills which he had been prevented from using since 1966. He produced a series of essays, poems and stories in Chinese (first published in newspapers and then collected in his 2003 book Tempests) depicting his experiences before, during and after the New Order. Today he is active in the Bandung Chinese-Indonesian Writers Association.

His reflections on the past are coloured by a deep sense of loss. At the time when Liong was starting out as a writer, the Bandung Chinese community had enjoyed a thriving literary scene, but the New Order government forced it into inactivity. The effects of this have been demoralising. While Chinese culture was ‘in suspension’ for thirty years, generations of ethnic Chinese Indonesians grew up without access to the Chinese-language education that had been available before 1965 and which Liong himself values so highly. Today, Chinese youth in Bandung follow a Chinese-language study program that is, in Liong’s opinion, inadequate. Furthermore, the audience for writers such as himself consists only of people over the age of fifty. Younger people have neither an interest in nor the skills for engaging with writings of this kind.

Ironically, the very events that destroyed Liong’s literary aspirations have provided him with the material to draw upon in his second life as a writer. The resulting story is an unusual one. The prime of his life coincided with a regime that effectively put that life into disarray. Now, his literary skills give testimony to the everyday realities of life for Chinese people under the New Order, and to the persistence of the dreams of a better Indonesia and a better world that were so powerful in the 1950s and 1960s

.Lewis Mayo (lmayo@unimelb.edu.au) is a lecturer in the Chinese program of the Asia Institute, Melbourne University.

Julian Millie (julian.millie@arts.monash.edu.au) is a researcher in the School of Political and Social Inquiry, Monash University.

Gratitude is expressed to Liong Tjie Tjong for sharing his experiences with the authors. His recent book, published in 2003 under the pseudonym Xiao Zhang, is entitled Fengbo (Tempests). It is published by the Yinhua Zuoxie/Perhimpunan Penulis Tionghua Indonesia/Chinese Writers Association.