Hilmar Farid

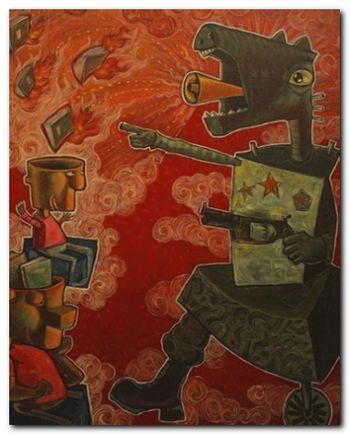

Artists rally against censorshipArip (Semurjengkol) |

In December 2009, the office of the Attorney General announced a ban on five books considered to be ‘disturbing public order’, among them a book by John Roosa entitled Dalih Pembunuhan Massal: Gerakan 30 September dan Kudeta Soeharto (A Pretext for Mass Murder: the 30th September Movement and the Suharto Coup). The ban came as a surprise, because the book, an Indonesian translation of the English original, was published two years previously and was already in wide circulation in Indonesia. In his directive, the Attorney General required anyone in possession of these books or holding them for sale to hand them over to his office.

The ban on the Indonesian translation of Roosa’s book is the latest in a long series of bans imposed for similar reasons.In fact, this was just one of more than ten bans on the distribution of books issued by the office of the Attorney General issued since reformasi.

In the early years after the fall of the Suharto regime, the press and book publishers seemed to enjoy a situation of total freedom. People were free to publish and discuss books that previously had been taboo, such as translations of the works of Marx, Engels and Lenin, and critical analyses of the 30 September Movement, the group that claimed responsibility for the attempted coup that led to Suharto’s rise to power in late 1965. More recently, however, the authorities have taken an increasingly hard line on books dealing with the events of 1965. In 2007, the same office responsible for the recent bannings had organised a dramatic book burning to destroy copies of a history textbook. The textbook in question was considered a danger because it omitted the ‘PKI’ that links the Communist Party to the 1965 coup in the New Order abbreviation for the 30 September Movement, ‘G-30-S/PKI’.

But it has been these most recent prohibitions that have provoked widespread anger. As the writers and publishers of the five banned books declared in statements issued soon after the Attorney General’s directive, the banning of books not only inhibits a citizen’s right to freedom of expression, but also the freedom to obtain information, which is guaranteed by the Indonesian constitution.

Maintaining order

The history of book banning in Indonesia dates back to the colonial period. However the present law, which gives the Attorney General the power to ban books regarded as ‘disturbing public order’, dates from a presidential decree of 1963 which was made into law in 1969, symbolically bridging the Sukarno and Suharto presidencies. In the New Order period this law was used to ban hundreds of books that were seen as threatening stability. It was even reinforced by a further – and unnecessary – law drawn up on similar lines in 1991. After the fall of Suharto, parliament overturned a number of laws regarded as inconsistent with the spirit of reform, but for some reason these two laws governing the banning of books seem to have escaped the attention of the lawmakers. For some years they lay dormant in Indonesia’s legal code, but in 2004, the parliament approved a new law that replaced the Attorney General’s authority to ‘ban’ books with the responsibility to ‘supervise’ the circulation of printed materials. Suddenly the old regulation of 1963, which legal observers and human rights campaigners had regarded as effectively obsolete, was now back on the agenda of Indonesian law enforcement agencies. The New Order mantra ‘public order’ (ketertiban umum) was back in currency, overriding the reform keyword, ‘freedom’ (kebebasan).

|

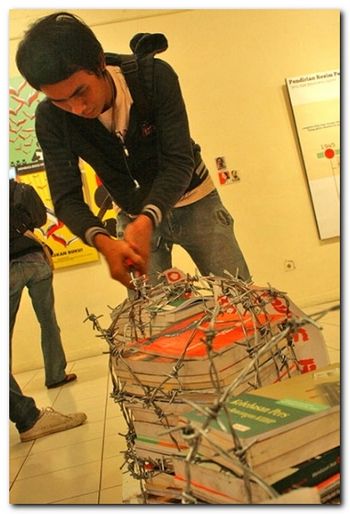

Cutting the chains that bindArip (Semurjengkol) |

The office of the Attorney General justified the new law by pointing to an amendment to the 1945 Constitution that permitted restrictions on constitutional rights in certain circumstances, including when people exercise their freedom in such a way as to limit the rights of other citizens or to endanger public order. In other parts of the world this issue has provoked debate, with some arguing that the right to freedom of expression must be absolute and that a mature society should be allowed to distinguish for itself between information and propaganda and truth and falsehood. Some however argue that restrictions are necessary to protect the freedom of others, pointing to restrictions on neo-Nazi campaigns in Europe, as such campaigns pose a threat to the rights and freedoms of other citizens. In Indonesia, this debate has barely begun and, rather than being the subject of public discussions, decisions on these matters remain entirely in the hands of state officials.

When the Attorney General’s office uses the term ‘public order’, it never explains specifically what it means. At most, a spokesperson will declare that a book has been banned because it contradicts what the government regards as the ‘truth’, such as in the case of the obligatory ‘PKI’ addition to the abbreviation ‘G-30-S’. In this case, there is an assumption that any departure from the official version of events – and thus the truth – must involve a threat to public order.

However the concept of ‘public order’ is in itself legally vague, and its definition is highly context-specific. A definition of what constitutes ‘disturbing order’ in a school cannot be used at a rock concert, for example. In my 20 years’ involvement in writing and discussing history in Indonesia, I cannot think of any book that has undermined public order. There have been a couple of controversial books that have upset some people or led to prolonged debate. But as far as I can remember, in all this time no one ever been killed or seriously injured because of a book. There have never been mass riots or attacks on homes and shops, let alone destruction of places of worship. It has only been the institutions of the state that have been ‘disturbed’, along with those – in the case of history books – who feel a need to defend their role in the events the book describes. That’s as far as it has ever gone. So where is the ‘public’ in this disturbance of ‘order’?

A lack of self-confidence?

|

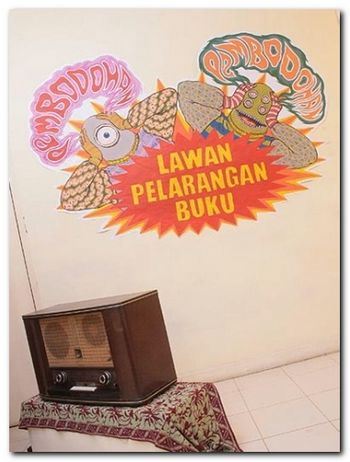

'Oppose Book Banning'Arip (Semurjengkol) |

Recently, it has not only been writers and publishers of books who have expressed concern about the resurfacing of New Order policies of censorship and control. Leading figures in both the press and the film industry have experienced a tightening of state supervision of media expression, and managers of internet sites and the blogger community have been protesting as well. Their concerns relate to a statement by the Minister of Communication and Information Technology that indicated a desire to place greater controls on the content of internet sites. Some of these protests have followed the legal option, like a move by authors and publishers to appeal to the Constitutional Court for abolition of the 1963 law on censorship on the grounds that it is in breach of the constitution. Others have taken to the streets, as happened in the case of the mass protests against restrictive laws on the film industry and the anti-pornography laws. As I write this, protests against the statement by the Minister of Communication and Information Technology are ongoing.

Amid the efforts to prevent a return to the New Order culture of censorship, one question keeps resurfacing: why should a government elected by the majority of the people feel so afraid of freedom of expression that it engages in book banning and even the public burning of books? The frequently-heard reply to this question is that the powerholders lack self-confidence. But if this is the case, why should the public be the victims? The lack of self-confidence on the part of the authorities has nothing to do with the public, even if it is this insecurity that leads officials to believe that they know what is best for everyone, rather than allowing citizens to determine this for themselves.

The citizens of a democracy are subjects, not objects, capable of determining what is best for themselves. It is this principle that must underpin the Indonesian legal system in the future, a recognition that the only justification for restrictions on freedom is when the freedom of some citizens may result in infringements of the rights of others.

Hilmar Farid (hilmarfarid@gmail.com) is a writer and historian based in Jakarta who is currently undertaking postgraduate studies at the National University of Singapore. The photographs accompanying this article were taken at an exhibition at the Jakarta Arts Centre in March 2010.