Jusuf Wanandi

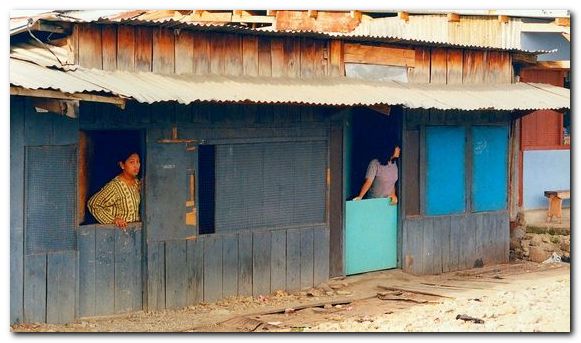

Signs of trouble: Indonesian shopkeepers board up their stores at the first sign of trouble in a highlands townGeoff Mulherin |

The Papuan dilemma all began with the Round Table Conference at the Hague in 1949, held to formally negotiate the transfer of sovereignty of the former Netherlands Indies colony to Indonesia. The Dutch Government, led by the Catholic and Protestant parties, did not want to recognise West New Guinea (West Irian) as part of ‘the Netherland Indies’, and wanted to exclude it from the newly independent Federal Republic of Indonesia. Indonesians knew it had long been part of the Netherlands Indies and wanted complete independence for all of Indonesia, including West Irian.

At the conference the Dutch Government forced an interim solution that postponed the decision on West New Guinea. Negotiations on the status of that territory were to be conducted over the 12 months following the transfer of sovereignty of the Netherlands Indies to Indonesia, and were to be concluded by the end of 1950. However, these negotiations were never approached sincerely by the Dutch, who wished to retain the territory in order to support the missionary purposes of the Protestant and Catholic churches there. After 12 months, no agreement was reached.

A frustrating decade

For the next 10 years, through international diplomacy, Indonesia tried to have the Papuan matter resolved. Finally, after a decade of trying, and becoming increasingly unhappy with the Netherlands’ neo-colonialist policies in West Irian, President Sukarno’s patience ran out. On 19 December 1961 he proclaimed his now-famous ‘Triple People’s Command’ (Trikora), mobilising the Indonesian state and people to regain West Irian by whatever means necessary.

This Trikora command was followed quickly by the creation in early 1962 of the new ‘Mandala’ military command, headed by Major General Suharto and based in Ujung Pandang (Makassar). Suharto began preparing for an all-out military attack into West Irian involving over 250 ships and about 100,000 armed service personnel and civilian volunteers.

The worsening diplomatic situation, and the growing prospect of armed conflict over West Irian, concerned the United States Administration. President John F. Kennedy did not want greater instability or more leftist extremism in Indonesia than already existed – real possibilities if armed conflict occurred. To circumvent this he sent his brother, US Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to Indonesia to persuade Sukarno to continue to seek a negotiated settlement. Sukarno agreed, and new talks between the Netherlands and Indonesia were held in spring of 1962, under the auspices of the United Nations (UN) and mediated by US diplomat Ellsworth Bunker. The talks were eventually successful and an agreement between the Netherlands and Indonesia was signed in mid-August 1962.

Agreement and transition

It was this 1962 ‘New York Agreement’ that returned West Irian to Indonesia. On 1 October 1962 the UN sent a team to administer West Irian for what would be only seven months before the transfer of the territory to Indonesian control in May 1963. The agreement also provided that after a period of six years of temporary Indonesian sovereignty an ‘Act of Free Choice’ would be held to determine the future of the territory. Following President Sukarno’s impeachment at a plenary session of the Provisional People’s Consultative Assembly (MPRS), General Suharto was elected as acting president in February 1967, and immediately began consolidating his government. The question of the Act of Free Choice was an unsettled problem he had to face. It was politically impossible for him as the president to lose West Irian; after all, he had returned the territory to Indonesia just a few years earlier as the Mandala Commander, carrying out Sukarno’s Trikora.

In early 1967 Suharto appointed Ali Moertopo, a senior military officer and Suharto’s personal assistant who had been with him during the Mandala Command period, to take charge of the developing situation in West Irian and to prepare for the implementation of the Act of Free Choice in 1969. At that time I had just joined Ali Moertopo’s staff. ‘Pak Ali’ asked me to join him on the Papuan mission instead of going back to a university career, or to the Supreme Advisory Council’s secretariat where I had been working before joining the anti-Gestapu/PKI (anti-communist) movement on October 1, 1965.

In early May 1967 I travelled with a team to investigate conditions in West Irian and returned with shocking but not unexpected news. West Irian had been completely neglected since it was returned to Indonesia in early 1963, due to the unfolding national crisis in Jakarta. The economic situation was very bad and the Papuan people there were not at all happy with the Jakarta government. Our first priorities, then, were to rehabilitate the economic well-being in the province and to assist the Papuan leaders to do their job, before the situation became impossible.

It was politically impossible for Suharto as president to lose Irian Jaya…

I proposed that we establish something along the lines of a domestic ‘peace corps’ in order to begin immediately improving conditions, and in doing so win some trust back from the Papuans. I obtained Pak Ali’s support to send over 250 students in July and August 1967 to work in every district across West Irian. The students distributed important goods, many of which were imported from Singapore, because as a result of the national crisis at that time Indonesia just did not have what was needed to supply West Irian. They built prefabricated housing in several districts and kept the airplanes flying – the essential transport asset even today across the province. But above all else they were friendly and helpful to the people and won their hearts for Indonesia.

Ali Moertopo was brave and brilliant as he met the challenge of funding West Irian’s economic rehabilitation. Recognising that at the time the Indonesian government lacked sufficient funds to meet the needs of the province, Ali Moertopo gained President Suharto’s consent to use the money Indonesia had in Malaysian and Singaporean accounts, the proceeds from the exports of Indonesian goods smuggled during the recent Confrontation with Malaysia. These accounts amounted to around US$ 17 million– a sizeable sum at that time. After two years of hard work some semblance of an economy was created in West Irian, and, importantly, attention was now given to the local people. Gradually Pak Ali’s team won some sympathy for Indonesia among the local people.

United Nations involvement

During this whole period of transition from 1963, Indonesia was always assisted by the United Nations (UN), through the Special Envoy of the Secretary General, Ambassador Ortis-Sanz. He was involved in the planning for the implementation of the Act of Free Choice, and agreed that the act could not be conducted using a ‘one man one vote’ system because the social-political situation across the province was not sufficiently developed for that possibility. It was agreed, therefore, that the Act could only be conducted using an indirect system involving local leaders selected through traditional ways. In the end a council of 1025 people representing every district took part in the Act of Free Choice in July and August of 1969, and decided to remain part of Indonesia. It was implemented under the auspices of Ambassador Ortis-Sanz and his staff.

In late 1969, the results of the Act of Free Choice were debated and voted upon in the UN General Assembly, during which Indonesia was supported by a good majority of the UN member states. Thus in accordance with the New York Agreement, the Act of Free Choice, and supported by the United Nations, West Irian remained part of Indonesia.

West Irian under the New Order

During the New Order era, which began with the change of name of the province from West Irian to Irian Jaya, the province was managed as were other parts of Indonesia. The unitary state was supreme, and local customs and traditions were ignored. Transmigration policies implemented by Jakarta were insensitive to local conditions and created social tensions. Unfortunately these policies continued right through until the end of the Suharto regime in 1998.

The real problem was the lack of human resources, both in terms of officials from the central government with responsibility in Jayapura (the capital of Irian Jaya), and because there were too few local leaders. Instead of being given priority, the region was neglected by Jakarta, and as a result the people suffered. The irony is that despite their resentment towards Jakarta, the tribal divisions and relative demographic isolation of many Papuans meant that the local people could not easily organise themselves, even to effectively struggle for their independence. And tragically, too often their leaders, already limited in numbers and in education, followed the Jakarta way of doing things, including engaging in corrupt practices and neglecting real development.

Reform and the future

While political reforms have been pursued in the post-Suharto democratic era, and cultural diversity has been recognised through special autonomy legislation, the establishment of the Papuan Council and the further name change to ‘Papua’, the problems persist. There remain insufficient well-educated and effective local leaders, and Jakarta seems not to send the best people to a region such as Papua that is really difficult to manage. And so Papua remains behind other provinces in development, and education, health, and infra-structure in particular are wholly inadequate.

Under the special autonomy provisions, the special subsidies granted to the territory will exist for another 17-18 years. Unfortunately, to date these subsidies have not been used as they should, and instead have been squandered by the local leaders for buildings, junkets and general corruption - all seemingly with the consent of Jakarta. Problems will loom large in the future if no major improvements are made and made soon. Papua is important to Indonesians, because of its history as part of the Netherlands Indies, because of the way we had to struggle to have it returned from the Dutch, and because of its resources. These resources should not again be plundered, but should be used wisely for the nation’s future development. This only reinforces the point that Jakarta must give greater attention and care to Papua. And the international community should be ready, willing and able to support the development of this region.

Looking back, the ‘event to remember’ for Indonesia was 1963 when the UN returned the sovereignty of Irian Jaya to Indonesia. We must not squander this opportunity.

Jusuf Wanandi (stanis@csis.or.id) is the Vice Chair of the Board of Trustees of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Foundation in Jakarta.

This article is part of our series on the fortieth anniversary of the Act of Free Choice.