Kelli A. Swazey

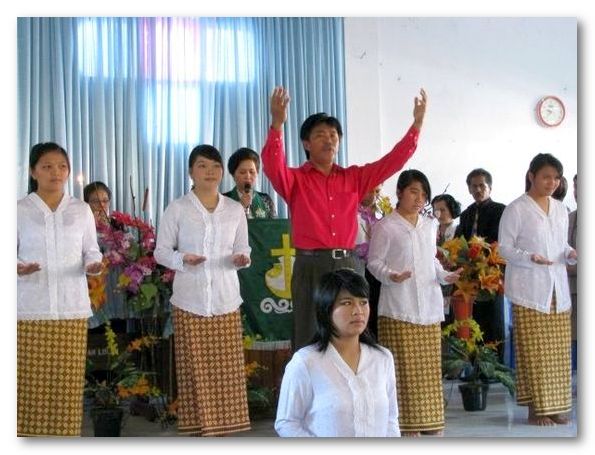

Members of the cultural committee perform a contextual liturgy in Tombulu during Sunday service at

|

The waxing moon takes central position in the sky above us as the calendar turns to 7 July 2009 in Minahasa, North Sulawesi. An eerie chant cuts through the chatter of the musicians who have been jocularly testing each other’s knowledge of local songs played on the guitar, tambour and ‘ting-ting’, a small metal xylophone. Pastor Paul Richard Renwarin from the local Catholic seminary school stands facing a crowd of thirty or so attendees as he inaugurates the evening’s multi-denominational Christian service with sounds drawn from the Minahasan past.

For many in the hushed crowd, the Tombulu language he uses is familiar, and for some a mother tongue. Although the language is old, the concept behind this service marks the beginnings of a new kind of Christian practice. Instead of standard Catholic liturgy, the focal point for this service is a section of a traditional poem relating the mythical origins of the Minahasan people. Described by the pastor as a local version of the Biblical creation story found in Genesis, the verses have been set to new music and are delivered in the call-and-response style familiar to anyone who has ever attended a Catholic mass.

This is the third year that a mixed group of Protestants and Catholics has gathered to participate in a midnight worship service at Watu Pinewetengan, the stone of division. As the central physical representation of local identity, this large, pictograph-covered stone located in the heart of Minahasa is said to record the division of the region into separate tribal groups during the pre-Christian era. Today, those tribal borders are roughly analogous to the surviving language groups in North Sulawesi. This tangible symbol of divided parts united in one unshakable whole is a fitting representation of both the people and the land called Minahasa, a name that means ‘to unite’ or ‘to become one’.

Protestant Christianity is one cultural commonality that the majority of Minahasans share, whether their first language is Tombulu, Tonsea or Tondano. Almost 90 per cent of the colonial region of Minahasa had converted to Christianity by the late seventeenth century, and contemporary Christian practices are as much a part of local tradition as more recognisable aspects of pre-colonial life such as dances used to celebrate the annual harvest. The line between religion and tradition is not easily defined in a region where Christianity has been part of everyday life for well over 100 years, and is complicated by historical rivalries between denominations that have different approaches to the inclusion of traditional practice in the church environment.

Including tradition

The Catholic Church in Indonesia has historically been more open to including traditional dances and other ritual practices as part of regular worship. In Minahasa Catholicism has played an important role in the preservation of ritual knowledge that was deemed inappropriate and subsequently suppressed by Protestant missionaries. Collaboration between the two denominations has been limited since colonial-era restrictions on Catholic missionaries sparked discord between Catholics and Protestants in the late nineteenth century. However, a new spirit of ecumenism is emerging between the region’s two oldest religious identities. Driven in part by changing ethnic and religious demographics that throw the link between Christianity and Minahasan identity into question, greater cooperation between Catholics and Protestants is also a result of inter-denominational competition and the growing popularity of newer Christian denominations such as the Pentecostal and Seventh Day Adventist Churches.

The appropriateness and meaning of traditional practices has long been a subject of debate among members of the largest Christian denomination in the region

Today in this northernmost province of Sulawesi, the process of deciding how pre-Christian practices and beliefs should fit within the lives of Christian people is an important aspect of the continuing definition of what it means to be Minahasan.

Questions about the appropriateness and meaning of traditional practices for Christians have long been a subject of debate for members of the largest Christian denomination in the region, the Evangelical Church of Minahasa (Gereja Masehi Injili di Minahasa, GMIM).

Over 800 GMIM churches in Minahasa are part of a standardised system, with everything from the salary of religious clergy to the contents of the hymnal book dictated by a central authority. This has left less room for GMIM members to use the church as a vehicle to preserve the various pre-Christian practices that continue to define who they are at the village level. However, decentralisation policies have changed the face of politics in North Sulawesi, creating an opening for public discussion and debate about local identity. As important centres of social life that are intimately connected to the flow of local politics, GMIM churches are also drawn into new discussions about what constitutes regional identity and what it means to be Minahasan in Indonesia today.

Rediscovering the past

|

Dancers from Rurukan, a village practicing contextual liturgy, perform the Maengket harvest dance

|

A small but determined group of academics from various Christian denominations has renewed efforts to reconnect with a regional past, to unearth traditions that may have been left behind or driven underground by Minahasan Christians trying to be modern, educated Indonesian citizens. These academics have put denominational divisiveness aside in order to gather pockets of knowledge about Minahasan history, ritual practice, and the evolution of contemporary religious terminology with roots in the pre-Christian era. Their goal is not to return to a purer, pre-Christian past, but to engage the question of how to understand and preserve the past as part of a Christian present.

Yet, these new alliances also bring cultural differences to the forefront. Just as the symbol of Watu Pinewetengan acknowledges the self-conscious unity of several sub-ethnic groups within an overarching ‘brotherhood’, contemporary Minahasans must actively work to smooth over the discrepancies that emerge in discussions about regional history and ritual practice. Part of the process of unearthing the past is to decide on what, exactly, should constitute the shared history of the Minahasan people.

For Pastor Renwarin, including local traditions in religious practice is an opportunity to ‘make people fall in love with adat (tradition or customary law)’ and gain better awareness of their own cultural heritage. Furthermore, he sees the development of new liturgies that combine aspects of pre-Christian belief with contemporary theology as a means to enrich contemporary Catholic practice. Over the past few years he has conducted traditional marriage rituals alongside standard Catholic weddings. Unlike the orthodox Catholic ceremony, he explained, local marriage rituals focus attention on the parents of the bride and groom, and the effect that their union will have on the extended family and larger community.

Pastor Roeroe, known for delivering fiery sermons in Tombulu in Protestant churches around the region, argues that older, pre-colonial patterns of leadership have made Minahasans into exemplary Christians

Pastor Renwarin’s contemporary, Wilhelmus Absalom Roeroe, a GMIM pastor and professor at the Christian University in Tomohon has a similar perspective. Pastor Roeroe has been an outspoken advocate for the inclusion of Minahasan cultural practices in the GMIM church. Known for delivering fiery sermons in Tombulu in Protestant churches around the region, he argues that the influence of older, pre-colonial patterns of leadership have made Minahasans into exemplary Christians. For these leaders, the value of returning to the ‘traditional’ practices of the past lies in their ability to improve and distinguish those Christian traditions that punctuate contemporary life in the region.

It is not only academics and religious practitioners who are interested in using the church as a vehicle of cultural preservation. Grassroots efforts by youth groups, Christian cultural organisations and individual churches attest to the fact that changing attitudes about the boundary between church and culture are not necessarily restricted to one particular sector of society. At the El-Fatah GMIM church in Lolah village, Tombariri district, a cultural committee composed of church members and clergy has been preparing ‘contextual liturgies’ to use during regular Sunday services. These liturgies are conducted in Tombulu and use repetitive melodies taken from pre-colonial harvest rituals. The original goal of the committee, according to founding member Hendrik Paat, was to preserve the Tombulu language and ensure its transmission to the younger generation.

In this case, including cultural practice in the church is less about participating in a regional identity than about maintaining the distinctive traditions and stories that make ‘Tou Lolah’, the Lolah people, distinctive within Minahasa. For some Lolah residents, there is little difference between preserving a Christian history and preserving Lolah’s local history. As one villager in his eighties told me, ‘The people of Minahasa in the past already knew God or Empung before Christianity arrived – but they had yet to know Jesus.’ Just as the Indonesian word for God has come to be used interchangeably in Lolah with the Tombulu term indicating a higher power, the boundary between the beliefs of the past and the religion of the present continues to be redrawn as Minahasan Christians reinterpret their history.

Making minorities?

Making the church a centre for cultural renaissance does raise the issue of how non-Christians will continue to fit within the frame of reference used to identify a person as Minahasan. Within the small but highly integrated Muslim population in North Sulawesi, there are many families who consider themselves to be Minahasan. They base this identification on ties of descent from the pre-colonial period when Muslim merchants immigrated and intermarried with local populations, or simply on the shared ethnic characteristics that make Minahasans or urban ‘Manadonese’ recognisable amongst other ethnic groups in Indonesia. One local Muslim, whose family members refer to themselves as ‘fourth generation Minahasans’, related how Muslims from other regions of Indonesia have questioned her religious identity due to the enduring association between ‘Minahasa’ and Christianity.

Locating the essence of Minahasa in the church risks making the boundaries of cultural identity coterminous with religious ones

In this region, where people take great pride in a history of openness and adaptability, where locals brag about their multi-religious extended families and Muslim and Christian neighbours celebrate important life events together, locating the essence of Minahasa in the church risks making the boundaries of cultural identity coterminous with religious ones. The extent to which religion will come to define local identity in a rapidly changing Indonesia is an important question not only for Minahasan Christians, but for the future of Minahasa itself. ii

Kelli A. Swazey (swazey@hawaii.edu) is a PhD Candidate in Anthropology from the University of Hawai’i Manoa and a Graduate Fellow at the East West Center. Currently conducting dissertation research in Manado, North Sulawesi, funded by a Fulbright grant, she has documented the lives of Minahasan Christians in Indonesia and the United States.