Sarah Anaïs Andrieu

The puppeteer Dadan Sunandar Sunarya performing the story Cepot Kembar |

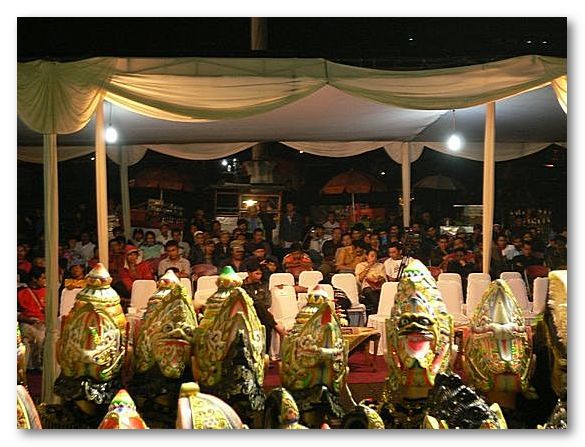

As often happens in West Java during November, rain had been falling all day, so Bandung’s central public space, known as the Gasibu, was half-flooded. A large temporary stage had been erected, in front of which stood a large tent sheltering about two hundred chairs. Forty chairs were prepared with white covers for use by government officials, but only about ten were present. Only a few spectators sat behind them. TV and radio crews busied themselves trying to protect their equipment from the rain.

|

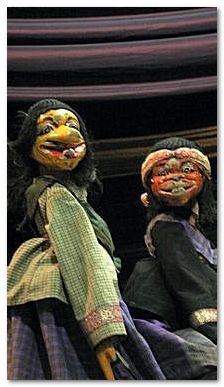

Dawala (left) and Cepot (right). Cepot

|

A performance of wayang golek, the traditional rod puppet theatre from West Java, was scheduled to take place for the entire night. The troupe was already on stage waiting patiently behind their gamelan instruments. The show should have already started, and a crowd should have already gathered around the stage as customarily happens, but very few people had dared to brave the rain and the cold on this night. The improvised market that always appears besides wayang golek performances was barely visible, with only a few sellers offering food and snacks from the shelter of huge umbrellas.

At last, the show started at around half past nine with speeches reminding the audience of the purpose of the performance, namely the protection of the national cultural heritage, of which wayang golek is officially a part. After the audience was reminded too that the event had been sponsored by the National Department of Culture and Tourism and its provincial subdivision in West Java, the committee finally gave a sign to the puppeteer, or dalang, that he could start performing the story entitled Cepot’s Twin (Cepot Kembar).

But soon after the first scene, the dalang stopped and introduced three famous Sundanese comedians who launched into an interactive dialogue with the audience. Spectators asked questions via SMS, which were relayed by the comedians to specialists from cultural and governmental institutions to be answered. After an hour of jokes and questions, the humourists retired from the stage and the wayang performance continued. The dalang recommenced his task of guiding the well-known characters through diverse intrigues and adventures. The rain had stopped, but there were still only a few spectators. Even fewer stayed until the performance ended at three o’clock in the morning.

The structure of the performance, something usually subject to quite strict convention, was upset by the intervention of the humourists just after the story commenced

What happened that night raises many questions about contemporary wayang golek. Government officials left the performance – if they came at all – long before its end. Much more seriously, the structure of the performance, something usually subject to quite strict convention, was upset by the intervention of humourists just after the story commenced. Such a thing could not happen in performances sponsored by rural communities or households. Moreover, the radio and TV broadcasts stopped after the comedians had withdrawn from the stage, even though the wayang performance would continue for a further three hours. For the broadcasters, the entire performance was too long and convoluted.

Local heritage, global value

There is some irony in the rather shabby treatment granted to the performers on this occasion, for it was not long ago that wayang was given its own space on the world’s cultural stage. In 2003, UNESCO proclaimed ‘Wayang Indonesia’ as a ‘Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’. Indonesia’s cultural bureaucrats responded to this recognition: the performers at the Gasibu were advised by the organisers that the performance was being held to honour Indonesia’s commitment to the preservation of humanity’s cultural heritage. But the events of the evening indicated that wayang golek, despite its global value, was encountering difficulties negotiating its status in contemporary West Java and Indonesia.

|

A patron inserts money in Cepot’s clothing |

Wayang golek is still considered an essential social and political media, as well as a mark of Sundanese identity within the national context. It also forms the basis for proud family heritages, as artists typically learn their puppetry skills directly from individual teachers who are often their own fathers. The UNESCO proclamation gave these performers hope of a worldwide audience, and since then, they have tried to have some say in the destiny of wayang golek.

How does wayang golek negotiate its status in contemporary Sundanese and Indonesian societies?

However, they feel it loses out on a national stage dominated by the culture of Central Java. The government, on the other hand, sees wayang golek as not only a distinctive regional genre, but also as something shared by the national Indonesian community. Since Indonesian independence in 1945, national cultural policy has attempted to gather the most important, aesthetic and spectacular traditions of each region as part of a unifying Indonesian culture. These icons are then disseminated throughout the country by the mass media and educational institutions as distinctive hallmarks of the regions – a practice that freezes regional culture and contributes to its standardisation. The UNESCO Proclamation enhances this process: after it was made, the government proposed a national action plan that included the creation of wayang schools, which would dispense standard teaching about wayang with adjustments for each regional ‘variant’.

Only bait

The Bandung performance illustrates an important paradox. On one hand, the government’s emphasis on heritage legitimises and supports the continued practice of wayang golek. But, on the other hand, it turns the puppet performances into a (profitable) museum exhibit, standardising them and preventing them from evolving.

|

Very few of the white chairs prepared for government officials were filled |

On that November night, the wayang were simply bait, used to attract the audience’s interest, then all too quickly relegated to the background as ethnic scenery for the transmission of other messages. In the process, this event intended to support and safeguard traditional cultural heritage was turned into a demonstration of the government’s lack of confidence in wayang golek. ii

Sarah Anaïs Andrieu (sarahanais@gmail.com) is a PhD Candidate in Social Anthropology and Ethnology at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris where she is writing her doctoral dissertation about the political anthropology of the Sundanese wayang golek and its process of patrimonialisation.

All photos by Sarah Anaïs Andrieu.