Sandra Bader

The Soneta Group performing at the launching of Sonet 2 BandSandra Bader |

The slogan ‘Dangdut Never Dies’, written in big letters, immediately leaped out at visitors entering the South Jakarta studio of TPI (Indonesian Education Television) on a Monday night in January this year. As they strolled through the building waiting for the event, they saw a number of famous dangdut legends hanging around, relaxing and chatting to each other. It appeared as if a big reunion of veteran dangdut stars of the 70s and 80s was taking place.

In fact, these celebrities were uniting to support and promote a new star in the dangdut community. They had gathered to celebrate the launching of Ridho Rhoma and his Sonet 2 Band. With this launch, Ridho is following in the footsteps of his famed father, Rhoma Irama, known as the ‘king of dangdut’. Through the Sonet 2 Band, Rhoma and Ridho are aspiring to breathe new life into the dangdut scene which has, according to them, run aground.

The king of dangdut

‘I am the founder of dangdut.’ This was the first thing Rhoma said to me when I interviewed him, before he set off on a narrative adventure that began just after the dreadful anti-communist massacres of 1965-66. It was around that same time that Rhoma Irama, a young musician, made his creative debut. Inspired by western rock music and the Malay sounds of the Orkes Melayu, Rhoma experimented by fusing Malay music with elements from rock, Indian and Arabic music. His new, energetic style invigorated the Malay music with fluid and dynamic rhythms and with this innovation he invented the distinctive genre now known as dangdut.

‘I am the founder of Dangdut.’ This was the first thing Rhoma said to me

With his Soneta Group and co-performer Elvy Sukaesih, Rhoma became the most widely recognised contemporary Indonesian musician and was crowned king of dangdut. ‘I created a musical revolution by transforming the Orkes Melayu into dangdut.’ Rhoma explained.

This new rhythm, with its lyrics dealing with the burdens of everyday life and love but touching also on social criticism and class discrimination, became immensely popular throughout Indonesia. Dangdut’s egalitarian character was an especially crucial factor in its popularity, for the music cut across class lines, appealing to the sensibilities of Indonesians of all sorts and most importantly, demonstrating sympathy with the life-worlds of the lower classes.

However, this sympathy with ordinary Indonesians devalued the music in the eyes of the upper classes, for whom it represented the culture of the village (kampungan). Moreover, dangdut’s development towards sensual and sometimes erotic dance movements has prompted some Indonesians to connect it not only with ignorance and a lack of sophistication but also with tasteless sexual displays.

A second revolution

|

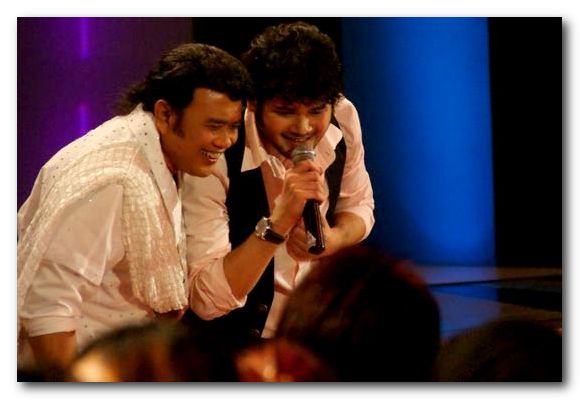

Rhoma and Ridho duettingSandra Bader |

In conversation about the development of dangdut music, Rhoma clearly expressed his dissatisfaction with the music’s evolution over the last few decades. Bewailing its current association with sensual and erotic dance movements, he insisted that there is only one way to dance (goyang or joget) to dangdut. Showing considerable pique, he jumped to his feet to demonstrate what ‘proper’ joget should look like. According to Rhoma, the new erotic dance style is one of the reasons for the ostensible decline in dangdut’s popularity. He remarked, ‘Since dangdut became eroticised the Indonesian people have begun to feel annoyed. Anybody who sees dangdut on TV will turn it off right away.’

Consequently, his burning ambition is to ‘safeguard’ dangdut from obliteration. He envisages a second revolution of dangdut music, to be achieved by encouraging and endorsing his son’s Sonet 2 Band. His objective is to take a stand against dangdut performers such as Inul Daratista and her characteristic ‘drill dance’ (goyang ngebor) which became extremely popular in 2003.

Dangdut’s development towards sensual and sometimes erotic dance movements has prompted some Indonesians to connect it not only with ignorance and a lack of sophistication but also with tasteless sexual displays

Inul’s dance style led to a massive controversy about the nation’s ‘moral health’. Indonesia’s senior Islamic clerics, the MUI (Council of Ulama), described her dancing as pornographic. The MUI regarded her appearance as a threat to morality and perceived the social stability of Indonesian society to be at risk. As a result, the MUI issued a legal opinion (fatwa) against her and she was banned from performing in several regions of Indonesia. Inul’s body became politicised, in the process bringing a number of important issues about Indonesia’s politics, culture and moral values to the surface.

Is dangdut disappearing?

A number of newspapers and magazines have recently published articles arguing that by and large, dangdut is disappearing, an interpretation which seems to affirm Rhoma’s impression that the music is currently in decline in Indonesia. This concern might appear to have substance if one observes the programs currently screening on Indonesian TV stations. For a long period, almost every station broadcasted dangdut programs as they jumped on the bandwagon created by Inulmania. ‘Indonesians love sensations.’ explained TPI’s production manager and Inul was certainly a sensation, becoming a star overnight with her trademark dance.

But then other ‘Inuls’ sprang up, like Dewi Persik with her ‘saw dance’ (goyang gergaji) and Annisa Bahar with her ‘broken dance’ (goyang patah-patah). After a while, the product became mundane and several TV stations, especially those with middle and upper class target audiences, turned away to search for new crowd-pleasers. As a result, only a few TV stations are currently airing dangdut shows.

Nonetheless, dangdut is still the genre in Indonesia’s popular music scene. It has the highest turnover of music recordings, albeit mostly pirated. More than two thirds of all dangdut recordings are reproduced illegally, causing financial difficulties for recording companies who have consequently refrained from producing new recordings. Very few new albums have been released lately, partly as a result of this persistent pirating of CDs, VCDs and DVDs. Dangdut also has to compete fiercely with the current surge of Indonesian pop music.

Sonet 2 – a second revolution?

|

Sonet 2 Band performing at the Trans7 studioSandra Bader |

Rhoma and Ridho and the five members of Sonet 2 Band are determined to counteract these recent developments, which appear to have left dangdut withering on the vine. For one thing, they are eager to improve what they regard as dangdut’s ‘seedy’ reputation. Apart from that, they aspire to achieve popularity on par with famous Indonesian pop and rock bands such as Slank, Dewa, Peterpan and others. They have been working hard towards this goal. They perform often and at diverse events, have released their first album and produced their first videoclip. Their album, called Menunggu, features 10 songs selected from Rhoma’s ample repertoire. The Sonet 2 Band has modified these songs by adding a dominant pop-drum beat in place of the beat of the tabla (an Indian percussion instrument) and the new guitar parts have given some of the songs a subtle rock strain. They have already attracted quite a following and if all goes well they will not be just another sensation but could succeed in opening a new chapter for dangdut. ii

Sandra Bader is a PhD student in Anthropology at Monash University researching dangdut music in Indonesia.