John M Miller

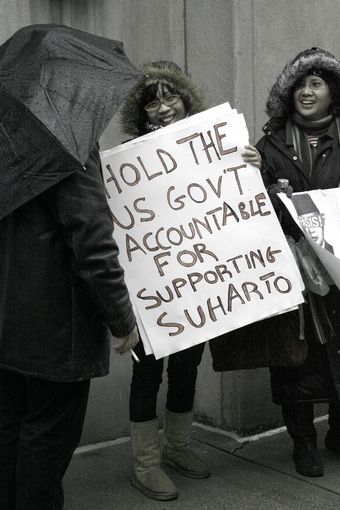

2 protesters outside the Indonesian Consulate in New York CityETAN |

President Barack Obama’s childhood ties to Indonesia were a much-discussed aspect of his campaign. In an effort to further mark Obama as ‘exotic’, his opponents played up the four years he spent in Indonesia as a child and his Indonesian Muslim stepfather. Obama himself preferred to emphasise the Kansas roots of his mother, but acknowledged the influence of his diverse background and the years he spent in Indonesia.

While Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s recent visit showed that some Indonesians are still excited about Obama and the promise of stronger US - Indonesia ties, it is not clear how long the honeymoon will last. Obama’s eventual policy towards engagement with Indonesia’s military could play a large part in determining the relationship.

A chequered history

The United States was the Indonesian military’s largest weapons supplier well into the 1990s, during some of the most repressive years of Suharto’s regime. Indonesian officers enjoyed prestige and promotions drawn from training with the US military. Some, including future President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, participated in training courses on United States military bases.

The issue of military assistance was largely off the radar until the 11 November 1991 Santa Cruz massacre, when Indonesian troops, some armed with US-supplied weapons, killed hundreds of unarmed East Timorese civilians engaged in protest. Ensuing pressure by activists and the general public was enough to force the US government to suspend many of its assistance programs. The International Military Education and Training (IMET) program, which provides US training to foreign militaries, was the first military assistance program to Indonesia that Congress restricted. As the Indonesian military and militia rampaged through East Timor after its independence referendum, the Clinton Administration belatedly cut all ties to the Indonesian military. Part of the ban was enforced by Congress.

The Bush re-engagement strategy has not ended the entrenched impunity of Indonesia's security forces

After the September 11 attacks in the US, the Bush administration muted human rights criticisms as it looked to Indonesia as a partner in its proclaimed ‘War on Terror’. The Regional Defense Counterterrorism Fellowship Program was started soon after the September 11 attacks to train Indonesian and other militaries restricted from receiving IMET, effectively circumventing the expressed will of Congress. The US and Indonesian military participated in joint exercises covering counterinsurgency and counterterrorism. By 2005, the government had reinstated nearly all military assistance programs and even added a few new ones.

Troublingly, in the last years of the Bush administration, some officials sought US training for members of Kopassus, Indonesia’s Special Forces unit. The US Senators Patrick Leahy and Russ Feingold, both leaders in human rights issues, actively opposed engaging the notorious unit, which has been responsible for some of the worst human rights violations in East Timor, West Papua, Aceh, and elsewhere. They argue that an existing law, named after Senator Leahy, forbids the training of military units credibly accused of human rights crimes. For now, US assistance for Kopassus training is on hold.

In 2008, the Indonesian Air Force sought to purchase F-16 fighters and C-130 Hercules transport planes from the US However, for the time being, Indonesia's current budget constraints and lingering wariness bred of past restrictions on assistance have limited Indonesia's appetite for new US weapons.

Now that Indonesia is eligible for unrestricted aid, its military can assume human rights issues no longer matter to their once and future patron

US military assistance to Indonesia has yet to reach the levels of the Suharto years. However, the number of Indonesian students in the IMET program is growing. And in 2008, US foreign military finance (FMF) funding, another aid program, jumped to US$15.7 million (A$23.1 million) from only one million dollars just two years earlier. In the end, the exact amount of any US military assistance may not matter. In the 1990s, the United States had restricted aid as a means to pressure for human rights accountability and reform. Now that Indonesia is eligible for unrestricted aid, its military can assume those issues no longer matter to their once and future patron.

Human rights pressure

Obama is certainly aware of the problems of the Indonesian military. In his book The Audacity of Hope, published in late 2006, Obama wrote that ‘for the past 60 years the fate of [Indonesia] has been directly tied to US foreign policy,’ which included ‘the tolerance and occasional encouragement of tyranny, corruption, and environmental degradation when it served our interests.’

The Bush re-engagement strategy has not ended the entrenched impunity of Indonesia's security forces for crimes against humanity and other serious violations committed in East Timor and elsewhere. The military continues to resist civilian control and emphasise internal security. The TNI’s ‘territorial command’ system remains intact. Efforts to implement a law ending the military's involvement in business have degenerated into farce, and its units remain involved in a variety of illegal enterprises, including logging and narcotics trade. The State Department's Country Reports on Terrorism credits the Indonesian police for ‘major successes in breaking up terrorist cells linked to ... violent Islamic extremist organisations.’ Its military goes unmentioned.

After Suharto was driven from office, the military relinquished a few perks, including its seats in parliament. While Indonesian domestic factors were important in the stalling of the reform process since that time, the US government’s decision to incrementally reinstate military assistance beginning in 2002 certainly didn’t help.

The victims of US-supported military abuses are clear about the need to leverage military assistance. East Timor's official Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation, called on countries to make military assistance to Indonesia ‘totally conditional on progress towards full democratisation, the subordination of the military to the rule of law and civilian government, and strict adherence with international human rights.’ This is not a call that the current government of Timor-Leste has echoed. It has decided not to press for trials of Indonesians indicted by the UN-backed Serious Crimes process, believing that Timor is too weak to challenge its dominating neighbour without international support.

Looking forward

One of Obama’s new cabinet choices already raises questions. Admiral Dennis Blair is the newly appointed director of national intelligence. The former head of the Pacific Command, Blair reportedly offered the Indonesian military increased assistance as its troops and militias wrought havoc in East Timor. At his confirmation hearing, Admiral Dennis Blair defended his actions in 1999. Despite praise of Blair from some committee members as someone who ‘thinks outside the box’, his actions in 1999 reflect longstanding thinking among US officials which values maintaining a good relationship with the TNI, regardless of results.

Obama has written that ‘for the past 60 years the fate of [Indonesia] has been directly tied to US foreign policy’

While some in Congress are looking to reinstate conditions on security assistance that would require progress on military reform, including the final divestment of military businesses, access to West Papua for diplomats and international humanitarian and human rights organisations, and credible trials for those accused of past human rights crimes in East Timor, West Papua and elsewhere, it is not clear if the new Obama administration will go along.

Expectations are high in Indonesia. Advocates have called on Obama and the US Congress to pressure Indonesia's government to respect human rights. Rafendi Djamin, coordinator of the Human Rights Watch Working Group, told the Jakarta Post, ‘We are now expecting Obama to put more pressure on Indonesia to resolve unfinished human rights cases by directly questioning the government about them and by addressing their importance.’ The US should ‘reinstate its military embargo against us’ another Indonesian activist said, ‘if Indonesia does not respond positively to US pressure.’

This February, Secretary Clinton made Indonesia one of her first foreign stops since taking office. Obama, too, has signalled his interest in visiting Indonesia - in late November, he reportedly told President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono that Indonesia will be his first visit to a Muslim-majority country. What human rights and reform message he will deliver when he goes is an open question. ii

John M Miller (john@etan.org) is the national coordinator of the US-based East Timor and Indonesia Action Network (ETAN).