David Reeve

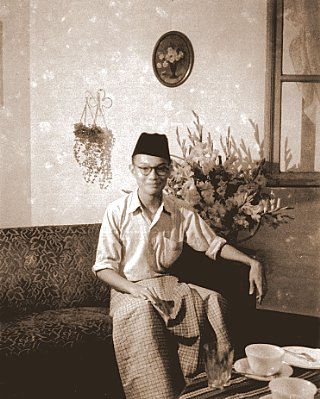

Ong in Bandung 1953 - 'deciding to be a good Indonesian'Ong family archives |

Ong Hok Ham, historian, public intellectual, eccentric and hedonist, died in Jakarta on 30 August 2007 at the age of 74. He was a celebrity historian in the 1980s and 1990s, writing for the daily Kompas, weekly Tempo, and periodical Prisma.

He was even better known for his eccentric lifestyle and for his love of food, drink, stories and laughter. He was an excellent friend to foreign reporters, diplomats, scholars and students, including a swag of Australians from the late 1950s.

It is rare for Indonesians of Chinese descent to become intellectuals; supposedly only interested in business. More surprising, Ong Hok Ham became an expert in Indonesian history, writing with a fully Indonesian voice. He was one of the Sino-Indonesians pointed to as models: Arief Budiman, Soe Hok Gie, The Kian Wie, Kwik Kian Gie, Teguh Karya - and Ong Hok Ham. He was said to be ‘more Indonesian than the Indonesians’, ‘more Javanese than the Javanese’.

Ong was an odd choice as a model, as he was a multiple-minority character in Indonesian society: Chinese descent, Dutch educated, atheist, alcoholic, pork eating, and gay. He never Indonesianised his name (like most Chinese in Indonesia), nor married (like most gay men in Indonesia).

Ong Hok Ham was born in Surabaya on 1 May 1933. His family was a hybrid Chinese-Dutch Indies type that has now disappeared. They set huge store by Dutch education, spoke Dutch at home, and used Dutch names. Ong Hok Ham was Hans. He dreamed in Dutch up to the end.

His family’s faith in Dutch colonialism received the rudest of shocks with the Japanese occupation of 1942 to 1945, and the declaration of Indonesian independence in 1945. By the late 1940s, the family started adjusting to living as part of the Indonesian nation.

Ong wanted to be a good Indonesian, but by 1953 he barely spoke the language

Ong was a clever boy at his Catholic Dutch school in Surabaya. He had one inspiring teacher, Brother Rosario, who set his historical imagination alight, and urged the students to become good citizens.

Ong wanted to be a good Indonesian, but by 1953 he barely spoke the language. So he moved to Bandung to Indonesianise himself, by repeating two years in an Indonesian school. He had the great good luck to be in Bandung for the Asia-Africa Conference of April 1955, and he worked as an assistant.

He started studying law at Universitas Indonesia (UI), but by 1957 had given up on his studies to work as an assistant for the Cornell professor Bill Skinner, researching the Chinese in Indonesia. This led to writing historical articles for the influential Star Weekly, 1958-1961. This was his Chinese phase, when he became well-known as an advocate for the assimilation of Chinese into Indonesian society.

From 1960 he studied history at UI, and came to love Javanese society and history, in both its aristocratic (priyayi) and peasant (abangan) variants. Like most Indonesians, he was increasingly appalled at the economic deterioration and political tensions of Guided Democracy (1959-1965), but with added personal tensions over his sexual identity, wanting and fearing love, wracked by desire and guilt.

The collapse of Guided Democracy, the mass murders, helped to unhinge Ong’s mind. He acted weirdly, and was swept up in mass arrests, jailed for six months in 1966. As he finished off his degree after release, he was great friends with an Australian couple, Blanche d’Alpuget and Tony Pratt. They fed him up and cheered him up; he said ‘they saved my life’.

In September 1968 Ong flew to America for doctoral studies at Yale University. What a time to study in America! - movements of all kinds, social ferment, and everywhere the issue of Vietnam. Ong’s personal problems shrank by comparison. He regained his confidence. His thesis was on Priyayi and Peasant in Madiun in the 19th century, a study of the social and economic impact of colonialism.

Ong returned to Indonesia in 1975, keen to make a career as a public intellectual. He published widely: colonial history, Javanese society, power and legitimacy, Indonesian economic history, the Indonesian Chinese, the social history of Indonesian food, Javanese spirits and legends, Indonesian paintings. He grew impatient with theory, and said ‘concentrate on the person’.

His major career was as a host and cook. He loved parties, food and drink, in large quantities. His critics said he wasted his talents; his admirers praised his gusto for life. His unusual house, built in separate pavilions in a Balinese-Javanese style, was home to many a party, where students and foreigners might meet Megawati Sukarnoputri, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Miriam Margolyes, and a host of scholars, writers and journalists. Ong had four main lovers, and while not proclaiming his sexuality, neither did he deny it. It was all great fun.

His life was narrow after a stroke in 2001. An Ong Hok Ham Institute, run by former students, seeks to carry on his historical work. ii

David Reeve (d.reeve@unsw.edu.au) is a senior visiting fellow in the School of Languages and Linguistics, University of New South Wales. He is writing a biography of Ong Hok Ham.