Creative Commons has a clear future in Indonesia

Alexandra Crosby and Ferdiansyah Thajib

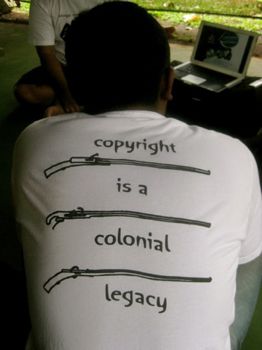

A video activist at Camp Sambel, Malang, 2010Heidi Arbuckle |

Over the last decade, conflicts between Indonesia and Malaysia have been increasing over who ‘owns’ a number of shared cultural products and practices, such as the kebaya, dangdut, batik, reog – even tempe. Both nations claim them, sometimes exclusively, as part of their national heritage. In Indonesia, anxiety around the ‘Malaysian menace’ has led some to call for intellectual property of culture to be more stringently defended. But when is the mixing of culture a threat and when is it the natural collaboration that comes through overlapping and shifting boundaries?

Ambiguity around the ownership of culture is nothing new. The flow of literatures, folklores, and performance is disordered and rarely stays within the borders of nations. In their digital form, cultural products are even more difficult to tie down. The internet has changed everything, speeding up these flows and presenting new challenges for tracking and maintaining copyright.

Creative Commons, a global licensing system that began in 2001, provides a free, public and standardised infrastructure that creates a balance between the reality of the internet and the reality of copyright laws. Copyright was created long before the emergence of the internet, and can make it hard to legally perform actions that we take for granted on the network: copy, paste, edit, source and post to the web. The default setting of copyright law requires all of these actions to have explicit permission, granted in advance, whether you’re an artist, a teacher, a scientist, a librarian, a policymaker or just a regular user.

In Indonesia, developments in technology occur very quickly. Indonesian is already one of the most commonly used languages in the blogosphere and Indonesians constitute one of the largest national groups of facebook users. With no real history of intellectual copyright enforcement, very few Indonesian internet users acquire permission before sharing digital culture.

The right to create

There is a particular history to intellectual copyright in Indonesia, which begins with ‘adat’ (traditional law) approaches to property and includes interpretation by the new nation in the 1950s. The term ‘hak cipta’ (the Indonesian word for ‘copyright’), which literally means ‘the right to create’, was coined in 1951 in Bandung, as a part of Kongres Kebudayaan Indonesia. At this conference, cultural artefacts were viewed as co-modifiable products for the construction of national identity, as they were throughout the formative years of the newly independent Republic of Indonesia. The term was invented as a replacement for ‘hak pengarang’, a derivative of the Dutch legal product called auteursrecht (‘author’s right’).

As a former colony, Indonesia inherited its membership at the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works from the Netherlands, which has been a formal member since 1912. But In 1958 the Indonesian government withdrew from the treaty in order to ‘develop the national identity of the newly born country without the restriction of knowledge, particularly through translated works’. This decision unleashed a massive surge of cultural production, particularly in the local popular music industry. The music scene in Indonesia thrived through various modes of copying and repurposing of Western songs. So great was the level of commercial piracy in the cultural industry that Irish folk musician Bob Geldof criticised Indonesia in the media after learning that his ‘Live Aid Concert for Ethiopia’ had been illegally distributed in the international market with a ‘made in Indonesia’ label. He had never recorded there.

Foreign pressure for the state to ratify the international law on copyright escalated in 1986 when the US government threatened to remove Indonesia’s exporting privileges if it did not enforce intellectual property law. This threat prompted the most rapid turnover in the country’s legislative history. Between 1982 and 2002, the Indonesian Copyright Bill was amended three times, each time in response to foreign pressure, particularly from the US. In its current form, the bill mirrors general copyright law, prohibiting unlicensed ‘sharing’ during the lifetime of the creator and for another 50 years.

In reality, however, copyright exists only on paper in Indonesia. The state has signed up to various copyright protection schemes such as the Universal Copyright Convention and the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights with the World Trade Organisation, and has renewed its membership of the Berne Convention in 1997. But implementation is fraught with contradictions and vulnerable to internal power plays. Under the New Order regime, for instance, crackdowns on piracy were complicated by its agenda or by political censorship. The government manipulated the laws in its campaign to prevent the distribution of pirated videocassettes in the mid-1980s, claiming the intention to protect Indonesian cultural identity from ‘unwanted foreign influences’, but also ensuring that political content was controlled.

During the Reformasi period, successive governments made more amendments to Indonesia’s Copyright Law, which was finally passed in 2003. But there remain serious incongruities between what has been legislated nationally and what is being implemented at the local level. Embedded in this set of problems are arguments about whether copyright enforcement is the most effective way to distribute knowledge if the objective is to promote economic development. Many producers believe that top-down systems of intellectual property actually widen existing gaps in knowledge, leading to increased piracy, particularly of digital content. Such relationships warrant a more complex discussion of intellectual property than one focusing on its legal aspects alone, and introduce the possibility of a Creative Commons system in Indonesia.

Use of Creative Commons

Creative Commons claims that it has become the global standard for sharing. Organisations as diverse as Al Jazeera, Google and the Nine Inch Nails have all embraced Creative Commons licences. In 2009 there were an estimated 350 million CC licensed works. In Indonesia many cultural producers see Creative Commons as a step towards clear licensing in a period of transition from offline to online distribution of content. Furthermore, Creative Commons is viewed by some as a way to address the limited availability of technology resources, which is due mainly to financial constraints. Many cultural producers already improvise by sharing whatever tools are required to achieve their goals. There is also widespread ‘borrowing’ of images, sounds and representations among activists and artists in Indonesia (sometimes breaching copyright), to ensure that the message they want to communicate can reach its target audience. The collective nature of the resulting works complicates the attribution of ownership and calls for a more versatile licensing platform that can facilitate the employment of collaborative approaches in content production and distribution.

Creative Commons is used by a handful of online information producers in Indonesia, including many bloggers and website administrators such as yesnowave.com and kunci.or.id. It has not yet been recognised under Indonesian law, though there are groups working toward this. Recently, a campaign was spearheaded by Wikimedia, the Indonesian chapter of Wikipedia, to advocate for formal recognition of Creative Commons. Wikimedia is committed to Creative Commons because, they say, content producers are hesitant to share their works online without a safe and open system. Some creators feel the need to reserve some of their rights, while others are concerned about whether their uses of content violate the copyright of others. Wikimedia says the only system that will work for everyone is Creative Commons.

Another group committed wholeheartedly to Creative Commons is EngageMedia, an Australian organisation now based in Jakarta. The primary focus of EngageMedia's activities is the EngageMedia.org video-sharing site, where all videos on the site use open-content licences and downloading for off-line redistribution is encouraged. Users must agree to a Creative Commons licence to upload videos to the site.

The Creative Commons system employed by EngageMedia is seen by the organisation as a step towards addressing the barriers to clear licensing faced by social-justice video activists in a period of transition from offline to online distribution of video. The fact that the organisation is a regional network with local bases was a key factor in the decision to use Creative Commons. With a focus on the distribution of activist content worldwide, clear and open licensing has been a priority since the inception of the network. ‘We are working on regional and global scales as well as local. So Creative Commons is important to us, to our funders, and to our users around the world, although it may not yet be important to Indonesian activists. We want to ensure that when Indonesian content leaves Indonesia it carries a signifier that says “share me” (to encourage further distribution) and also carries the protection of CC for that sharing’, says Andrew Lowenthal, General Manager of EngageMedia.

Roadblocks in the Commons

If Creative Commons is to move forward in Indonesia, an important issue to consider is public perceptions. There are content-producers and audiences who view Creative Commons as also being imposed from outside – part of what they view as a project of cultural imperialism. Creative Commons brings the system of copyright with it, relying heavily on an established legal framework. As a result of the traumas of Suharto's time, there is a high level of public disenchantment in Indonesia towards anything that has to do with legal systems.

Language is also a challenge for the implementation of Creative Commons. It requires not only the translation of many English terms, but also the use of familiar, day-to-day language as well as formal Indonesian, so that people understand the legal terms used in Creative Commons as well as the system’s possible applications.

Morever, there is some confusion about the scope of rights covered by Creative Commons. This arises from the fact that there is little clear explanation of how Creative Commons could be integrated into existing cultural practices. Many producers already label their material ‘Copyleft’, interpreting this as meaning ‘in the public domain’ (i.e. not copyright). Like Creative Commons, Copyleft is actually based on the concepts of copyright and, while the intention of Copyleft may be to provide open licensing, the effect of its implementation is unclear.

Clarifying how alternatives could work would be an obvious first step to improving the uptake of Creative Commons. The role of Creative Commons, or any other alternative licensing scheme, must be to re-establish interactivity and communication between creators and users. If implemented merely as a replacement for the current copyright system, or to compensate for the lack of a copyright system, Creative Commons cannot succeed.

A clear future

As licensing greatly affects how content can be distributed, effective distribution in a digital age requires alternatives to traditional copyright. In the future, debates over copyright issues will intensify in Indonesia, perhaps encouraging the development of open-content practices in the digital fields that can coexist with collective cultural production methods.

The barriers to clear and open licensing of digital content in a country like Indonesia, where tourists buy pirated CDs and DVDs of new releases on the side of the road for less than A$1, are immense. To establish a real grounding in the Indonesian legal system, Creative Commons needs mediation by lawyers, a cost that most digital cultural producers cannot afford. This is in addition to the gargantuan task of raising creators’ awareness of their right to adjust and control licensing of their own work. Organic initiatives to raise awareness about Creative Commons are now under way. Facebook, which has more than 22.4 million users in Indonesia, now has Creative Commons options for content.

Creative Commons clearly has a future in helping Indonesian producers create a licensing scheme that is open, democratic and able to respond to continuing cultural challenges. What is required to foster this future is a global system that is sensitive to local dynamics. Cultural activists are now working towards such a future, translating and adapting the framework of Creative Commons to an Indonesian context.

Alexandra Crosby (ali@alimander.com) is a writer and researcher. She is completing a PhD at the University of Technology Sydney and working for EngageMedia (http://www.engagemedia.org). Ferdiansyah Thajib (ferdi@kunci.or.id) is a researcher at KUNCI Cultural Studies Center (http://www.kunci.or.id) in Yogyakarta. If you are interested in Creative Commons, you should check out these useful links: http://creativecommons.org; http://www.slideshare.net/arijuliano/hak-cipta-creative-commons; http://www.ivaa-online.org/wp-content/files/Creative-Commons-Indonesia.ppt; and http://dailysocial.net/2009/03/23/wikipedia-indonesia-resmi-diluncurkan/.