Jeffrey A. Winters

Suharto kept the oligarchs in order.a-birdie (flickr) |

There has been a steady, but misplaced, undercurrent of dissatisfaction with Indonesia’s democracy. Rampant corruption, elected officials who perform wretchedly, indecisive leadership, and a surge in fundamentalist and sometimes violent Islamic politics have been blamed on Indonesia’s democratic opening after 1998. It is not uncommon to hear Indonesians at all levels of society express nostalgia for the order of Suharto’s New Order regime. Even some academics have added their voices to the democratic critique. Professors Ron Duncan and Ross McLeod, two Australian scholars, wrote in 2007 that economic growth rates were consistently higher under Suharto. After citing Churchill’s famous quote that democracy is the worst form of government except for all the others, they remarked that Indonesia’s post-dictatorship decline in economic performance ‘calls this view into question.’

Indonesia’s problem is not poorly functioning institutions of democracy. If anything, its democracy works remarkably well considering the damage inflicted on the body politic for a decade by Sukarno and then three decades by Suharto. Indonesia’s problem is that the country is beset by a stratum of powerful oligarchs and elites who are untamed. Electoral democracy is not designed to tame these actors. Indeed, they actually captured and now dominate Indonesia’s vibrant democracy.

It is a common error to blame democracy for the pathologies that result from a wild oligarchy. Instead of reverting to a dictatorship that tamed Indonesia’s oligarchs well, the daunting challenge that lies ahead is to constrain these powerful actors while maintaining an electoral democracy.

Why oligarchs?

Who or what are oligarchs and why does Indonesia need to focus on them? Every country with an extreme stratification of wealth has a group of actors at the top who are empowered by tremendous riches, which they deploy in defence of their fortunes. These oligarchs share the apex of the political, social, and economic realm with elites, who are powerful not because of wealth, but because of their positions, offices, or status. In places like Indonesia, there is a great deal of overlap between oligarchs and elites, with each group eager to join the other. The most enduring barrier in this interplay is for ethnic Chinese oligarchs, who are largely excluded from the elite category and have, instead, redoubled their pursuit of material power.

Unlike in the Philippines, where landed oligarchs arose during the nineteenth century under the Spanish, Indonesia had only elites and no oligarchs during the Dutch colonial period. Despite government programs designed to foster entrepreneurs, the Sukarno years were far too chaotic for a group of Indonesians empowered by concentrated wealth to emerge. It was during the sultanistic rule of Suharto that Indonesia’s modern oligarchs first arose.

Wealth in Indonesia today is vastly more concentrated in the hands of a few oligarchs than it has been in over four centuries. Data from Capgemini and Merrill Lynch show that in 2004 Indonesia had about 34,000 people with at least US$1 million in non-home financial assets, 19,000 of whom were Indonesians residing semi-permanently in Singapore. Their ranks grew to 39,000 by 2007, and 43,000 in 2010. Their average wealth in 2010 was US$4.1 million and their combined net worth was about US$177 billion (US$93 billion of which was held offshore in Singapore). Although Indonesia’s richest 43,000 citizens represent less than one hundredth of one per cent of the population, their total wealth is equal to 25 percent of the country’s GDP.

Although Indonesia’s richest 43,000 citizens represent less than one hundredth of one per cent of the population, their total wealth is equal to 25 per cent of the country’s GDP… Just 40 Indonesians hold combined wealth equal to 10.3 per cent of GDP

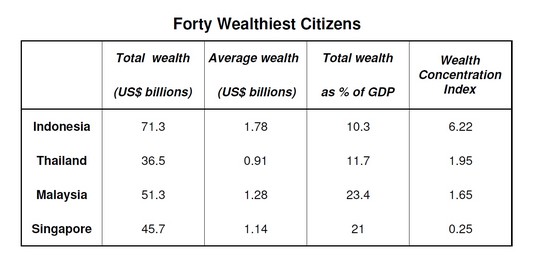

These figures tell only part of the story. Even among the rich, there is a relatively small number with very large fortunes. Just 40 Indonesians held combined wealth equal to 10.3 per cent of GDP in 2010. The following table presents comparative data on the 40 wealthiest citizens in four countries.

|

Forbes magazine 2010 ‘40 Richest’ reports for various Asian countries and author’s calculations. |

Two things are noteworthy. First, the 40 richest Indonesians are much more wealthy on average (at US$1.78 billion) than their counterparts in neighbouring countries. And second, the intensity of oligarchic concentration is extreme. The last column calculates a Wealth Concentration Index by adjusting the total wealth of each country’s 40 richest oligarchs (column two) relative to per capita GDP. Indonesia’s score of 6.22 is three times that of Malaysia and 25 times that of Singapore. Unlike a Gini Index, which is a blunt measure of the wealth gap between the top and bottom fifth of society, this Wealth Concentration Index is far more sensitive to the gap between the richest layer of oligarchs within the top one per cent and the average citizen in society.

The conclusion is clear. Indonesia has a significant and growing number of ultra-rich citizens. Among the 43,000 millionaires, there are several hundred citizens whose fortunes are US$30 million and higher (the level Capgemini defines as ‘Ultra High Net Worth Individuals’). Twenty-one of Indonesia’s richest 40 individuals or families were billionaires. The smallest fortune on the Forbes top 40 list for Indonesia in 2010 is US$455 million and the largest is US$11 billion (held by Budi and Michael Hartono). By comparison, Malaysia had the lowest top-40 threshold of US$110 million (though also the largest single fortune among the four countries compared – US$12 billion).

Running wild

In every society money is a form of power. But in countries like Indonesia, the role of wealth as a source of power is amplified by the absence of constraints on those who can deploy money for political and other purposes. Indonesia’s experience with democracy and its oligarchs demonstrates that taming a nation’s oligarchs and elites is a very different matter from simply having a democracy.

If allowed to run wild, oligarchs are capable of unleashing social, economic, and political damage far out of proportion to their numbers in society. The key question, including for achieving investment, growth, and job creation, is who or what constrains these oligarchs? Do they submit to a higher authority, or not? Having wild or tamed oligarchs is not a matter of democracy. In fact, it does not even seem to be related to the degree of freedom and political participation in a society. To understand this puzzle, it is useful to take a closer look at Indonesia’s democracy and how it has performed over the years.

If allowed to run wild, oligarchs are capable of unleashing social, economic, and political damage far out of proportion to their numbers in society

Indonesia has held three national elections since 1999, on time, every five years. It has also held hundreds of regional elections on a regular basis. Unlike in the Philippines, where election-related fatalities are high and candidates themselves are often assassinated, democracy is passionate but largely peaceful in Indonesia. Apart from the occasional irregularity with voter lists, Indonesians mostly follow the electoral rules, the parties take turns campaigning according to the published schedules, voters cast their ballots in secret, and losing candidates overwhelmingly step down without resistance. There is freedom of assembly, of expression, and of the press. Issues get debated as parties and candidates try to shape the discourse. This includes sometimes unleashing dirty tricks against opponents. Most importantly, the winners are not known in advance. There have been surprising and sometimes spectacular wins and losses.

By these measures, Indonesian democracy is performing to a very high standard and the country has an increasingly vibrant civil society. It is true there is something very wrong and even dysfunctional in Indonesia’s political economy. But the new electoral democracy is not the problem. Likewise, and perhaps somewhat perplexingly, democracy is unlikely to play much of a role in reaching a solution.

Two transitions

To understand what plagues Indonesia, including its worsening economic performance, it is important to recognise that two transitions occurred in 1998. One was the momentous transition from dictatorship to democracy that everyone talks about. The other was an equally important though much less visible transition from tamed to wild oligarchs and elites.

Suharto not only created the country’s oligarchs practically out of nothing, but he controlled them like a mafia Godfather. No matter how big or rich you became, Suharto could break you. All issues of wealth defence, property claims, and contracts radiated out from the Don. This put a premium on the politics of proximity. The more that was at stake, the more vital it was to have access to the inner rings around the dictator, if not to the man himself.

Suharto was first among equals. A key element in operating such a sultanistic oligarchy is that all competing bases of independent power must be blocked. Suharto and his cronies made sure this was so across the entire economy and bureaucracy. As a matter of historical accuracy, it is not Suharto who destroyed Indonesia’s legal system. The work of the American political scientist Daniel Lev makes clear that the relatively strong and independent legal system that existed in the early 1950s was subverted by General Nasution and President Sukarno. Suharto finished the job and made sure that the only recourse oligarchs had, and the only thing that could reliably tame them, was the dictator himself. Suharto’s most significant contribution to Indonesia’s crippled system of law was to ensure it could not recover from the devastating blows it sustained during the Guided Democracy period.

One of the most important factors that weakened Suharto’s New Order is that once his children grew up, they disrupted the system of wealth defence and oligarchic taming based on the politics of proximity. Suharto’s children rapidly became the most predatory and disruptive force within Indonesia’s oligarchy. It was no longer possible to turn to the Don to secure property, enforce contracts, limit predations, and manage risks. The New Order went from being a highly predictable and tame oligarchy, which promotes investment by wealthy oligarchs, to being a frustrating and increasingly difficult system for them to navigate within. Not only did Suharto’s children engage in predatory behaviours that threatened oligarchs and the economy, but an entire cohort of actors linked to the children grabbed a piece of the action as well.

When it became clear that powerful figures like General Benny Murdani and even General Prabowo could get in trouble with Suharto for speaking up about the disruption the children were causing, Indonesia’s oligarchs knew that the reliable system of security and response based on proximity was broken. The final straw came when Suharto started grooming some of his children for political succession. This ominous development occurred just prior to the onset of the financial crisis in 1997. It is not that Indonesia’s elites and oligarchs (and equally frustrated foreign counterparts in places like Washington and New York) brought Suharto down. Rather, they stepped aside as he faced his last crisis. Everyone, including the students in the streets, could see that Suharto was exposed.

When the dust finally settled, and democracy took shape, all of the oligarchs and elites were still there. Virtually none had gone down with Suharto. Oligarchic and elite continuity was nearly 100 per cent. But two things had changed. One was that the actors at the top had to adapt to the new democratic game. Not only did they do this with relative ease, but they were better positioned than anyone else to capture and dominate Indonesia’s electoral politics.

Whereas oligarchs in the Philippines and some Latin American democracies are armed and can set their militias on each other, Indonesia’s oligarchs, for historical reasons, were disarmed from the start. This has facilitated the game of democratic spoils among them and kept the competition orderly. They had the money, the media empires, the networks, and the positions in the parties (or the resources to create new ones) that allowed them to dominate the new democratic system. To contend for office (or, for the ethnic Chinese, to fund indigenous Indonesians who ran), oligarchs had to deploy huge sums of money, down to the village level.

The nub

The other thing that changed, however, is that Indonesia turned overnight from Suharto as the source of oligarchic constraint to the country’s debilitated system of laws. This gets to the nub of the problem. There were and are no strong, independent, and impersonal institutions of law and enforcement to which Indonesia’s most powerful actors must submit. They participate with the rest of society in the processes of electoral democracy. But on matters of property, wealth, economy, corruption, and criminality of all kinds, the law bends to individual oligarchs and elites rather than the reverse. The simple reason is that they have the resources at their fingertips to buy the legal system, from the police and prosecutors up to the judges and politicians.

Interestingly, large parts of the Indonesian legal system, in a mundane way, function routinely. It is not a lawless society. For the vast majority of Indonesians, the ‘low’ rule of law operates. Where it dysfunctions, it is more a technical or professional matter than a reflection of the ability of people to intimidate it. It is only when one moves up the system and oligarchs and elites are involved – what might be called the ‘high’ rule of law – that power defeats the legal system.

This failure of the legal system to tame the most powerful players is where issues of governance truly arise. The epicentre of the struggle over the rule of law is where oligarchs and elites clash with the impersonal institutions of the state. This titanic confrontation of power is not amenable to repair by World Bank development loans to train judges. Technical fixes are relevant only as one moves down the power hierarchy toward the ‘low’ rule of law.

This struggle also has little if anything to do with democracy. Although often thought of as the same thing (or at least intimately related), democracy and the rule of law are quite distinct. This is not only apparent in Indonesia, where democracy is robust and yet captured by criminal figures the law cannot constrain. But it is even more evident in the case of Singapore, which has a strong and independent system of law but no democracy. By viewing democracy and the rule of law as distinct, it is possible to explain Indonesia’s ‘criminal democracy’ and Singapore’s ‘authoritarian legalism.’

It was not the absence of democracy that was important under Suharto, but rather the presence of effective constraints that tamed oligarchs and elites. This promoted capitalist investment and growth. And conversely, it is not the presence of democracy since 1998 that is the problem, but instead the absence of an impersonal system of constraints on oligarchs (the rule of law) that could tame them as Suharto’s personal system once did.

One of the most important lessons from Indonesia is that transitions to electoral democracy are far easier to accomplish and sustain than imposing a system of laws to tame a country’s most powerful actors. As the Philippines, Indonesia, and Egypt show, eruptions of people power (including mobilisations of the last minute) can topple a dictator and usher in electoral democracy. But they have almost nothing to do with how the ‘high’ rule of law gets implanted or grows. The problem is all the more daunting when it is oligarchs and elites themselves who capture and dominate the well-functioning democracies mass movements create.

Jeffrey A. Winters (winters@northwestern.edu) is professor of political economy at Northwestern University. His new book from Cambridge University Press is entitled Oligarchy.

This article is part of The Rich in Indonesia feature edition.