Chang-Yau Hoon

Students praying at a weekly chapel serviceChang-Yau Hoon |

Exceptional academic performance, faith education, strict discipline and a safe environment are some of the factors that attract ethnic Chinese to enrol their children into elite Christian schools in Indonesia. In fact, these schools have become a thriving business across major cities, generating handsome profits from the provision of high quality education. They are generally attended by Chinese Indonesian students from a middle and upper class background. The schools are equipped with much better facilities than most schools in Indonesia and charge a considerable fee - sometimes in US or Singapore dollars. Parents do not seem to mind paying a premium for the excellent academic reputation enjoyed by the schools.

But, like other exclusive environments, elite Christian schools are potentially sites for the reproduction of ethnic, class and religious difference. The twin effects of high tuition fees and Christian education mean that few indigenous Indonesian students attend because they either cannot afford the fees or are deterred by the schools' focus on Christian values. Consequently, students in elite Christian schools grow up in a largely homogenous environment having little knowledge and interaction with the diverse and multicultural community in which they live.

A tool for social segregation

Contemporary elite Christian schools share some resemblance with colonial schools in terms of the social hierarchy. Schools became an important site for social segregation in the archipelago in the Dutch colonial era when the population was divided into three racial groups with different legal rights and privileges, including access to education. When the Dutch laid the foundations for European and native education prior to the twentieth century, the Chinese were largely left to their own devices. Things changed with the rise of pan-Chinese nationalism in Southeast Asia in the early twentieth century and the founding of the Tiong Hoa Hwee Koan (the Chinese Organisation) in 1900. This organisation established schools in Batavia to provide modern education to both peranakan (Indies-born or 'mixed' blood) and totok (China-born) Chinese. Fearing that the Tiong Hoa Hwee Koan and its schools would orient peranakan Chinese politically towards China, the Dutch colonial administration established the Dutch Chinese School in 1908, which attempted to teach Western values through the medium of the Dutch language.

The Dutch Chinese School was one of three types of elementary schools established by the Dutch. The system reflected the colonial racial hierarchy, with the European elementary school at the top, followed by the Dutch-Chinese school and finally the Dutch-Native school. Admission was restricted to students of the particular racial community and school fees were charged accordingly. As many Chinese desired a European education for its social status, the Dutch-Chinese school used Dutch as its language of instruction, and was classified as western elementary education, to which the European School Regulation applied. In contrast, the Dutch-Native school used Dutch together with Malay or local languages in its curriculum but was governed by the Native School Regulation. The Dutch-Chinese school was not just an exclusive school in terms of its racial composition. It was also elitist, serving mainly the upper-class Chinese. To some extent, this exclusivism still resonates in contemporary elite Christian schools.

Faith, knowledge and discipline

Christianity experienced a boom among ethnic Chinese in Indonesia during the New Order (1966-98) when the Suharto administration actively promoted religious affiliation to prevent the re-emergence of Communism. This boom, coupled with the closing of Chinese schools, resulted in rapid growth in the number of Christian schools. Some ethnic Chinese would not consider sending their children to state schools because of the standard of education provided. Those who wished to take advantage of state education experienced discrimination when seeking admission into state schools, which further fuelled the demand for alternative schooling outside the public system. In response to such demand, some Chinese Christian churches started to establish privately-funded faith schools. Chinese Christian schools established prior to the New Order experienced an unprecedented rise in enrolments. These schools became well accepted among the Chinese, both Christians and non-Christians, who valued the quality of education and discipline provided by the schools. The schools are mainly managed by educational foundations established either by Chinese churches or wealthy Chinese Christian business people.

James Riady is the Chinese-Indonesian CEO of the Indonesia-based transnational business empire, the Lippo Group. He is also the founder and chairman of Pelita Harapan Educational Foundation, which he established to address the 'failure' of secular education. The Foundation has built a world-class university and several elite schools in Jakarta catering mainly for the ethnic Chinese. Like many elite Christian schools, Pelita Harapan promises to deliver high quality education with conservative Christian values and discipline. Great importance is placed on faith, as the schools see themselves carrying the mission of making disciples in all nations. Spiritual development is also emphasised, and students have to participate in faith activities such as Christian religious classes, daily devotion, morning prayers and weekly chapel service, which staff must also attend. Teachers are also expected to be actively involved in building the faith community by leading bible study groups, fellowships and prayer meetings.

|

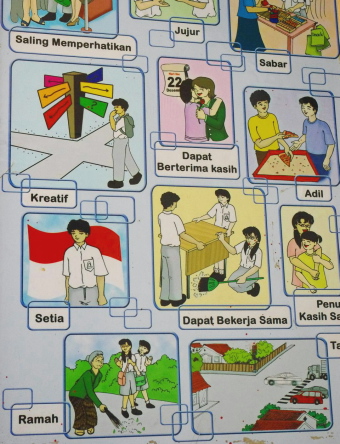

Poster encouraging disciplineChang-Yau Hoon |

Christian parents send their children to these schools because they want their children to be immersed in an environment that models the faith practice of their home or church. But these schools appeal not only to Christian parents. Many non-Christian Chinese parents also find Christian schools attractive because of the concentration of ethnic Chinese in the schools' population, the exclusive social environment, academic accomplishments and discipline in the schools. Building their reputation on academic quality, these schools compete fiercely to outperform one another in national examinations and international competitions, such as the Science Olympiad. The schools often showcase medals and trophies in glass cupboards by the entrance.

Another major selling point is the promise of strict discipline and 'character building', which is infused through strict Christian values and discipline. In one particular school, character building classes encourage students to develop social sensitivity through participation in social and spiritual activities such as bible camps, social programs, mission trips and fellowships. According to the school's founder, however, this program is not designed to equip students to live with differences in a multicultural and multi-religious society. Hence, the 'social sensitivity' that the school teaches only extends to helping students to be sensitive to the potential threat of the secular world to their faith and morality, but says nothing about how to live in it.

This school is not alone. Elite Christian schools have provided a safe environment and an alternative to state education for the ethnic Chinese. But despite their positive contribution to Indonesia's education landscape and to the development of Chinese Indonesian students, their exclusivity has become a site for the construction of difference in religious, ethnic and class identity. It is ironic that in protecting students from the temptations of the secular world, elite Christian schools have deprived them of learning how to love their neighbours who come from a different background.

Chang-Yau Hoon (cyhoon@smu.edu.sg) is Assistant Professor of Asian Studies at the School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University. He is the author of Chinese Identity in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Culture, Politics and Media (2008).

This article is part of the Learning to Belong feature edition.