Australia's journey with Indonesia was reflected through its engagement with Rendra's visits

David Reeve

I first met Rendra in 1969, when I was in Yogyakarta to improve my Indonesian. To my great shame, having learned Indonesian at a languages school on an airforce base on the far outskirts of Melbourne, I didn't know who he was. A friend in Yogya had asked me to take a fourth hand at bridge with another couple - some sort of a writer and his wife. So it was at bridge that I met Rendra and Mbak Narti. But it was only when I saw one of his plays, Oedipus I think, that I realised that he was far more than someone who did a bit of scribbling on the side.

Rendra's long relationship with Australia is in some ways a prism for the Australia-Indonesia relationship in general and for the changing political climates and commitments of both nations. He first came to Australia in 1972 at the invitation of PEN, the worldwide organisation of writers, formed to promote friendship and co-operation among writers everywhere, whilst fighting for freedom of expression. This was an appropriate sponsor for a writer who indeed fought for freedom of expression under both Sukarno and Suharto. This was a time of great interest in Indonesia from various parts of Australian society. Who could better address such interest than this impassioned and fearless intellectual, with his deep interests in literature and social conditions?

It was the start of a relatively close relationship between Rendra and Australia. Some recurring figures in Rendra's multifaceted relationships with Australia were his translators and friends Harry Aveling, Max Lane and Suzan Piper. However, many others valued their links, meetings, audiences and friendships with Rendra and I believe that he welcomed Australian interest in Indonesia. Harry Aveling had produced a 32-page translation of Rendra's poetry for a University of Macquarie seminar on poetry of the South Pacific in August 1971. Three years later, with Derwent May and Burton Raffle, he published the bilingual collection of Rendra's Ballads and Blues for Oxford University Press. Rendra was also well-represented in Harry Aveling's Contemporary Indonesian Poetry, published by Queensland University Press in 1975. This was much used in schools as Rendra's poetry began to enter the school curriculum in the 1970s and 1980s. At that time it seemed almost natural that the two peoples should be friends.

When Rendra was detained for almost six months in 1978 on the grounds that his poetry 'spread hatred' against the Indonesian government, Australians joined in protests against his detention. Following his release he faced continued restrictions on his freedom of expression, being denied venues and permits to perform. The Australian-based Committee Against Repression in the Pacific and Asia (CARPA) organised as their founding activity a 'Free Rendra' campaign in Australia. They sold cards with his poetry and paintings by politically controversial 'New Art' painter Hardi to help fund a national speaking tour of Australia by Rendra discussing his work and experiences in Indonesia. Some of these cards are published in this edition.

In June 1980 Rendra was to attend rehearsals for a staged reading at the Belvoir Street Theatre, Sydney of his 1975 play The Struggle of the Naga Tribe, translated by Max Lane and published by Queensland University Press in 1979. However, Indonesia denied Rendra an exit visa and Bengkel Teater senior member Edi Haryono came in his place. As CARPA activist, Helen Jarvis, has described elsewhere: 'The house lights dimmed and a hush descended over the audience. A crackly voice came over the loudspeaker - Rendra was speaking by telephone from Yogyakarta extending greetings to those attending the solidarity reading of his work … [and expressing] his thanks to the support given to him...' Later that year Harry Aveling's bilingual edition of Rendra's 'troublesome' political poetry, Potret Pembangunan dalam Puisi (better known as Pamflet Penyair) was published by Wild and Woolley as State Of Emergency.

Poet and cultural statesman

Rendra visited Australia three more times over the next three decades. In September 1988 he was a guest of the Carnivale in New South Wales and the Spoleto Festival in Victoria. Janet Hawley in her September interview with him in The Age that year asked him how he felt to be performing again after his seven year ban and being allowed to visit Australia after being refused an exit visa twice. He expressed great relief, stating 'It is a sign of change in the nuance' - referring to the early stages of the brief period of keterbukaan, or openness. He went on to favourably compare Australia to Indonesia, observing that in Australia the people are above the government while the opposite prevailed in Indonesia, with no freedom of the press.

In April-May 1992 Rendra performed in Canberra, Sydney and Melbourne, on a tour produced by Arimba Culture Exchange and sponsored by a wide range of backers including the Australia Indonesia Institute and Insearch. He read poems from his award-winning Orang-orang Rangkasbitung (Rangkasbitung People) collection, translated by Suzan Piper. The visit attracted wide print and electronic media coverage, with Rendra giving interviews on a broad range of subjects. 'They got Keating and we got Rendra!' was the common cry, said Arimba producer, Margaret Bradley, Prime Minister Paul Keating being in Indonesia at the time.

|

|

Rendra and Ken Zuraida visiting the National Maritime Museum / Jeffrey Mellefont |

As with other visits, enduring contacts were made in various domains. Insight into Rendra's practice was enabled through performances and workshops at Belvoir Street Theatre in Sydney, the Australasian Playwrights' Conference in Canberra and Grant Street Theatre and La Mama in Melbourne. Australian theatre groups such as Entr'Acte Theatre, Jigsaw Theatre and Kinetic Energy Dance Theatre and Australian theatre practitioners such as Ta Duy Binh, Robert Draffin and Mary Sitarenos, subsequently developed close working relationships with Rendra and his theatre group.

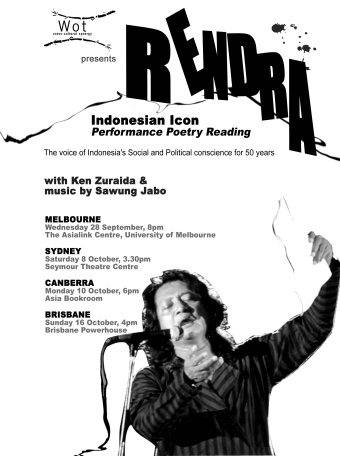

Rendra was on the eve of his 70th birthday when he visited Australia with his wife Ken Zuraida in September-October 2005, on a tour organised by Wot Cross-Cultural Synergy. This time he was more the senior statesman: slower, dignified, reflective. At the talk at the Queensland Art Gallery sponsored by Griffith University, Rendra spoke on Indonesia's perceptions of Australia. It was a charged time. The second Bali bombing had occurred three days into his visit so the major media were preoccupied with a different aspect of Indonesia. Australia's then Prime Minster John Howard's earlier talk of pre-emptive strikes into the region led Rendra to comment that he sounded imperialistic to Indonesian ears. He criticised Australia's overly close relationship with America, saying that 'The Indonesian people preferred Keating. Under Keating Australia stood proud, convinced of its own worth. Indonesia was proud of its neighbour Australia under Keating for taking an independent stance; his physically embracing the Queen, so Australian.' He was contemptuous of John Howard, commenting that, 'I think he was born in Philadelphia.' But he spoke warmly of such notable figures as the humanitarian and academic, Herb Feith, and Australian support for Indonesia from the 1940s onwards, and also of the support shown to him during tours here when he was still banned at home.

But Rendra did not appear to be a great fan of Australia's form of democracy. He had strong opinions on many matters and was a strong Indonesian nationalist. The Australian stance in critique of Indonesia's role in East Timor angered him. However, ultimately he was looking for a moral change in people at all levels. He had a deep commitment to justice and hatred of injustice and inequity in society and believed that Australia had a role to play in offering an alternative West in Asia.

David Reeve (d.reeve@unsw.edu.au) is busy in retirement writing and encouraging Australian students to include one or two semesters at Indonesian universities in their study programs. This article draws on information provided by Arimba Culture Exchange producer Margaret Bradley (arimbace@tpg.com.au) and Wot Cross-culture producer Suzan Piper (suzan@wotcrossculture.com.au).