Bramantyo Prijosusilo

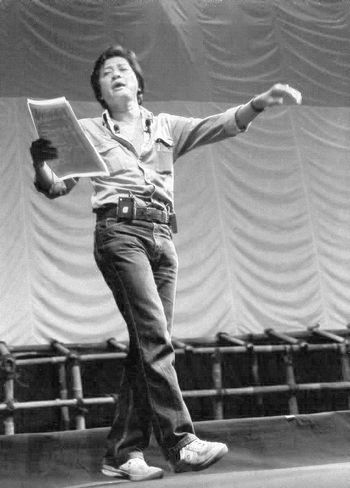

Rendra reading poetry on his return to public performance at

|

Rendra was still banned from performing in public in 1983 when I joined his theatre group in an East Jakarta neighbourhood. However, his collection of essays entitled Mempertimbangkan Tradisi (Considering Tradition) had just been published. In one of the essays he retold the story of how the young prince who was to become Sultan Hamengkubuwana I of Yogyakarta would go to the Pepe river that divided Rendra's childhood city of Solo and throw two diamond rings deep into the river, and then dive in repeatedly until he had retrieved them. The essay also described how the prince's classroom was a 'cyclorama-delux' of the real world, where in real time he faced culture and nature.

Rendra often said that he began his basic training as a poet when he was very young. One informal teacher was a certain Mas Djanadi, sent by his grandparents to look after Rendra when he was four years old. From Mas Djanadi, Rendra learned traditional Javanese meditation and kapujanggan (poetry). One key principle of kapujanggan that Rendra adhered to throughout his life was the concept that the poet must be immersed in contemporary reality - manjing ing kahanan were Mas Djanadi's words. Djanadi always ensured that young Rendra always carried out his chores: making his bed, helping fetch water from the well to bathe his siblings and sweeping the floor when it was dirty. It was important to be concerned for one's environment and those in it.

Another of young Rendra's teachers was his mother, a dancer of sacred dances in the Solo palace. She introduced him to meditation and the concept that the poet guards the spirit of his nation, just as the king cares for the people's welfare. Rendra elaborated on this concept in his 1975 acceptance speech on receiving the Jakarta Academy Award. Frustrated by bans on performing his plays in his home town of Yogyakarta, he distinguished between the body and spirit. The body is institutions, law and customs, he said, but values and dreams are the spirit that religious leaders, intellectuals and the artists must guard. He positioned himself as a poet living in the wind, unfettered by any institutional ties.

Bengkel Teater meditations

The concept of the duality of culture and nature, which Rendra employed throughout his career, originated from the discourse of the Javanese poets. It was particularly apparent in the meditation techniques that later became part of the Bengkel Teater Rendra curriculum. By the time I joined, all this was part of the communal culture and practice. There were meditations to increase the powers of sensory perception other than the visual, because 'the eyes are used all the time in culture'. We were told to sit with the backbone straight and relaxed, let culture subside and nature free. After achieving a certain intensity we were then told to move and 'follow our nature'.

In the 1970s Rendra met and became a student of the master of the Bangau Putih silat (White Crane martial arts) school, Suhu Subur Rahardja. He told Rendra that the exercises he was teaching his disciples resembled silat exercises to develop inner power. From then on the kapujanggan meditations Rendra taught were complemented and often validated by White Crane silat techniques. Rendra asserted that this inner power could be employed in the service of art, and he demanded that his actors develop it through the diligent practice of silat and Javanese poetry exercises.

One unique Bengkel Teater meditaton exercise was the gerak nurani (inner flow), which was taught to Bengkel students to develop sensitivity and energy. I was taught this exercise in 1986 when Rendra was finally allowed to perform again. It was past midnight in the house in Depok where around forty Bengkel Teater Rendra members lived and conducted theatre workshops. All of us practised silat for up to eight hours a day and at night we would have theatre workshops. From his house around the corner, Rendra commanded us to be on standby. We were to conduct gerak nurani that night, and members with previous experience were instructed to assist the first-timers.

From the ventilation opening above the door Rendra scattered kitchen refuse and other material on us

Yelling at us for leaving garbage out, Rendra ordered us all into a tiny bathroom in his house and locked us in. It was so full that people climbed up and into the Indonesian shower tub. We were stifling hot. Someone standing in the middle of the floor suddenly went beserk and began kicking and swinging punches. From the ventilation opening above the door Rendra scattered kitchen refuse and other material on us. People were screaming and crying.

A senior member of the group standing on the tub was repeatedly kicking the offender in the face as others shouted at him to stop kicking. Pepen, our silat instructor, reached over their heads and with one hand grabbed the frenzied man by the hair and lifted him up. He immediately fell limp, and dropped to the floor, sobbing. Others doused him with buckets of cold water, soaking everyone else in the process. The shouting and screaming stopped and Rendra ordered us to come out, calling our names one by one. Outside the living room was dark, its tiled floor wet and slippery but Rendra told us to run, fast, to the farthest side of the room and sit down.

When everyone was out of the bathroom and seated on the floor we began to meditate, first motionless. Then we were given directions to begin the gerak nurani. 'Just follow your inner voice, anything you want to do, just do it!' Participants began to cough, wheeze, roll on the floor, scream, cry, twist, turn, groan - it was as if each participant had been swept away by some stream of consciousness. The whole class forgot about time until Rendra clapped his hands and ordered us out of our trance. The floor and all our clothes were dry. We were all feeling great, full of energy and fresh, although it was near dawn. Rendra then told some participants to improvise a scene based on a given theme. He asked one man to play the grandmother of another. The actor curled up his toes as if his feet were bound, and began speaking what sounded like Chinese. Later we discovered this man's grandmother was a Chinese woman who indeed had bound feet.

As it grew light we gathered around to review the exercise. The man who had been repeatedly kicked in the face had neither scratches nor bruises. 'That is because he was kicked with hatred, not with compassion; compassionate blows always hurt more', explained Rendra, who believed that compassion and love were the most basic discipline of the Javanese poet. In order to produce relevant art, he would often say, one must be disciplined in the practice of compassion and love, which develops concern. 'It is concern that allows you to be grounded in reality. Not merely your own reality, but also the reality of nature and the reality of your times. These are the three mountains on which your two feet must always stand.'

Bramantyo Prijosusilo (bramn4bi@yahoo.com) is an artist and organic farmer now living in Ngawi, East Java, who writes for the Jakarta Globe and Tempo and performed with Bengkel Teater in the 1980s. Rendra's methods and excercises are still used in the workshops in the Bengkel Teater Rendra campus in Cipayung and also in the White Crane Martial Arts School in Bogor.