Vannessa Hearman

The Trisula MonumentVannessa Hearman |

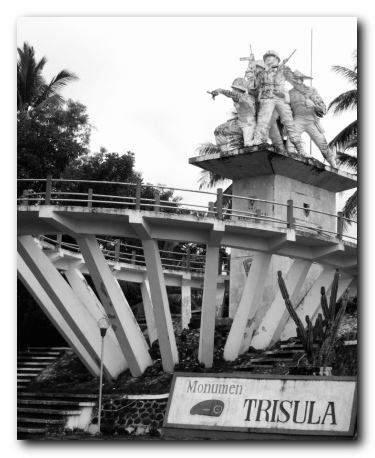

The Trisula monument in Bakung in South Blitar, East Java, stands high above a visitors' parking lot, completely empty except for our small vehicle. With the sweeping views across the hills and coconut groves around the village, visitors are tempted to linger and enjoy the fresh air, perhaps unaware that their movements are observable from a small police station below at the foot of the hill.

The monument, built as a joint effort between the military and local people to commemorate what is said to have been a counterinsurgency operation against remnants of the PKI (Indonesian Communist Party), is also symbolic of the monitoring and surveillance the area was subjected to after the local people were accused of harbouring communists in the 1960s.

Running for their lives

By March 1966, many PKI leaders had been killed or had disappeared, presumed dead. By the end of that year, those on the run had few places to hide or people to turn to for support. Safe houses were becoming scarce and repression was spreading. Despite the difficulties they faced, remnants of the PKI leadership tried to reorganise and an 'emergency' Central Committee was hastily appointed to salvage what was left of the party. Surviving members moved to set up bases in several different parts of Java in an attempt to regroup, spurred by the pressures that military operations exerted on them. One such place of retreat was South Blitar.

According to Rewang, a member of the PKI's Central Committee from Central Java, dozens of PKI members sought refuge in this isolated pocket of East Java. Their main motivation was to find somewhere safe. For example, Tuti, a provincial level Gerwani leader, had been a courier, passing on messages and hiding important party leaders. Before coming to South Blitar, she had been hiding in Surabaya, where she had moved houses regularly and eked out a meagre existence, relying on donations of money and food that were then pooled together with six other women. Lestari went to South Blitar to be reunited with her husband Suwandi, the East Java provincial secretary of the PKI. Journalist Lies Katno came in search of her husband, Pemuda Rakyat leader Sukatno. Winata, an engineer trained in Bulgaria, had been released from Salemba Prison in Jakarta at the end of 1966 but felt that his village was less safe than the capital. Scared of being rearrested and killed, he went to South Blitar to hide. There, these fugitives felt a sense of relative freedom and lived with local families, working in the fields, looking after farm animals and helping with household chores.

There is still controversy about the PKI's agenda in South Blitar. Some have portrayed the party remnants as planning to shift to peasant-based revolutionary war according to a Maoist model, while others have argued that the party members simply sought sanctuary from persecution by the Indonesian army and its allies. While it is true that remaining leaders no longer believed that it was possible for the PKI to take power peacefully, Rewang, then a member of the PKI Politburo, has argued that the possibility of organised, armed resistance was negligible after 1966.

The party's activities in South Blitar, however, soon came to the attention of anti-communist forces, and the perception grew that 'PKI remnants' were trying to rebuild. By 1967, the villages of South Blitar were divided as militias of the Islamic youth organisation, Ansor, affiliated with the conservative Nahdlatul Ulama, conducted more and more raids. During this period, Rewang recalls, efforts to regroup the party were limited to finding and meeting with former party activists, and the tasks of gathering weapons and ammunition and training guerrilla forces proceeed slowly. At the time of the Trisula Operation in mid-1968, they had only managed to organise one detachment of young men to train. Certainly this was no match for the thousands of soldiers deployed during Trisula, the counterinsurgency operation carried out between June and August 1968.

Intimidation and murder

According to army figures supplied to the New York Times, 5000 army personnel from six battalions, backed by the Strategic Reserve Command armour units and commandos, were involved in the Trisula Operation assisted by 3000 vigilantes armed with bamboo spears.

When the military arrived, soldiers sidelined the civilian defence guards accused of passing on information about military movements to PKI members and installed military personnel in place of village leaders suspected of having sympathies with the PKI. The soldiers then isolated the PKI fugitives from villagers by drafting locals into joint patrols, enforcing night curfews and, in the military's words, 'fostering hatred of the communists'. As locals understood the terrain better than the military, they were forced to participate in so-called 'fence-of-legs' patrols to flush out fugitives in the forests. In this strategy, local people formed a human chain under military supervision, moving across the landscape so that fugitives had no chance of slipping past military personnel. The army also made local men dig mass graves and later cover them over once transported prisoners had been shot.

The military forced villagers who were under suspicion of leftist sympathies to prove themselves by taking part in the killings. These suspects were forced to hit prisoners on the back of the head with iron bars and to plunge them into deep vertical caves such as Luweng Tikus (Rat Hole). For example, Oloan Hutapea, former member of the PKI Politburo, was killed when a villager called Slamet smashed his skull with a rock during military patrols on 21 July 1968. Slamet was lauded publicly at a ceremony in Lodoyo, the centre of the operations. His photograph is still on display today at the Brawijaya Museum in Malang.

Whole villages were then evacuated so that local people were no longer able to support those on the run or in hiding. On 23 June 1968, Infantry Unit 511 placed thousands of locals in holding camps in Sukorejo and Maron villages. A woman from Ngrejo village recounted that in August 1968 recordings of torture were played and amplified in order to intimidate the thousands of evacuated villagers gathered in Bakung subdistrict centre. The refugees had been told to bring their own food provisions, but many could not do so and dug up and ate a field of sweet potatoes nearby. The woman from Ngrejo recalled that some returned to their villages for supplies only to be shot by the occupying military forces.

By late 1966, PKI leaders on the run had few places to hide or people to turn to for support

After these killings, the fugitives tried to escape westwards towards Tulungagung subdistrict, through the forests on the south coast. Deciding to flee into the forest, Lestari left her months-old baby with a local villager whose own child had recently died. As the patrols came closer, the villager became so scared that she abandoned the baby at the entrance of the local cemetery and hoped someone else would look after her. Many fugitives hid in the teak forests near the villages. To intensify the pressure, military intelligence directed people to pull out any edible plants in and around the forests so the fugitives would starve. The New York Times article published on 11 August 1968 cited a figure, most likely supplied by the army, of 2000 'party members' killed or arrested over the preceding four months.

The 'rehabilitation' phase that followed the operation changed South Blitar in many ways. Military caretaker village leaders stayed on. To enable greater patrol and surveillance of the area, the East Java local government built new roads to open up the region, which villagers were forced to use when the government prohibited the use of local roads and shortcuts. Villages were redesigned, with houses and their inhabitants brought closer to the main roads. Land close to main roads was seized to house several families, causing chaos in land tenure. Part of the government's thinking was that some improvements to the people's lives were badly needed to avoid them falling prey to communist ideology. To this end, schools, mosques and other prayer houses were built for education and 'spiritual guidance'. Alongside this, however, was greater surveillance over their movements, and long-term sanctions for harbouring communists.

Moving on

Generations of villagers, particularly in remote areas of South Blitar, have suffered as a result of their association with the communists in the wake of the Trisula Operation. At the same time, however, they have drawn strength from their sense of shared grievance, from the feeling that what they experienced was not theirs alone, but something they have in common with others living in the area. For example, a woman who was sexually enslaved by her local village head said she was not an object of shame, because 'what happened to me was a common experience' in South Blitar.

Meanwhile, although visitor numbers to the Trisula Monument have declined, it continues both to commemorate the Suharto regime's version of history and to remind villagers of the brutal way in which they were treated. And until this day, the charge of armed insurrection against the Blitar PKI remains in force. But now at least the villagers and former political prisoners are able to tell their side of the story, and to an audience that is a little more receptive than before. Former political prisoner, Gerwani leader Putmainah, has spoken to the media and non-government organisations about her experiences and her arrest in South Blitar, while the Indonesian Social History Institute's Andre Liem conducted interviews in the area for an oral history project. In 2005 local youth in the Nahdlatul Ulama-linked organisation Lakpesdam collected testimonies about the impact of Trisula and they have tried to bring together informal gatherings of local villagers and NU leaders, as NU is still seen as a supporter of the military operations. These efforts represent small but important steps in confronting the Suharto regime's version of the past.

Vannessa Hearman (vhearman@unimelb.edu.au) is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne. Her research focuses on the politics of memory and history in East Java (1965-68).