Tristam Moeliono

Welcome to Dago PakarBlair Palmer |

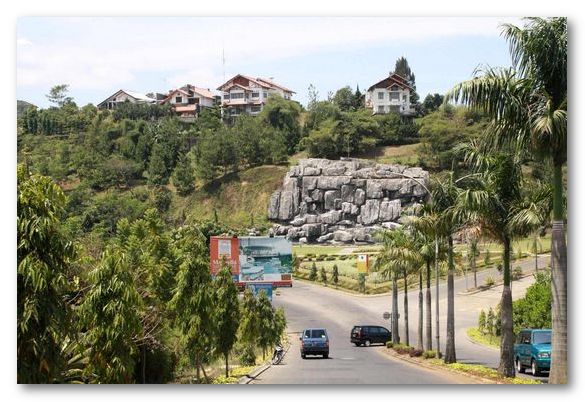

In the hills on the north side of Bandung, just outside city limits, a huge well-guarded gate marks the entrance to the ‘Dago Pakar Resort’ housing complex. A wall encircles the complex, separating it from the surrounding villages and lush valleys. Visitors wanting to pay a visit to one of the residents must enter through the main gate, then travel along the wide well-maintained roads past a number of smaller guard posts.

This is development for the rich. Even the smallest house costs approximately Rp600 million (A$85,000). Residents pay property tax to the local government, and also bear the costs of maintaining infrastructure and public services such as road repairs, clean water, garbage management, public safety, and the maintenance of parks. Dago Pakar has established an estate management body as a separate company to manage these services.

Apparently being designated as a protected area does not preclude development…Dago Pakar was built in the North Bandung conservation zone

There are hundreds of gated communities like Dago Pakar in Indonesia. What makes Dago Pakar different is that it was built in the North Bandung conservation zone, which is part of the administrative district of Bandung outside the municipality itself. This area serves as a water catchment area affecting the micro-climate of the whole Bandung basin.

In the protection zone

|

These roads don’t have potholesBlair Palmer |

There were only a few agricultural villages in the area until the 1980s. But then everything changed. In the late 1980s the district of Bandung decided to allow development in the conservation zone, which it considered under-utilised. Apparently, being designated as a protected area does not in fact preclude development in an area – it just means there should be stricter monitoring of development and land use there.

In the 1990s a private developer, Bandung Pakar, acquired permits for the exclusive right to buy up land from local communities and develop Dago Pakar as an integrated tourism area, mixing residential pockets with hotels, restaurants and other amenities, such as a golf course. These permits act as a sort of build-operate transfer agreement made between the developer and the district government. Within the development area, key district government responsibilities are transferred to the developer, including responsibilities to construct and maintain public roads, parks and open green spaces, and to regulate the land-to-building ratio of all properties. The developer also bears responsibility if the development results in environmental degradation.

The developer had to commit to set aside land for artificial lakes…but no lake has yet been spotted

Besides receiving payments for the permits, the district government also enjoys increased property tax revenue from the development. However, no mechanisms to ensure that people are treated fairly and the environment is protected are built into the Dago Pakar arrangement. In effect, the developer can avoid these responsibilities while maximising profits, handing over maintenance duties to the separate estate management company.

Displacing people and green spaces

|

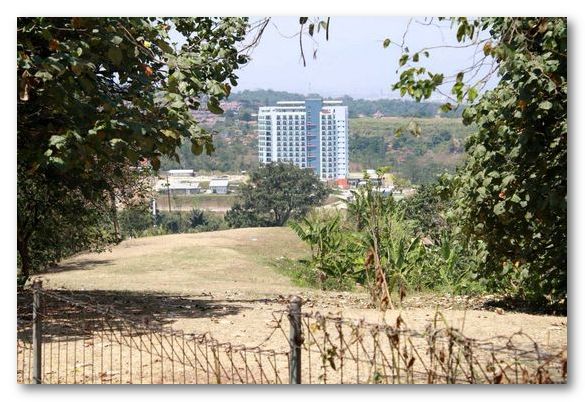

New tower in the protected zoneBlair Palmer |

Forested land containing three or four agricultural villages has now been replaced by the 320 hectare Dago Pakar complex. A number of specific environmental clauses were included in the agreement. But to meet the required minimum amount of green space to be reserved in the protected area, the developer constructed a golf course. In order to preserve the area’s water catchment capacity, the developer had to commit to set aside land for artificial lakes. But no lake has yet been spotted, despite ongoing campaigning from an environmentally-minded resident.

The district head can require permit holders to build public schools or roads for local communities, but this did not happen in Dago Pakar. Instead, the permits required that the developer fulfil its ‘corporate social responsibility’ by building a public meeting hall or a residence for district government officials within the complex.

The negative social effects of the development seem to have escaped the attention of district officials and of the public. Several villages within the area were displaced by the developer. Some of the displaced people moved to adjacent villages, while others moved into Bandung city or further afield. A few of those who did not move far have managed to obtain positions at Dago Pakar as guards or in other menial jobs. Some women have found employment as domestic workers in the complex, and some men pick up work as ojek (motorcycle taxi) drivers in the resort where there is no public transportation. It is likely that many others lost their livelihoods when they were displaced.

The resort poses a long-term threat to local people’s welfare through degradation of the environment

But nobody seems to know or care about the whereabouts of the displaced villages. In contrast to land acquisition by the government, for which data on displacement must be compiled, there are no reporting requirements about what happens to displaced land owners when their land is bought up by private developers. The company’s responsibility to them ends once it pays compensation. And when things go wrong, it is in practice nearly impossible for affected local communities to hold private companies accountable.

Estate permits must be reviewed

The development of Dago Pakar calls into question the whole rationale for granting such luxury estate permits. Government land use planning documents suggest that the Bandung district government sees its primary task as bringing development to local communities. It is clear, however, that the granting of permission for the establishment of Dago Pakar resort within a protected area has not benefited local people, and that it also poses a long-term threat to their welfare through degradation of the environment. ii

Tristam Moeliono (tristam_m@yahoo.com) is a lecturer in the Faculty of Law at Parahyangan University in Bandung and a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Law, Leiden University.