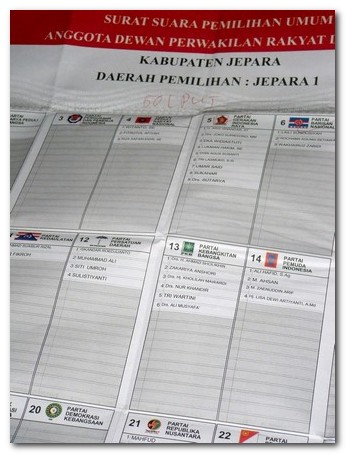

Weak rules and weak implementation meant that influence could still be bought in the 2009 elections

Indonesia Corruption Watch

Rules about how parties obtain funds, and how they use these funds, are a key part of ensuring fairness during elections – fairness between parties, and fairness to voters. Without these rules, older, better-established and more powerful parties could have unfair advantages in obtaining funds or in influencing voters. Without effective monitoring of campaign funds, parties can obtain funds from illegal sources, compromising future decision-making if they win power, and spend funds in illegal ways, such as by buying votes.

Unfortunately, in the 2009 legislative elections, the rules were so weak, and the implementation fell so far short, that in practice there was no real or effective monitoring of campaign funds. Parties were basically free to do as they liked, as long as they provided a very simple summary to the General Elections Commission (KPU), which has so far failed to check these reports in any significant way.

KPU working late

A main cause of this situation was that KPU was very late in issuing the regulations on campaign finance, and the regulations were unclear. The 2008 Election Law required the KPU to issue regulations on the recording of contributions, the reporting of funds obtained and spent, and the auditing of these reports. The official campaign period began in July 2008, but KPU did not issue the relevant regulation, KPU Regulation 1 of 2009, until February 2009, two months before the election.

Regulation 1/2009 stated that by 9 March, all parties, plus all candidates for the DPD (Regional Representatives Council), had to submit an ‘initial report’ and a campaign funds account number to KPU. It was not made clear, however, what this ‘initial report’ should contain. In the end, after much pushing from KPU, all parties submitted reports, by midnight on 9 March, but these reports were so minimal that in practice they did not enable the reports to play any useful role in guaranteeing a fair election or in punishing those who broke the rules.

The reports generally included only the account number in which the party supposedly kept its campaign funds, and the opening balance. They did not systemically report where those funds came from, whether the account was a personal or party account, or whether the balance was before or after spending funds on campaign costs. Some parties reported ‘initial balances’ of 5-15 billion rupiah (A$700,000 – $2.1 million), while others reported amounts as little as one million rupiah (A$140).

Lack of transparency

In contrast, rules about the ‘final report’ were clear, and the sanctions for failing to submit them were tough. KPU Regulation 1 of 2009 specified that parties and DPD candidates must submit a ‘final report’ of campaign funds by 24 April, 15 days after the legislative elections. This report was supposed to cover all campaign finance transactions between 10 July 2008 and 17 April 2009, including funds used throughout the country at all levels of the election (national, province, and district), and report on all donations, campaign expenses, and the final balance of the campaign account. Failing to submit these reports could result in a party losing its seats in parliament, according to the 2008 Election Law.

Procedures concerning campaign funds are all just an empty formality

After the deadline passed, KPU announced that all parties had submitted reports, but did not release any information about the contents of the reports, instead saying that the parties had submitted the reports directly to the external auditor. In early June results of the audits were posted on the KPU website, but the original campaign finance reports were still not released. The sense we get is that KPU and the parties have agreed together not to be strict in monitoring campaign finances. The result is that the procedures concerning campaign funds are all just an empty formality, and do not result in any real transparency or accountability.

As in past elections these audits seem to have been at best perfunctory, as only a ‘general’ audit was requested, not an ‘investigative’ audit. This means that the auditor would merely check the report to see if it contained any glaring errors, and not verify a sample of the donors listed in the report. Neither KPU nor the auditors seem to be interested in verifying whether all campaign donations and expenditures went through the official accounts. In fact it is likely that for most parties, far more was spent on campaigns than was reported.

To check the accuracy of the reports, we focused on expenditures, since it is much harder to find alternate data on campaign donations. AGB Nielsen, a research company, had recorded information on political advertisements since the beginning of the campaign figures. According to the data from AGB Nielsen, it appears that what parties spent on media campaigns was several times higher than what they reported to the KPU, in some cases more than ten times higher, for at least six of the nine parties winning seats in the DPR. If parties spent much more than was reported, then the sources of those extra funds are unknown to the public. The public needs to know who contributed to party campaigns in order to monitor whether elected leaders attempt to repay this support by means of policy decisions which are detrimental to the general public.

Candidates beneath the radar

The December 2008 decision by the Constitutional Court that the number of votes that each individual candidate won, rather than their position on a party list, would determine which candidates won a party’s seats, was a huge shock to many candidates. It meant that many individual candidates had to actually campaign for votes instead of winning election by being high up on the party list. This decision had impacts on campaign finances also. Now that candidates from a single party had to compete with each other for votes, they had incentives to spend their own money on their campaigns.

The public needs to know who contributed to party campaigns in order to monitor whether elected leaders attempt to repay this support by policy decisions which are detrimental to the general public

The result was that in many cases, candidates invested significant funds, either from their personal wealth or on loan from backers, in order to attempt to get more votes than other candidates from their own party and win election. However, since the 2008 Election Law stipulated that participants in the election were only parties and DPD candidates, individual candidates for election in the regional and national parliaments had no responsibility whatsoever to report their campaign expenditures.

Technically, all of their expenditures should come from the party’s official bank account, but in practice candidates obtained funds and used them however they wished. This means that the Indonesian public knows nothing about the financial backing behind the members of parliaments who will lead the country. These leaders may attempt to repay such backing using their government office, through corrupt allocation of funds or nepotistic appointments, and the lack of knowledge about the sources of funding will make such behaviour more difficult to prevent.

The public also knows nothing about how individual candidates spent their campaign funds. One of the ways candidates chose to attempt to influence voters was by paying them cash, or by distributing packages of goods to them (such as rice, sarongs, or other daily needs). Our network discovered 150 such cases, with the majority involving cash payments, usually distributed by candidates rather than party officials or success teams. Of course, such cases are rarely reported, and the reality is that attempts to bribe voters occurred often, and in most parts of the country, in this election.

The public knows nothing about the political debts owed by parties and legislators

The overall conclusion is that the regulations were issued late, they were unclear, and even when they were clear they were not implemented effectively. This means that there was effectively no real transparency and accountability regarding campaign funds in this year’s legislative elections. This weakened the fairness of the election. It also means that for the future, the public does not know anything about the political debts owed by parties and legislators. Those debts may influence policy decisions as well as heightening the risk of corruption as parliamentarians and party bosses draw on public money to pay back the people who supported their election bids or to recoup their own huge outlays of personal wealth. ii

This article was based on the report ‘Corruption in the 2009 Legislative Election’ by Indonesia Corruption Watch, and an interview with Adnan Topan Husodo (of Indonesia Corruption Watch) by Blair Palmer, an editor for Inside Indonesia.4