James Scambary

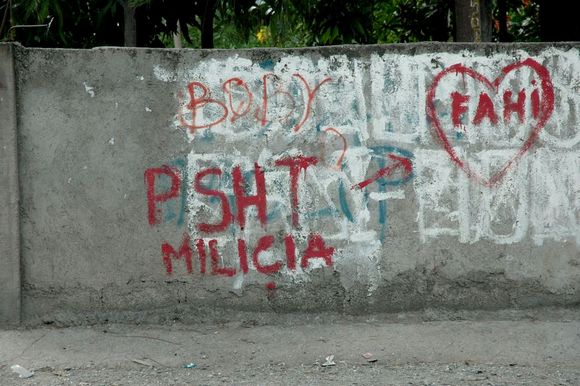

Graffiti on a wall in Dili that links the martial arts group ‘PSHT’ with the militiaJames Scambary |

The legacy of the Indonesian occupation is commonly depicted as the profound collective and individual trauma caused by the atrocities of the occupation, a trauma compounded by the lack of justice for the victims. Although many still fight for the perpetrators to be brought to justice, the occupation is spoken of as something that is in the past, something that finished with the departure of the Indonesian troops and their proxies in 1999. But while the Indonesian army and the militias may have retreated back across the border, they left behind the volatile, living legacy of a deeply militarised society with multiple, highly organised militant groups.

Since independence martial arts groups have become an entrenched feature of Timorese society

Poverty and recent political insecurity in East Timor have contributed to the presence of gangs in East Timor. However, they would not have achieved their current scale and level of organisation if not for the Indonesian occupation. Although these groups only recently gained international notoriety for their violence during the intense communal conflict of 2006-2007, their rivalry has plagued East Timor for most of the independence period.

Paramilitary and youth groups

The Indonesian military’s organisation of East Timorese into a range of formal and informal paramilitary groups as a counterinsurgency tactic is well chronicled in such documents as the report published by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2005. These groupings were widespread during the occupation years, and by the 1980s they numbered as many as 40,000 people. The groups ranged from the black clad ‘ninja’ gangs who roamed the streets at night terrorising independence supporters, to the militias whose post 1999 referendum campaign of terror resulted in over 1500 deaths and the displacement of over half of the population.

Another strategy of the Indonesian military was to socially engage East Timorese youth. By the 1980s youth had become an important element of the urban clandestine resistance, and the Indonesian authorities sought to indoctrinate or co-opt them by creating a variety of youth organisations. This was a tactic already tested in other parts of Indonesia, where the military gained access to gangs by establishing teen clubs that emphasised sports. Under this policy, the Indonesian military fostered hundreds of ‘youth groups’ in East Timor. The army supplied them with sporting equipment and organised competitions for them. Many of the hundreds of youth groups in Dili today were a product of this campaign.

Some contemporary gang members gained experience in gangs while living in Indonesia. In the mid 1980s to early 1990s the Indonesian military sent up to 600 Timorese youth to Indonesia for ‘training’. These youths were forced into slave labour conditions in factories or, in some cases, were forced to undergo military training at the Kopassus (Indonesian Army Special Forces) headquarters in West Java. Some of these youths went on to join gangs, most notably in the Blok M area of Jakarta. One Dili gang still bears the name ‘Blok M’ and is suspected to have continued links to the Jakarta underworld. A notorious Timorese underworld figure, Rosario Marcal aka Hercules, has re-emerged on the Timorese scene. Hercules used to be a private assistant of the Kopassus Commander, Major General Prabowo Subianto, in East Timor before he was sent to Jakarta in the early 1980s to organise pro-integration actions. The Indonesian military helped Hercules set up protection rackets and prostitution rings in Central Jakarta. After Hercules’ visit to Dili with a group of Indonesian businessmen in mid January 2008, there was intense speculation about his possible involvement in the assassination attempts on President Ramos Horta and Prime Minister Xanana Gusmao on 11 February 2008. There were subsequent calls from East Timorese authorities to widen the investigation into this event to include Hercules. Former members of Hercules’ gang are still active in Dili.

Martial arts groups

|

‘Slebor’ youth group members in their Dili clubhouseJames Scambary |

The most visible and problematic legacy of the Indonesian occupation are the martial arts groups. There are some 15-20 martial arts groups currently active in East Timor, dominated by the two largest groups Kmanek Oan Rai Klaran (KORK - Wise Children of the Land) and Persaudaraan Setia Hati Terate (PSHT - Faithful Fraternity of the Lotus). A World Bank report estimates that there are approximately 20,000 registered martial arts members and as many as 90,000 unregistered members. Several organisations have members in all 13 districts, with branches down to the village and hamlet level.

According to Dr Ian Wilson of Murdoch University, who has extensively researched martial arts groups in Indonesia, the New Order regime viewed sport, in this instance martial arts, as a tool of social control. As a consequence, the major Indonesian national martial arts associations had close links with - or were even established by - the Indonesian military. As an extension of this policy, Kopassus set up and trained martial arts groups in East Timor throughout the 1980s. This policy of organising Timorese youth into martial arts groups for the purposes of indoctrination is the main reason for the sheer size and variety of such groups today. Another significant influence on the growth of these groups was that being a member of one of the martial arts groups linked to the Indonesian military granted access to scholarships, jobs and, most importantly, protection from the military and militias.

After independence the martial arts groups continued to flourish and have become an entrenched feature of Timorese society. With continuing insecurity and the absence of a functional police force, these groups claim to provide protection for their members and their communities. However, in many cases they are the main cause of insecurity. Between 2000 and 2007, clashes between martial arts groups occurred in nearly all districts of East Timor, including Dili. The clashes were particularly endemic in the western highland regions of Ermera and Ainaro, and the eastern districts of Baucau and Viqueque. Conflict between these groups occurred with increasing intensity from 2004 onwards until the conflagration of 2006.

Groups that opposed occupation

Despite the best efforts of the Indonesian military to indoctrinate youth, a large number of groups were formed to oppose the occupation. In addition to the armed FALINTIL troops, there were countless cells of clandestine activists who supplied them with weapons, food, medicine and intelligence. Amongst these clandestine cells were the variously named ‘wound’ or ‘magic’ groups, most notably 5-5, 7-7 and Colimau 2000. In addition to these groups, in the mid-1980s, numerous small neighbourhood vigilante groups formed to alert their neighbourhoods of incursions by the Indonesian forces or their militias. In return for receiving early warning of attacks, community members would voluntarily provide these groups with payments of food or money.

Some groups such as 7-7 still define themselves as clandestine groups, even though the occupation is long past. Many of these groups have struggled to find a new role and identity in independent East Timor. Some have begun to hire themselves out as mobs or have become involved in petty extortion, gambling and organised crime. The groups often become a nuisance in their neighbourhoods due to drinking, violence and collecting a ‘tax’ from the community to fund themselves. Many people now give this ‘tax’ not out of support as they did during the resistance, but due to fear.

Old conflicts, new players

In some cases the groups have become a lightning rod for historic divisions. Villages which previously divided along pro- or anti-Portuguese lines, then pro-autonomy or pro-independence lines, now cleave along gang or martial arts group lines. It is not uncommon for an entire family or village to belong to the same martial arts group, and follow the same political party. As a result, communal conflicts that arise when communities use martial arts groups and gangs to attack another village tend to be glossed as martial arts conflicts or political conflicts. The mass scale of these groups, however, means that quite small family disputes can lead to a broader scale of conflict.

In some cases the groups have become a lightning rod for historic divisions

These fights are usually over unresolved disputes about land – another legacy of the Indonesian occupation. Most of these contemporary land disputes have their origin in the forced relocation and internal displacement that happened during the Indonesian era. Other land disputes originate in claims that a particular community or family collaborated with the Indonesians and that those people have therefore lost their rights to their land.

Accordingly, some conflicts are still fought along pro-autonomy and pro-independence lines, with some martial arts groups still being cast as pro-independence or pro-autonomy (even if those cast as being pro-autonomy, such as PSHT, may vigorously reject this tag themselves). In fact, in late 2006, a set of martial arts groups calling themselves the ‘originals’ formed a pact to fight the martial arts groups they saw as pro-Indonesian.

Uneasy future

It would be easy to say that with education and jobs these groups might fade away in the future, but this is unlikely. The Indonesian military’s systematic and comprehensive militarisation of East Timorese youth and the normalisation of violence through war will be felt in East Timorese society for some time. With little imminent prospect of a land dispute settlement regime, and a barely functioning justice system and police force, it is likely that people will continue to seek vigilante justice to resolve their disputes and to use gangs and martial arts groups as enforcers. ii

James Scambary is a journalist and researcher who has been researching gangs and youth culture for AusAID and other international agencies since 2006. He is the author of an AusAID report ‘A Survey of Gangs and Youth Groups in Dili, East Timor’ and a forthcoming report for the Geneva Small Arms Survey.