David Gutteling

This plaque is next to the Suai Convent Chapel where a massacre led by militias took place in 1999James Scambary |

The withdrawal of Indonesian forces from East Timor following the violent weeks of 1999 posed many challenges to the two neighbours, not least in relation to the question of border management. In some instances, the new international border resulted in villages and extended families being split between the two territories, interfering with communal trade and cultural practice. Following the arrival of the United Nations military intervention in September 1999, many of the militias fled to West Timor or based themselves in the border region. Villagers living along the border feared that the militias responsible for much of the rampaging, looting and killing would cause renewed violence and their presence raised concerns about retribution amongst the 250,000 East Timorese who were forcibly relocated to refugee camps in West Timor. Ten years later these issues continue to plague those managing the border region.

Border challenges

In 2001 a Joint Border Committee was created by East Timor and Indonesia to begin negotiations about border demarcation. These talks started positively but real progress has been slow for the last few years. The main dispute concerns the question of whether or not the new border should be defined by a Dutch-Portuguese treaty made in 1904 and which had remained in force until 1974. The East Timorese government wishes to retain the former boundaries, while the Indonesian leadership argues that local customary settlement (adat) has shifted the border and that new border arrangements should take this into consideration. To date 97 per cent of the land border has been demarcated, with the remaining 3 per cent to be decided in the first few months of 2009.

The new land border between Indonesia and East Timor has caused difficulties both for villagers living in its vicinity and for the border patrols guarding it. During the occupation, people could freely cross the border, but with the new international border in place, trade between villages on both sides has become problematic. Visits to extended family, which are an important part of Timorese communal life, have likewise become difficult. The border is 316 kilometres long but it has only four official crossing points. To get to a crossing, people need to travel long distances and when they reach a border post, they need passports and visas, which are hard to come by and so expensive that most people cannot afford them.

The new land border between Indonesia and East Timor has caused difficulties both for villagers living in its vicinity and for the border patrols guarding it

The barriers obstructing movement across the border have reduced trade between villages and forced some parts of East Timor to rely on the illegal border crossings to access goods. This is especially the case in the Oecussi enclave, one of the poorest areas in Timor, where even basic goods are much more expensive than in villages just over the border in West Timor. As a result, smuggling and other illegal border crossings have become top security issues for both countries. Another concern is the potential health risk associated with the hidden border crossings. For example, in 2008 it was feared that chickens infected with avian flu were being transported across the border from Indonesia. As it turned out the chickens were not infected, but officials say that because of the porous border it is only a matter of time before an outbreak of the avian flu occurs in East Timor.

The refugees living near the border also represent a problem for both countries. Of the 250,000 East Timorese who fled the violence in 1999 most returned home in the first few years, though some stayed in West Timor. Ten years on, almost 5000 people are still living in abysmal conditions in three refugee camps near the border in West Timor. One of these camps, Noulbaki, is a 15 minute drive from the capital of West Timor, Kupang, a prosperous port city with a population of 300,000. The refugees are undernourished and poor. They have almost no access to clean water and illnesses like malaria and dengue fever are widespread. The Indonesian government wants to close the camps and relocate the refugees, stating that they are now ‘new residents’. Jakarta discourages aid from non-governmental organisations, because it is believed that giving aid to the refugees would prolong their stay. Some former refugees have relocated to other areas in West Timor, where they work for a small salary farming corn and cassava, which is only a small step up from the poor conditions of the refugee camps. Over time, the owners of the land on which the refugees live have become less tolerant of their presence. When the refugees first arrived, the Indonesian government declared that they would stay only a short while. Now, almost ten years later, the original owners want their land back. While these tensions have not resulted in violence they have led to angry disputes between refugees and landowners who want the refugees to go back to East Timor. However, for most of the refugees, returning to East Timor is not an option. Some who had sided with Indonesia fear retribution from their neighbours while others think there is nothing left for them to return to.

Almost 5000 people are still living in abysmal conditions in three refugee camps near the border in West Timor

Finally, the retreat of the pro-Indonesia militias to the border region and into West Timor in 1999 did not completely end militia activities. Estimates from the UN suggest that as of 2005 almost 3000 refugees in camps were former militia members unable to return home because they feared they would be killed by vengeful East Timorese. Some of these militias intimidated other refugees and crossed the border into East Timor, causing instability. For example, in January 2006 three former militiamen were killed by Timorese border patrolmen in the district of Bobonaro and several others were arrested. It is unclear why the men were shot. The East Timorese said that they were former militia who had attacked the border patrol while the Indonesians said that the men had been fishing and had been shot without warning.

Managing the border

|

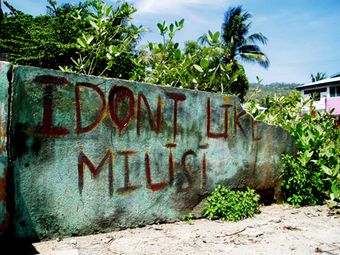

Graffiti on a wall in Liquisa, a town on the western side of East TimorChris Parkinson |

Efforts have been made by both Indonesian and Timorese authorities to manage the border. During the first few years after the referendum, border patrolling in East Timor was primarily carried out by UN forces. The UN also played an important role in establishing, training and advising the East Timorese Border Patrol Unit (BPU), which forms part of the East Timorese police force. After 2002 the UN gradually withdrew its soldiers, giving the East Timorese more responsibility.

The BPU and the UN met regularly with their Indonesian counterparts to talk about what should be done about the militias, smuggling operations and other illegal border crossings. From 2005 the BPU became solely responsible for East Timor side of the border. With only about 300 personnel they were spread thinly. In West Timor the border was defended by a battalion of the Indonesian army. Their task was perhaps more difficult than that of their counterparts since most incursions across the border would come from the Indonesian side. Although smuggled goods travel in both directions across the border, significantly more goods come from Indonesia and move into East Timor where they are sold for a larger profit. Petrol bought in Indonesia, for example, can be sold over the border in East Timor for a 30 per cent profit.

There have been a number of proposals put forward about how to improve border management in the area. The Truth and Friendship Commission report proposed that a ‘peace zone’ be built in the border region to enable official meetings between Indonesians and East Timorese. The report also suggested setting up joint patrols, watch posts and training programs as a means of improving relations between border patrols. Another possible arrangement is a soft-border regime, which will allow people without passports or visas to cross the border in more places. This is essential for traders and others who need to move frequently between East and West Timor. In 2006 the International Crisis Group recommended deploying more police, building better roads so that the border patrols can move along the border more easily and improving cooperation between countries.

For the time being, however, there are many aspects of the border region which are still unresolved. The situation of the refugees remains a poignant reminder of the violent events of 1999 and illegal border crossings continue to be one of the greatest security problems currently facing East Timor. Addressing these issues requires the continuing political will and cooperation of both governments. ii

David Gutteling (d.gutteling@gmail.com) is a graduate of Utrecht University where he received his master’s degree in history in July 2008. His masters thesis considers whether or not the United Nations interventions and state-building efforts in East Timor were successful. He is currently studying political science at the University of Amsterdam.