Damai Sukmana

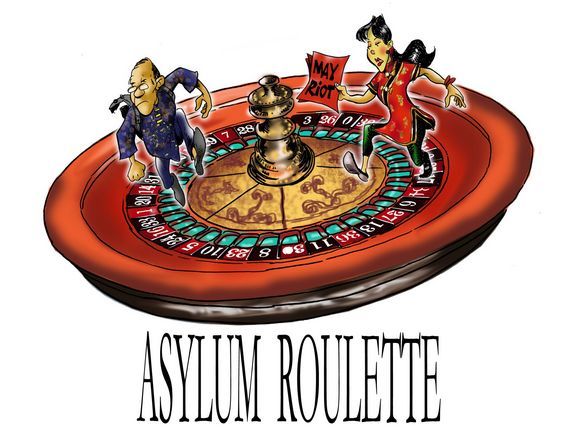

‘Asylum Roulette’dargos |

Ten years after winning his asylum interview, Victor Liem (not his real name) is now a permanent resident of the US and one step away from becoming a US citizen. Despite the improved situation for ethnic Chinese in Indonesia, Liem – who has built and runs his own business in Silicon Valley – and his wife still feel nervous about returning. In the 1990s Liem was a hopeful businessman in Jakarta. He was a London School of Engineering graduate and owned two companies in West Jakarta. On 14 May 1998, driving home along the Kebon Jeruk highway, Liem was confronted by an angry mob attacking motorists with rocks, wooden bats and metal bars. The thugs were checking motorists’ identity cards. He saw light skin-coloured men being dragged from their cars and beaten. Liem made the decision to drive at high speed through the makeshift blockage rather than risk being stopped. He finally reached Serpong Gate and was saved by locals who secured the area. His car was severely damaged by rocks. There were serious cuts on his face and hands. He then realised that a long sharp metal bar, which had broken the windscreen, had fallen just next to his stomach.

Liem and his family got the first available flight out of Indonesia. They landed in the United States in June 1998. The whole family applied for political asylum, and their application was approved soon after. Today there are at least 7000 Chinese Indonesians - former asylum seekers - living in United States.

Fleeing after May 1998

Thousands of Chinese Indonesians left Indonesia after the anti-Chinese violence in Jakarta and other major Indonesian cities in May 1998. Many fled to the US seeking sanctuary either temporarily or with the hope of permanent settlement. Indonesia is currently one of the top 25 countries whose citizens seek asylum in the United States, peaking at 12th ranking in 2004. According to the US Department of Justice, over twenty thousand Indonesian asylum cases have been filed since 1998. In 1998 alone, at least 1972 Indonesians were granted asylum in the United States; the highest number granted for Indonesians as a result of the relatively fast and non-adversarial process of ‘affirmative asylum interviews’, in a decade. The majority of these political asylum seekers from Indonesia were of ethnic Chinese descent.

Thousands of Chinese Indonesians left Indonesia after the anti-Chinese violence in May 1998

This unusually high number of successful asylum applicants was greatly influenced by considerable and high-profile lobbying on their behalf by Chinese American groups. In the wake of the May riots members of the ethnic Chinese diaspora, particularly those in the United States, were outraged at the targeting of ethnic Chinese Indonesians and lobbied their own governments to condemn the inaction of the Indonesian government to protect them. Those approached by Chinese American groups included high profile politicians such as the present Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, and Gavin Newsom, currently Mayor of San Francisco. Liem and his family were beneficiaries of this effort. But as the political heat around this issue cooled, so too did the relative ease with which asylum applications were granted. Now Chinese Indonesians whose claims are yet to be resolved face a game of asylum roulette.

Asylum roulette

In the ten years to 2007, 7359 asylum cases involving Chinese Indonesians were approved and 5848 cases denied. Chinese Indonesians commonly relate their asylum claims to the history of government-sponsored discrimination, persecution and violence towards the minority. While many may not have experienced personal physical harm, they have feared persecution in the past, and now fear present and possibly future persecution.

A decade after the May riots and despite important changes in law and the lack of anti-Chinese violence in this time, Chinese Indonesians continue to seek asylum overseas because they fear persecution. Many continue to suffer trauma as a consequence of events in the past and maintain a continued sense of vulnerability about their situation in Indonesia, seeing these legal changes as simply cosmetic. Recent arrivals to the United States indicate that they simply do not trust the government to provide them with the protection they will need in a time of potential future crisis and targeting of ethnic Chinese. Although, all hope that these new legal and cultural freedoms will help more ethnic Chinese feel safe at home, and when they don’t, asylum should always be an option.

Proving a credible fear of persecution is crucial to winning an asylum case. As the political system in Indonesia and the legal conditions for ethnic Chinese have improved, including the repeal of discriminatory legislation in recent years, proving such a fear has become less straightforward than it was in 1998. Moreover, in recent times applicants have found the asylum seeking process to be considerably more difficult. If their application is denied at the first hurdle by the Asylum office, an applicant’s case is then referred to an Immigration Judge. This process is usually called a Defensive Asylum Hearing and applicants must find legal representation. If they lose their case before the Immigration Court they may then appeal at the Board of Immigration Appeal (BIA) and Circuit Courts.

The lives of Chinese Indonesians currently in the US with asylum cases still pending in the Courts remain in limbo

The lives of Chinese Indonesians currently in the US with asylum cases still pending in the Courts remain in limbo. For many years now they have counted the days until the US Circuit Courts issue the final order for them to, in all probability, leave the country. Some are even detained for immigration violations before being deported. Outcomes depend on how individual judges interpret the case, how convincingly an applicant’s story is presented to the court, if they can afford or find pro-bono counsel willing to provide representation, as well as the standard of such representation.

However, an important and relatively recent precedent for these later Chinese Indonesian asylum cases is that of Sael vs Ashcroft, decided in October 2004 by the Ninth Circuit Court. This court covers many states, including California, Washington, Oregon, Nevada and Hawaii. It is the largest circuit court in the United States and overall second only in size to the US Supreme Court. The Court ruled that Taty Sael and her husband were eligible for political asylum after finding that the woman faced likely persecution in Indonesia. The US Court of Appeal gave three reasons for finding Taty would be in danger if she were deported. These were the historical pattern of anti-Chinese violence that dates back to 1740, laws still on the books that prohibit Chinese schools and other institutions, and mob attacks and threats against the applicant before she fled with her husband. Her husband’s asylum claim was based on her situation.

This marks the first time a US Court has ruled there to be government-sanctioned discrimination against Indonesia’s Chinese minority. Despite this precedent however, many Chinese Indonesian asylum seekers still face challenging legal battles in US immigration courts. Those who lose face the reality of returning to Indonesia. ii

Damai Sukmana (damaisukmana@gmail.com ) is the pseudonym of a Chinese Indonesian former asylum seeker, now living in California.