Two Chinese-Indonesian women are role models for the younger generation

Aimee Dawis

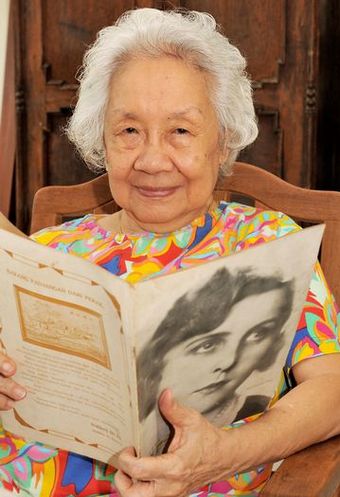

Myra SidhartaIBAS |

The spectacular influx of Chinese immigrants in the 1920s – caused by political turbulence in China after World War I – brought many Chinese women to Indonesia. Before that, the Chinese immigrants had been mostly men. In the early twentieth century, Chinese women’s primary tasks were to care for their husbands and offspring, and their social position was measured in relation to fathers, oldest brothers, husbands and sons. During this period, domestic skills such as sewing and cooking were highly regarded, as they made a young Chinese woman desirable to her prospective husband and his family.

However, some brilliant Chinese-Indonesian women have proven that they can succeed in their chosen professions despite limits on the educational and social opportunities available to Chinese women, which remained in force through much of the twentieth century. Myra Sidharta, one of the most prolific writers and researchers on Chinese-Indonesian culture and philosophy, is one of them. Melani Budianta, the first Chinese-Indonesian woman to become a Professor of the School of Humanities at the University of Indonesia, is another.

Preserver of Chinese Indonesian culture

Myra Sidharta is a third-generation Chinese-Indonesian, born on the island of Belitung to a family that valued Western education. As her grandfather and father worked for a Dutch mining company, she and her siblings were allowed to enroll at the small Dutch school run by the company. She soon acquired a good grasp of the Dutch language and culture through school and her father’s many Dutch magazines and books.

Despite her western education, Myra never forgot her Chinese roots. Like most Chinese on the island of Belitung, she spoke the Hakka dialect at home and with other Chinese. Through the help of a Mandarin teacher, who resided at her grandfather’s house, she learned how to speak Mandarin and write Chinese characters. Later on, she visited her grandfather’s hometown in Meixian, a journey she wrote about it in her essay, ‘In Search of My Ancestral Home’. Throughout her career, she wrote often on the multifaceted aspects of Chinese-Indonesian culture, from localised Chinese cuisine to a biography of Kho Ping Ho, a Chinese-Indonesian martial arts writer.

Despite her western education, Myra never forgot her Chinese roots

Myra’s life and career reflect the ways in which the Indonesian, Western and Chinese aspects of her heritage intersected to form a cultural identity that is uniquely hers. Even though she values her western education and Chinese culture, she regards herself as Indonesian first and foremost. She says that she feels happiest in Indonesia, the place where she works and feels most needed. She vows to never stop writing and researching because her work is one of the ways through which she can contribute to her country.

Scholar and activist

|

Melani BudiantaThe Jakarta Post/Ida I. Khouw |

Melani Budianta was born in the 1950s, when education was becoming more available for Chinese-Indonesian women. A seventh-generation Chinese-Indonesian, Melani rejected her ‘Chineseness’ while growing up, and still considers herself much more Indonesian than Chinese. She was born into a peranakan family, whose first language is Indonesian. Her family embraced indigenous arts and cultures, and as a child she learned Javanese dances and watched wayang orang performances.

Like Myra, Melani is a prolific writer and researcher. A scholar, educator and feminist activist, Melani observes that women are often seen as victims of patriarchy in their own cultures as well as by a racist state. Without negating the fact that such victimisation takes place, she firmly believes in the resilience of women as survivors, and as resourceful agents for peace-making and social change. She has a strong faith in Chinese-Indonesians and their role in the making of the nation. For Melani, cultural identity is fluid, multiple, and constantly in the making. She believes that Chinese-Indonesian women always have room for negotiating their identity, and for finding a niche. This leads her not to ask why Chinese-Indonesian women are not accepted, but rather how their long multicultural history can enrich Indonesia.

A seventh-generation Chinese-Indonesian, Melani rejected her ‘Chineseness’ while growing up, and still considers herself much more Indonesian than Chinese

Melani has written about the process of self-identification – how to deal with Chineseness – differs from one generation to another, and from one individual to another. She argues that the meaning of Chineseness shifts through time and place, and is dependent on the tug-of-war between self-positioning and being positioned by others. As post-1998 Indonesia moves into an environment that is more open and accepting of Chinese language and culture, Chinese-Indonesian women are presented with a host of new opportunities and challenges that will raise more questions about how they make sense of their identity as Chinese individuals in Indonesia.

Exceptional women

As post-1998 Indonesia moves into an environment that is more open and accepting of Chinese language and culture, Chinese-Indonesian women are presented with a host of new opportunities and challenges that will raise more questions about how they make sense of their identity as Chinese individuals in Indonesia.

Myra and Melani are two exceptional Chinese-Indonesian women with exemplary lives from which the younger generation can learn. In defiance of the limited educational and social opportunities available to Chinese-Indonesian women of their time, these two women have managed to realise their aspirations through their own abilities. By writing, researching and teaching about various topics ranging from Chinese-Indonesian culture and philosophy, feminism, cultural studies, multiculturalism and postcolonialism, the two women have shown that they can rise above society’s expectations. In going against the grain, they have become role models for the younger generation. ii

Aimee Dawis (canting@hotmail.com) teaches in the graduate programs of the University of Indonesia’s School of Social and Political Sciences, Department of Communications, and the Department of Letters at the School of Humanities.