Glodok: A photo essay

Monika Swasti Winarnita

In the wake of the riots in May 1998 and the revelation that more than one hundred rapes – mostly of Chinese Indonesian women – took place, sensationalised representations of this sexual violence emerged in some parts of Indonesian society. Pornographic novels and tabloid stories surfaced, depicting Chinese Indonesian women as exoticised, lascivious Orientals somehow deserving of the hate-filled violence unleashed upon them. Images were also circulated on the internet of a beaten naked woman’s body, upon which the words ‘Cina’ or ‘Chink’ were inscribed. Whether these were ‘real’ photos or manipulated is unknown and in some ways irrelevant. What was alarming was the way in which these women’s bodies were used as markers of cultural, ethnic, and racial difference.

The day after the May 1998 riots in Jakarta, photographic artist Paul Kadarisman took photos in Glodok, Jakarta’s Chinatown. Glodok was one of the worst hit areas of the city in the destruction that took place on 13 and 14 May. Its malls and markets were ransacked and severely damaged and the large Glodok Plaza mall set alight. In a pattern repeated elsewhere in Jakarta and other cities, urban poor looters from nearby slums perished in the fire. Kadarisman has previously exhibited works of photography that critically engage with social concerns but these Glodok images have not been exhibited.

I was invited by the photographer to write a commentary to accompany the photos – as it was put to me, a personal note about the event. As an Indonesian with a mother of Chinese (peranakan) descent and a Javanese father, the riots had a very deep and profound affect on me. Like the photographer, I write this commentary with the awareness that it is only a limited representation of the atrocities that took place. Both textually and visually, this is only a partial record of what took place.

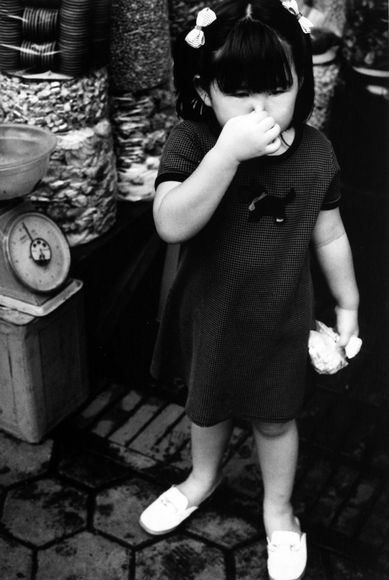

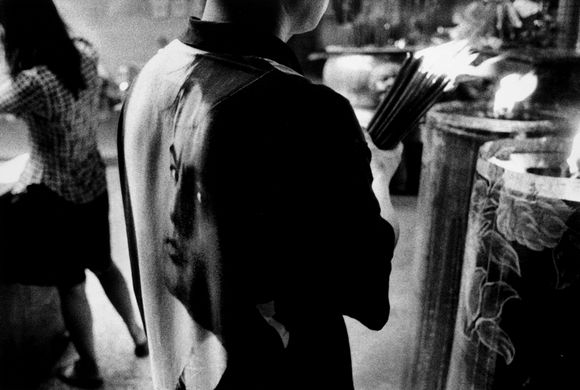

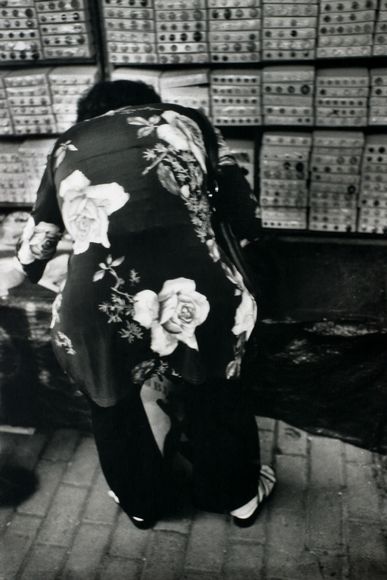

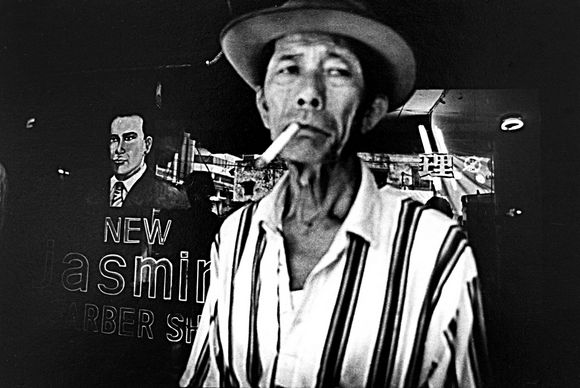

These photos are not intended to further the spectacle of violence. Through framing, choice of angle and composition, Paul Kadarisman conveys the atmosphere of fright and horror during and immediately after the May riots. However, he uses symbols and metaphors in his images without deliberately representing the ‘realities’.

As the photographer intended, the photographs should also speak for themselves.

Photos: Glodok, May 1998

Under the New Order, legislation outlawing the use of Chinese language and forms of cultural expression, including Chinese names, sought to encourage their assimilation as Indonesians. At the same time, the government acted to highlight their Chineseness in other ways, and as a group they remained outsiders conveniently marked by ethnic, religious and class differences.

|

|

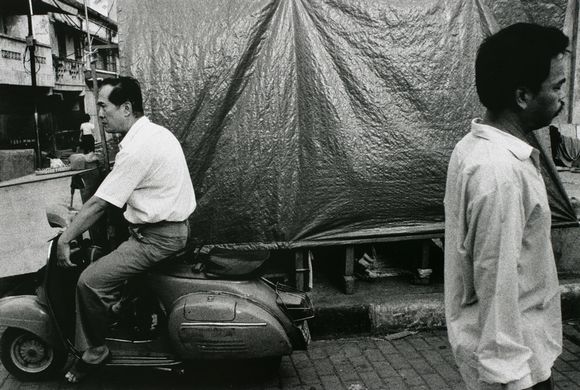

The sense of fear within this community in the aftermath of the May 1998 violence gave rise to deep suspicions and cleavages between this minority and their non-Chinese neighbours, long fuelled by government rhetoric and heightened during the economic crisis. This image gives a sense of the divide between these groups, widely interpreted to be the reason for the ‘mass’ anger towards ethnic Chinese. In the popular imagination, the ethnic Chinese were considered to be economically better off, favoured, corrupt, and somehow part of the cause of Indonesia’s economic misfortunes in the late 1990s.

|

This image of a black leather motorcycle glove lying on the gravel is most affecting in its simplicity. Our knowledge of the violence on the streets of Jakarta over those few days in mid-May 1998 informs our interpretation of it. The glove is tattered and battered – like those worn by motorcyclists who were dragged off their motorbikes and beaten before the bikes were burned.

|

The repeated use of the motorcycle in these images challenges stereotypes of Chinese Indonesians as an economically homogenous group who can afford to ride in cars, invisible behind dark tinted windows. They remind the viewer that Chinese Indonesians were visible and vulnerable to attack.

|

|

At the same time, most of the businesses damaged in the Glodok district were owned by Chinese Indonesians who, unlike the victims of the violence from the nearby slums, had the means to quickly set about making repairs and rebuilding. Glodok was one of the first areas in the city to rebuild.

|

|

Each year on the anniversary of the riots, victims/survivors’ groups and non-government organisations hold ceremonies to remember the victims of the violence. The victims and their families have so far not been given the opportunity to seek out the truth about these events. Ten years after the release of a fact-finding report into the riots, its recommendations have been rejected by successive governments. Repeated calls by the National Commission for Human Rights for the establishment of an ad hoc Human Rights Court to look into this case have also fallen on deaf ears.

|

As a textual and visual commemoration piece this article hopefully gives a glimpse into the atrocity of May 1998. It does not capture the full extent of the violence or the myriad of experiences of those involved. It is intended to be part of a continuing act of remembering, ten years on. ii

Monika Swasti Winarnita (u2588275@anu.edu.au) is currently an Honorary Research Fellow at the Monash Asia Institute and a PhD candidate at the Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. I would like to thank Alexander Supartono and Melani Budianta from the University of Indonesia for this article’s inspiration as well as getting me in touch with the photographer.

All of the photos in this essay are courtesy of Paul Kadarisman.