Juliette Koning

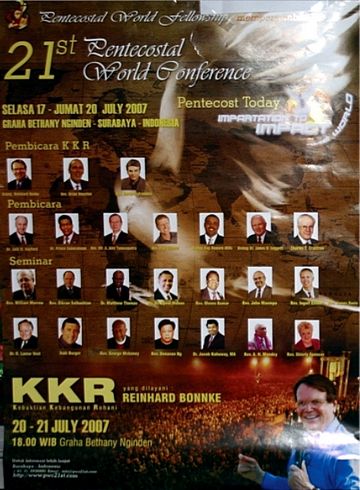

A flyer announcing the Pentecostal world conference meeting in SurabayaJuliette Koning |

It is an ordinary Sunday morning, around eight o’clock. Via the backdoor of a famous restaurant in Yogyakarta, and after three flights of stairs, stands a room containing a podium, a speaker’s stand, flowers, microphones, a PowerPoint screen, and a few hundred folding chairs. The sort of thing one can find at a multitude of events in Indonesia. Less common are the young people tuning their musical instruments, and the two men and two women softly swaying, microphones in hand, eyes closed.

A young woman walks up and down. Behind her, two female dancers in white-green robes are positioned, eyes closed, waiting. People flock into the room, and soon there are no seats left. A few minutes past eight-thirty the music begins to swell and the young woman starts to sing. After a few songs the congregation, led by the young woman, declares: ‘We love Jesus’, ‘Jesus is our Lord.’ Within minutes everyone is dancing, eyes closed and arms up high, as the music swells to rock-concert volume.

In itself there is nothing unique about this kind of worship. Meetings like this one occur in Pentecostal-charismatic churches and gatherings all over the world. The only difference lies in the scale and level of professionalism. Elsewhere in Asia, at well-known mega-churches such as the Yoido Full Gospel Church in Korea and the City Harvest church in Singapore, thousands of people gather to experience the Holy Spirit. In Indonesia’s overtly Muslim context, this Christian phenomenon takes place on a much smaller scale, although last September Jakarta witnessed the opening of an evangelical mega-church that attracts 4000 people each week. Perhaps most remarkably, the majority of the preachers, worship leaders, musicians and audiences are ethnic Chinese.

Conversion amidst crisis

Many of the Chinese Indonesians who are Christian are attracted by messages of personal confidence displayed by the charismatic movements. The enormous and growing popularity of charismatic Christianity among Chinese Indonesians raises questions about why Chinese Indonesians in particular have found their way to this religion.

Many of the Chinese Indonesians who are Christian are attracted by messages of personal confidence displayed by the charismatic movements.

Conversion is a personal experience. But it occurs within a social, political and institutional context. The reasons why so many Chinese Indonesians have converted therefore lie both in the inner meaning people find in the Pentecostal-charismatic movement and the circumstances in which the Chinese Indonesian minority find themselves within the Indonesian nation state. The end of the twentieth century was an extremely difficult period for all Indonesians, but especially for the Chinese. During and after the anti-Chinese violence that accompanied the end of Suharto’s long reign, many Chinese Indonesians left the country never to return. The fall of Suharto brought with it promises of change, as his New Order regime had been responsible for anti-Chinese rhetoric and practices carried out under its policy of assimilation since the mid-1960s. However, more than thirty years of New Order policies left their mark, and discrimination against Chinese Indonesians continues.

For many, religion offers peace of mind and feelings of safety in such times of trouble. But this does not explain why Chinese Indonesians might choose the Pentecostal-charismatic movement over other, more established community religions. For that, we must look to the particular character of the Pentecostal-charismatic movement itself.

A sense of belonging

|

A poster in a charismatic church in Yogya announces a worship meetingJuliette Koning |

The Pentecostal-charismatic movement, with its transnational fellowship networks, Internet prayer groups and extensive religious broadcasting, has a global outreach that creates feelings of belonging. The Born Again conversion experience in particular unites followers globally as people who have experienced the power of the Holy Spirit. Pentecostal-charismatic Christianity is also focused on issues and problems in congregations’ local contexts.

In the Yogyakarta restaurant, the first hour of ceremonies prepares people to receive the gifts of the Spirit, or to meet Jesus face-to-face by distracting them from their daily tasks, worries and busy lives. But in the second hour the preacher draws on the bible to address their everyday problems. As the preacher explained, ‘We make a connection to people’s daily lives; how can God help us to solve our problems and to be strong?’ Narratives about problems encountered and the experience of connecting to Jesus are told over and over again during the Sunday meeting. The audience listens carefully, and many nod approvingly, every now and then exclaiming halleluiah. These narratives, explicitly addressing business and family problems and everyday anxieties, are a defining feature of the charismatic movement, and are very important to its congregations.

These explicit and implicit messages of belonging, the opportunity to discuss everyday problems and messages of self-esteem and empowerment are deeply attractive to many Chinese Indonesians in what remains a potentially volatile and insecure environment. As a member of the congregation explained, ‘Many threatening things happen to Christian and business people in Indonesia. Their stores were burned to the ground in Solo and Jakarta. This and the crisis opened their eyes. They became aware that there is something above them that is bigger. They started to put their hope in Jesus. The charismatic movement was there to help.’ ii

Juliette Koning (JBM.Koning@fsw.vu.nl) is a senior lecturer in the Department of Culture, Organisation and Management at the VU University Amsterdam and the coordinator of the Southeast Asia program of the Faculty of Social Sciences.