Young Chinese Indonesian filmmakers examine questions of Chineseness

Charlotte Setijadi-Dunn

After more than three decades of suppression under the New Order, many Chinese Indonesians still find it difficult to let go of past fears and long-held beliefs about how one should ‘behave’ as a Chinese person in Indonesia. Signs are, however, that these attitudes may be starting to change. Especially among the younger generation; some Chinese Indonesians are now actively asking uncomfortable and often controversial questions about past injustices and what it means to be Chinese. One of the channels they are using to raise these questions is film.

Post-Suharto Indonesia cinema as a whole has enjoyed a revival since it became possible to address previously taboo topics. Beginning with Nia di Nata’s Ca-Bau-Kan (2002) and Riri Riza’s Gie (2005), film has increasingly become a medium where concerns about the position of Chinese Indonesians are being aired. In contrast to the New Order years, when Chinese Indonesians were almost completely absent from Indonesian cinema screens, in 2008 there were at least eight films of varying lengths that featured Chinese Indonesian characters or dealt with issues related to their community.

Defining ‘Chineseness’ through film

In this changing creative environment, a new breed of young Chinese Indonesian film directors, such as Edwin, Ariani Darmawan and Lucky Kuswandi, are using their filmmaking skills to explore issues of identity, past discrimination and other questions about being Chinese. For example, in May 2008 there was a Jakarta screening of short films from Proyek Payung (Umbrella Project), a project designed to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of the May 1998 reform movement. Four of the ten films screened raised Chinese Indonesian issues.

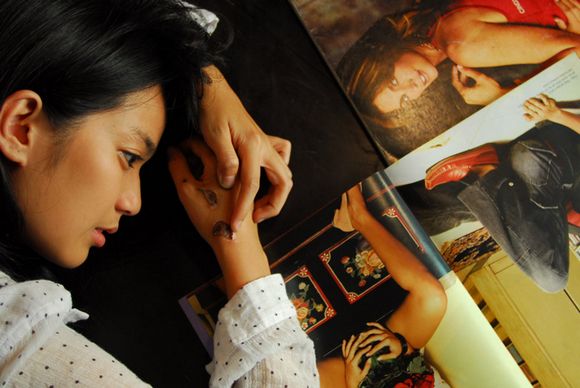

|

Still photo from ‘Babi Buta Yang Ingin Terbang’Edwin, Blindpig Films, 2008 |

Ariani Darmawan’s Sugiharti Halim (2008), Lucky Kuswandi’s Letter of Unprotected Memories (2008), Edwin’s Trip to the Wound (2008) and Ifa Isfansyah’s Huang Chen Guang (2008) all used the film project to re-visit some unanswered questions. For example, in Sugiharti Halim, Ariani Darmawan told the story of a young Chinese Indonesian woman (Sugiharti) who complains about the problems she has had over the years with her name. She insisted that her ‘Indonesian–sounding’ name given by her Chinese Indonesian parents does not suit her. The main theme of the story is of course inspired by the experiences of millions of Chinese who in 1966 were forced to change their Chinese names to ‘Indonesian-sounding’ ones in accordance with the same Cabinet Presidium No. 127/1966 that enforced assimilation. Other recent Chinese Indonesian-themed films include Steve Purba’s Kita Punya Bendera (2008), a children’s movie documenting a young boy’s journey to find out about his Chinese heritage, Viva Westi’s May (2008) that deals with the issues of the May 1998 rapes of Chinese women, and Allan Lunardi’s Karma (2008), a horror film centred around a Chinese Indonesian family’s traditions.

Lucky Kuswandi has said that directing Letter of Unprotected Memories gave him the opportunity to explore some personal questions regarding the significance of public recognition of Chineseness in recent years. The film, which explores the director’s own feelings of confusion and ambiguity every time Chinese New Year celebration comes around, talks about not being able to relate to his Chinese heritage. It is as though now that the Chinese are ‘free’ to ‘be Chinese’, he is expected to be able to connect with a Chinese culture that he knew very little about to begin with. He is certain many other Chinese also feel the same way. ‘It is weird for me that when Imlek comes along every year, all the memories of growing up in a time when Imlek was still forbidden come flooding back to me,’ Kuswandi said. ‘I don’t know all that much about my Chinese heritage and in a way, I don’t quite know how to feel about Imlek, nor do I understand how to act.’ Kuswandi added that he is certain that many other Chinese feel the same sense of ambiguity. He hopes that films such as his will encourage people to engage in further discussion about some of these rarely-explored subjects.

Edwin believes that films like his and Kuswandi’s are important because they are intended to help people ‘remember that these issues still exist, just like scars’

Trip to the Wound, a short film about a young woman’s ‘invisible’ scars and her encounter with a stranger who sits across the aisle from her on an overnight bus journey, also explores sensitive topics about trauma and unspoken pain. The young woman’s revelation to the stranger that she has an invisible scar that cannot be seen but can be felt, invites the audience to reflect upon traumatic events like May 1998 that are yet to be resolved. The director, Edwin, believes that films like his and Kuswandi’s are important because they are intended to help people ‘remember that these issues still exist, just like scars’. With this film and his new independent feature film titled Babi Buta Yang Ingin Terbang (The Blind Pig Who Wants to Fly, 2008) about the problematic lives of several intersecting Chinese Indonesian characters dealing with the stigmas associated with being Chinese, Edwin hopes not only to enrich the Indonesian film industry but also to contribute to the public discourse of Chineseness in Indonesia.

|

Still photo from ‘Babi Buta Yang Ingin Terbang’Edwin, Blindpig Films, 2008 |

Ambiguity, the desire to belong, and the ‘revisiting’ of old wounds raised in these films are issues that are often neglected in discussions regarding the Chinese in Indonesia. Nevertheless they continue to affect people’s lives, especially those of the younger generation, as they negotiate and construct their identities.

Alternative narratives of being Chinese

Some may be sceptical about the ability of cinema to make any ‘real’ impact on the lives of Chinese Indonesians. But at the very least films present alternative viewpoints on what it means to be Chinese – viewpoints that rarely surface in Chinese identity politics and public displays of multicultural harmony.

Films present alternative viewpoints on what it means to be Chinese

At a time when it is no longer taboo to speak of Chinese issues, these young directors are speaking up about their life experiences through their films. Their stories stand for those of so many other young Chinese whose voices are yet to be heard. If we want to better understand the complex issues of Chinese Indonesian identities and socio-political space in post-Suharto Indonesia, then listening to what these films have to say is a good place to start. ii

Charlotte Setijadi-Dunn (c.setijadi-dunn@latrobe.edu.au) is a PhD Candidate in Anthropology from La Trobe University. Her dissertation looks at historical memory and identity construction among young Chinese Indonesians in post-Suharto Indonesia.