Kipley Nink

Stefanus Akanmor (yellow shirt) carves the bisj-pole with chisel and hammerStefanus Akanmor |

In November 1961 Michael Rockefeller, son of the millionaire philanthropist Nelson Rockefeller, disappeared, presumed drowned, after his boat capsized at the mouth of the Betsj River in West Papua. Some of the material he collected on this, his second and final trip to the Asmat region, is now on display in a dedicated wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Among the most spectacular exhibits in the collection is a wall of nine bisj-poles, traditionally carved from the buttress of a mangrove tree to honour recently killed warriors in some Asmat communities. But, unlike Rockefeller, after whom this wing of the museum is named, the ancestors these poles commemorate are now nameless.

The Rockefeller exhibition is just one example of the way in which bisj-poles have become divorced from their original context and meaning. More recently, they have been reproduced by non-Asmat people to represent West Papuan and Indonesian art, appearing on T-shirts and key rings and in carvings at significant sites such as Jakarta’s Sukarno-Hatta airport. They have also been used outside Indonesia to promote tourism and cultural diplomacy.

Through the Peace Child Concert, Asmat art became explicitly linked with the asylum seekers’ campaign for independence in their homeland

But as Papuan refugees living in Australia have shown, bisj-poles can still have meaning for contemporary struggles. In March 2006, the 43 West Papuans who had arrived on the shores of Cape York in far north Queensland two months earlier were granted temporary protection visas by the Australian government. Two of the 43 asylum seekers, Alfons Pirimapun and Stefanus Akanmor, are Asmat carvers. In December 2006 they produced a bisj-pole for the ‘Peace Child Concert’, a festival at Federation Square in Melbourne that represented a collaboration between West Papuan and Japanese artists. Through the Concert, Asmat art became explicitly linked with the asylum seekers’ campaign for independence in their homeland.

Reclaiming cultural territory

|

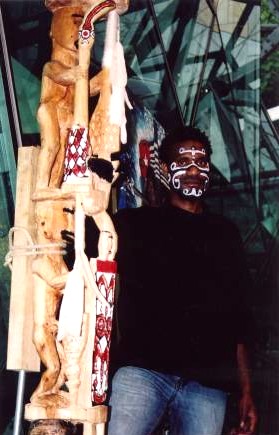

Stefanus Akanmor holds the completed bisj-pole carving

|

Why did the carvers make a bisj-pole? Why not a shield? Or a drum? When I asked Alfons and Stefanus this question, the two carvers looked puzzled. In some ways, the ubiquity of bisj-poles today – and their symbolic association with West Papua – makes it a clear choice. As Alfons replied, as though stating the obvious, ‘It’s popular’.

The composition of the bisj-pole produced in Melbourne echoes the traditional bisj-pole style. It consists of carved figures placed one on top of the other in black, red and white. But it is also unique. An obvious point of difference is the smaller size of the carving, which reaches to no more than three metres. In Papua itself, in a ceremonial context especially, bisj-poles can reach up to six metres or more. It also lacks the protrusion, or tsjemen, normally found at the top of the carving.

There is more to this story however, than simply another evolution in form. By reappropriating a carving tradition that has been commodified in Indonesia and the west, these carvers and their community have asserted their control over the form, repossessing one of the most symbolically charged pieces of Asmat art. The Melbourne bisj-pole highlights the political significance that the bisj-pole can have, something which is not acknowledged in books about the Asmat, or in exhibitions such as the Rockefeller display in New York. In this way, it challenges the characteristically apolitical way Asmat art is used in festivals, museums and galleries. In doing so, it brings a cultural artefact onto centre stage in a claim for West Papuan independence. ii

Kipley Nink (k.nink@nma.gov.au) is a curator at the National Museum of Australia. She is currently completing an honours thesis on Asmat art at the Australian National University.