Jacqui Baker

Since their separation from the armed forces in 1998, the police have competed

|

When former armed forces commander Wiranto announced in 1999 that the Indonesian National Police were to be pried from the military and made an independent body tasked with security, press response was largely tepid. This was indicative of how little the public, and the military itself, believed that President Habibie’s reforms would actually change the military’s control over internal security.

Long discredited within the military family as a corrupt, bumbling institution of little capacity and vision, the police now handle the biggest internal threats of contemporary Indonesia.

Yet, as Indonesia’s democracy has consolidated over the past 10 years, the Indonesian National Police has been thrust into the forefront of security. Long discredited within the military family as a corrupt, bumbling institution with little capacity and vision, the police now handle the biggest internal threats of contemporary Indonesia – terrorism, communal violence and separatist conflict. For many civil society activists, the rise of the police represents an essential tenet of democracy – civilian supremacy in matters of security and a military firmly lodged in its barracks. To the military, it is a perverse inversion of the old familial relations inside the security apparatus. In ABRI, the militaristic institution that administered the police, army, navy and air force under General Suharto’s 32-year regime known as the New Order, the police were the ‘youngest child’ or ‘anak bungsu’. Now that ‘anak bungsu’ suddenly has the authority to bark out orders.

National tensions

Although initially befuddled by their independent status, police officers have now started to flex their political muscle in front of their ‘older siblings’ in the military. Out of respect for the old ‘ABRI family’, little is said publicly. Instead, the generals have fought out their turf wars over the ‘lahan’ (fertile field) of security through their proxies in civil society, parliament and the civilian bureaucracy. This proxy war has been most evident in recent debates over the national security bill, currently being drafted by the Department of Defence, the bureaucracy that administers the military and that the police see as the military’s main ally.

The police have rejected the new draft bill outright. Their hostility is due to their fear that it will roll back their newfound authority. Legal reforms since the fall of Suharto are widely understood to have put the police at the forefront of domestic security. The general agreement is that the police are responsible for everyday order and security. Even lowly police stations have the power to second the military to police operations.

However, in legislative terms, the sector is still murky. The police bill of 2002 carved the scope of police authority out of the areas formerly under military jurisdiction. However, in 2004, parliament also passed a military bill that continues to provide a legal basis for the military’s involvement in security incidents of a distinctly civilian flavour, such as strikes and threats to the national economy.

The national security bill is supposed to clarify the scope of authority of the military and the police in administering domestic security. However, by refusing to acknowledge the bill, the police are suggesting that they would prefer practices to continue under the current arrangement.

Physical clashes

These national tensions around structural and legislative issues have been accompanied by ongoing clashes in the regions between military and police officers. According to media reports, the clashes typically occur over a day or two, usually beginning with a fist fight between a number of individuals from the military and the police, and expanding out to include a greater number of soldiers and officers using weapons to battle it out. Weak on firepower and tactical skill, police have very rarely ‘won’ one of these battles. Ironically, Jakarta is one of the few provinces not to have hosted a major altercation. The police and the military elites have quickly dismissed the violence as a kind of over-enthusiastic horseplay with guns. Their views are not entirely a white-wash. Macho spats within the great ABRI family over girlfriends or petty slights have apparently occurred since the 1950s.

|

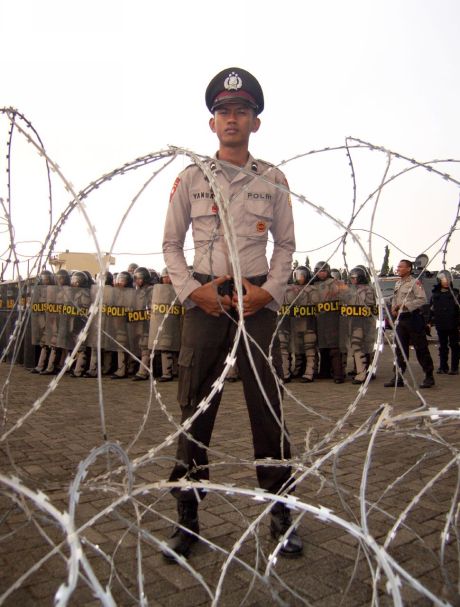

A ‘brimob’ paramilitary police officer takes part in a

|

However, most of the altercations of the past 10 years of Indonesia’s democratisation era have followed patterns entirely different from those of previous wrangles. In all of the post-1998 cases, personnel involved in the spats are not a mixture of the police’s older siblings from the navy, air force and army. Rather, the violence nearly always occurs between members of the two institutions that claim direct authority over territorial security: the police and the army. Moreover, some sections of the police and the army appear more likely to be involved in such fights than others. Attacks are most frequently initiated by members of an army battalion permanently stationed in a region. Their usual targets are either Brimob (Mobile Brigade), the paramilitary police force controlled centrally and seconded to regional police stations or, where the civilian police are involved, personnel stationed at the sub-district commands, the Polres. The sub-district commands have benefited most from recent police reforms by gaining some fiscal and human resource powers from the centre.

Police and army personnel wounded or killed in the clashes are always from the second-lowest and lowest bands of officers, suggesting that it is these foot soldiers that are doing the bulk of the fighting. Though the generals label them ‘loose cannons’, actually the opposite is true. Those on the bottom rungs are the ones who most feel the pinch of limited resources and are dependent on their immediate commanders for career advancement and access to the informal payments that supplement their meagre salaries. They are therefore unlikely to engage in physical violence without the knowledge, or instruction, of their seniors. Unsurprisingly too, police tend to nurse more wounds from the clashes, in terms of both damage to infrastructure and loss of human life. Despite the loss of dozens of lives on both sides, frustratingly little information is available on the results of investigations into the hostilities.

Turf war

Although security apparatus personnel are reluctant to discuss the post-1998 rash of battles between the police and the army, most Indonesian analysts agree that that such clashes generally flow from turf wars for control of locally based semi-legal and illegal economies. They argue that newly emboldened police officers are demanding a larger share of the funds generated by control of the supply or distribution of commodities such as petrol and narcotics, or the provision of security services to illegal industries such as timber smuggling and prostitution.

Many clashes have occurred in Indonesia’s conflict areas of Papua and Poso. Commentators have long argued that conflict conditions provide security forces with a cover for profiteering. But even more clashes have occurred in regions that have few resources of national importance. Sites of conflict such as Bulukumba in South Sulawesi and Binjai in North Sumatra, for example, do not have the economic clout of places like Exxon Mobil’s plant in Lhokseumawe, Aceh, or even the Medan city centre. ‘Vital projects’ such as mines or plantations that lie at the heart of the national economy are the most significant off-budget money spinners for security actors, and therefore according to the conventional wisdom should have the greatest potential for clashes. But the armed spats between the army and the police are not usually around these sites.

Every day, security in this vast archipelago is actually provided by a series of fragile and shifting pacts between locally-based police and military leaders

In fact, the small number of clashes in resource-rich areas is a telling indication of how the military–police relationship works on the ground. So much has been made of the tension between these institutions that the underlying cooperation between them is often forgotten. The great national resources that provide the biggest off-budget funds of the security apparatus are not a source of conflict precisely because the military and the police have established agreements for cooperation and mutual gain around those industries. This cooperation is part of a bigger picture. Police and military personnel routinely coordinate their work even in everyday security operations such as controlling public demonstrations, border control and transport security.

Every day, security in this vast archipelago is provided by a series of fragile and shifting pacts between locally based police and military leaders. Even the most cursory scan of regional newspapers throws up evidence of the ongoing relationship. In 2006 mass demonstrations in Makassar over the alleged rape of a local girl by an ethnic Chinese were pacified by police backed up by a large military contingent. In May this year, in Kampar, Riau, police deployed the military to break a blockade in an illegal logging case. Even roof riders on PT Kereta Api trains in Jakarta were busted in a series of raids last February by a joint military and police taskforce. Despite the grey areas in legislation, these are threats to security that border on the banal and lie firmly under police authority. Why then do the police invite the military back into the management of day-to-day security?

Family is family

The reason the police agree to military units helping to provide internal security is rooted in police officers’ continuing belief in the kinship of ABRI. Under Suharto’s New Order regime, military education engendered familial ties, both real and imagined, between the officer classes. In the Armed Forces Academy (AKABRI) officers across the military and police participated together in generalised military training for one year. As they climbed the career ladder, senior generals often found themselves reunited with their classmates in officer schools or the National Resilience Institute (Lemhanas) for more advanced courses of study, creating tight military–police cliques at the senior level. Evidence of these upper echelon buddy groups can be found in police–military veteran clubs which continue to wield significant political influence, or in businesses run jointly by police and military. Rank-and-file police officers do not get these elite scholarly opportunities. Yet they continue to experience a deep nostalgia when remembering ABRI. Officers in both the army and the police frequently reminisce to me of a time when the security forces were a ‘compact’ family, united in defence of Indonesia.

But as in all good families, the relationship is intimate, complex and ambiguous. Police affection for ABRI is also tinged with unease about the tenure of police authority over internal security. Many police officers in the middle rungs of the hierarchy harbour anxieties that the seesaw of security politics might one day tip back in favour of the army. Asked why the army was permitted to maintain some of its protective rackets under his territorial command, a middle-ranking general said to me, ‘Who knows how long this will all last? And who knows when the military will be back?’ From a police perspective, the army’s return to power not only would propel the police back to ‘youngest child’ status in the great military family, but might also prompt acts of older sibling vengeance for police disloyalty. Indeed, given that Indonesia’s last experiment with messy democracy ended in military rule, it is not so surprising that some officers express deep-rooted anxieties about the longevity of civilian supremacy.

That police are willing to cooperate with the military at the local level in ways that are as yet unregulated and unaccountable is what presents the biggest challenge for ongoing democratic reform of the security sector. If democracies by definition hinge upon a military limited to defence and a civilian force charged with internal security, what might be the consequences for Indonesia’s democratisation if the military is consistently being invited back into the field of policing? Regulation of the police–military relationship is urgent, but is blood thicker than water? ii

Jacqui Baker (j.w.baker@lse.ac.uk) is currently doing PhD research in Indonesia on police reform.