Laurens Bakker

Indrawan Suryadi |

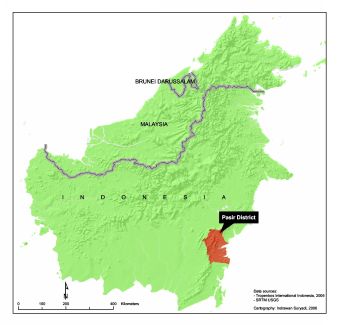

Ever visited an open-pit coal mine just for the pleasure of it? Or a multi-hectare oil palm (kelapa sawit) plantation? You can in Pasir, the southernmost district of East Kalimantan, where the local tourism office offers day trips to these destinations. Unusual tourist drawers these may be, but the Pasir tourism office’s pragmatic approach to make a tourist destination out of the district does not lack in inventiveness.

Conspicuously absent from the Lonely Planet, Pasir has little to recommend it as a tourist destination for foreign travellers. Yet fiscal arrangements of regional autonomy legislation (Law No. 25 of 1999 and Law No. 33 of 2004) allow the regions to apply for central government financial assistance in developing tourism. They also have tourism revenues largely flowing to the district treasury. For these two reasons, the Pasir district government understands that developing a viable tourism industry is well worth its while.

Currently, the district government’s tourism office focuses on cultivating a local market for Pasir tourism. Indeed, much of this market is well-endowed. East Kalimantan’s provincial gross product is only surpassed by Java’s provinces. Being much more sparsely populated but rich in gas, coal and natural resources, East Kalimantan’s economy is much stronger. The province has a sizeable proportion of citizens wealthy enough to spend money on the joys of tourism.

Pasir has few attractions of the type that are traditionally identified as tourist spots. There are two or three waterfalls conveniently located along the main highway, where a cluster of stalls sell noodles and sweets, and where motorists traveling between Banjarmasin and Balikpapan may stop to have their picture taken. There is also the palace of the former sultan, restored in the late twentieth century. Unfortunately it is hours removed from the main motorway and only attracts visiting crowds during the weeks before and after Idul Fitri, when the palace and nearby sultan’s mosque are side destinations for those visiting the burial ground of the royal family. A number of graves are considered to be holy places and people come from as far away as Samarinda and Banjarmasin to visit them.

Deer sate

|

Sate payauLaurens Bakker |

Pasir does have one attraction that has travellers making detours and brings in whole Balikpapan families for one-day visits, but official promotion sits uneasily with other government policies. Small food stalls in the capital city of Tanah Grogot sell sate payau, sate made using sambar deer (Cervus unicolor) meat. Sambar deer live in Pasir’s mountain forests, but had become so rare in the early nineties that the government established a breeding farm to supplement the wild deer population and prevent extinction. As this population increased hunters have been able to ensure a steady supply of meat to the food vendors. As a result, sate payau has gained fame as Pasir’s culinary benchmark. Sate payau is not officially promoted, since doing so would contravene the endangered status of the animals. But the dish is a highlight at government banquets.

Coal mines and oil palms

Pasir’s main source of revenue is PT Kideco Jaya Agung, a majority Korean-owned mining company operating a number of large, open-pit coal mines. What the district has most, however, are extensive oil palm plantations. Nearly 60,000 hectares or 65 per cent of Pasir’s agricultural area consists of small local oil palm gardens and large private and state plantations. The produce of all is bought and processed by PT Perkebunan Nusantara XIII, a large state-owned plantation company owning all three local oil palm processing plants. Well-embedded in the district’s infrastructural network, mines and plantations offer accessible locations to those looking for an experience more in line with Pasir’s defining features. According to Bapak Muaz, a bureaucrat from the tourism office, the plantations offer city people the possibility of visiting a natural environment without the difficulty of travelling to remote forests. ‘The air is clean and people can see flowers and birds’, he told me, ‘one company has agreed to build some guest lodges at the plantation’s highest point, so guests can wake up to a wonderful sunrise vista.’

|

Oil palm plantationJan van der Ploeg |

Although he applauds the tourism office’s inventiveness and enthusiasm, Pak Suprandi, a middle cadre official in another branch of Pasir’s government apparatus, expects little of their endeavours. ‘Pasir is industry and farmers’, he told me. ‘People with a bit of money to spend do not want to look at those. My family and I travel to Balikpapan for the weekend, and go for a holiday to Jakarta or Makassar once or twice a year. That is expensive, but it is fun. A palm oil plantation is not fun.’ Pak Suprandi may be right. Pasir’s well-to-do do not stop at weekend visits to Balikpapan’s hotels. Its airport has daily flights to Jakarta, Bali, Makassar, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur. Pak Suprandi has visited Kuala Lumpur and Singapore together with colleagues, and has taken his family to Bali. Many of his colleagues have been to Bali as well.

‘Bali is unusual and pleasant’, Pak Catu, another local government employee points out. ‘We joined an all-Indonesian package tour from Balikpapan, enjoyed the hotel and swimming pool, took a cruise, had a banana-ride and ate at an all-you-can-eat fish barbeque. We stayed in a hotel without foreign tourists but enjoyed watching them on the street.’ Pak Catu also feels that other parts of Indonesia offer more interesting sights than Pasir. In addition, he points out, budget flights connect Balikpapan to Kuala Lumpur and from there to various other countries allowing tourists from East Kalimantan to travel cheaply throughout Southeast Asia.

Local plantation and mining companies enthusiastically agreed to cooperate in the tourism development, especially when tourism office staff pointed out that their work is novel and intriguing for city people. But visitors are still limited in number. Pasir’s own urban middle class prefers to travel to the big cities of Balikpapan or Samarinda for shopping, dining and parading rather than spend the weekend among the oil palms. Visitors from the cities occasionally do stop among the plantations for a break and some pictures, but very few feel the urge to book a tour.

Cultivating the lower end

Pasir’s tourism office is aware that wealthy locals are less than enthusiastic about visiting local tourist sites. But they argue that Pasir’s destinations could easily be visited by those with less money as well. The office has begin cultivating a local working class market by organising a pop dangdut festival, a beach barbeque and various performances of local traditional dances. These were modest enough projects, but were quite successful ones, drawing crowds from Tanah Grogot’s wide surroundings.

Pasir’s own urban middle class prefers to travel to the big cities of Balikpapan or Samarinda for shopping, dining and parading rather than spend the weekend among the oil palms.

Pasir is no Bali, and cannot compete with Singapore for tourist favours. Yet tourism staff have recently come up with the new idea of developing a hotel or even a resort along one of Pasir’s more remote beaches, thus aiming for a secluded upmarket spot to draw the nation’s, and perhaps Singapore’s and Malaysia’s, wealthy middle classes. Although nothing more than plans at present, such a project would tie in with the rosy economic future the district government envisions for the area. Pasir is to go forward in the Southeast Asian region and attract international investors and visitors to boost its economy. The development of an airstrip is currently under discussion. It would bring Tanah Grogot within minutes of Balikpapan’s airport. As soon as scheduled flights commence, visiting the district will be easy and convenient. The oil palm might not live to see this. Their growth makes such demands on the soil that the district government has issued a ban on new plantations and is considering shifting to rubber plantations instead. The tourist office sees no problems. Rubber plantations are every bit as touristy as oil palms. ii

Laurens Bakker (L.Bakker@jur.ru.nl) is completing his PhD dissertation on the dynamics of land tenure in East Kalimantan at the Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.