Andrea Acri

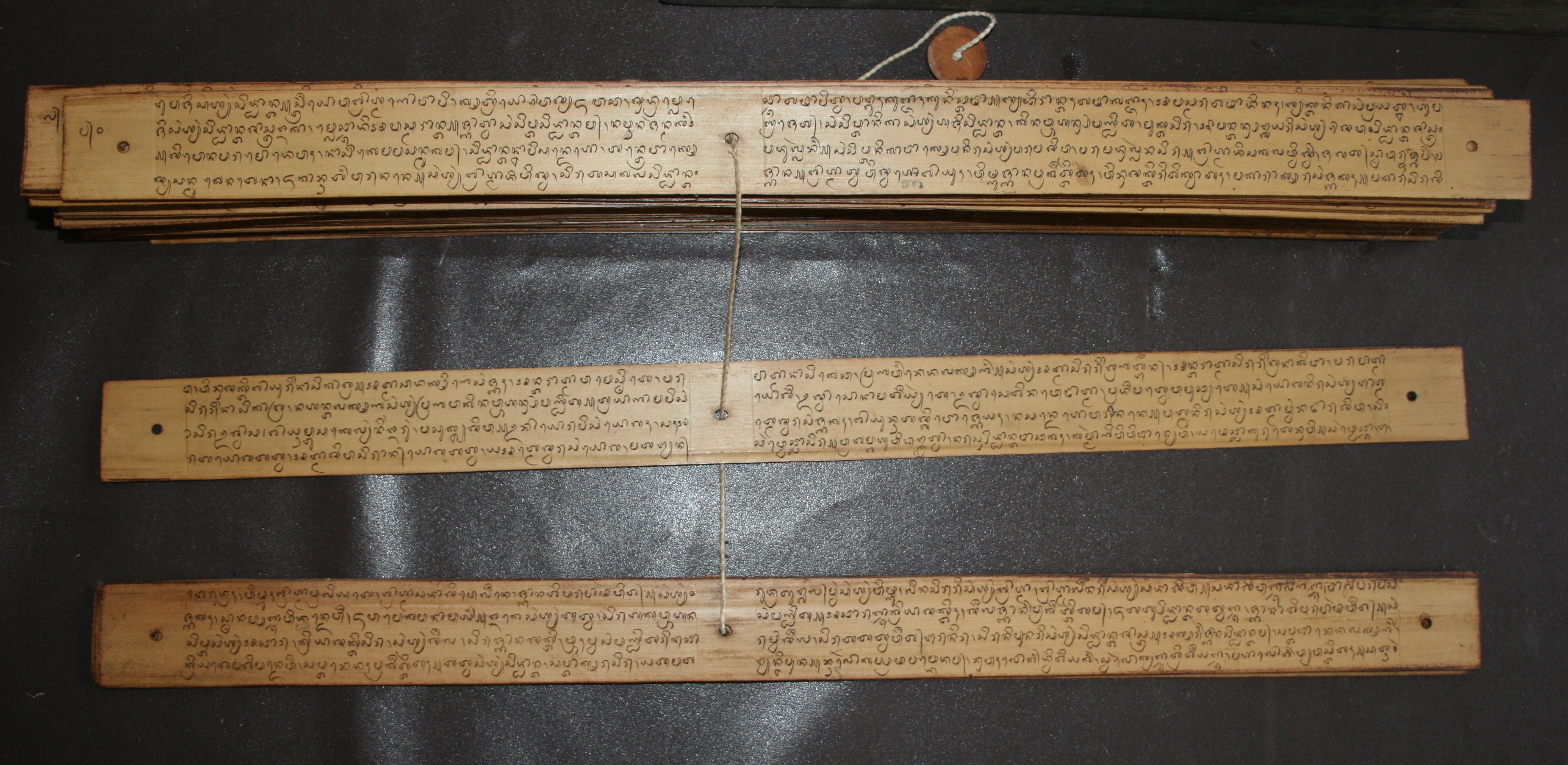

Palm-leaf manuscripts (popularly known as lontar) are among the most iconic and unique manifestations of tangible and intangible cultural heritage preserved on Bali from the past through to the present day. The literature and religious lore of Balinese and ancient Javanese traditions have been reproduced through the centuries via a learned tradition of writing and reading texts on lontar. The refined technique of engraving words in the beautiful Balinese script on processed palm-leaves originates from pre-modern India. In India, this pre-industrial technology has mostly fallen into oblivion, but on Bali it is still used alongside digital print technology.

Traditionally, lontar have been handled by the Brahmanical or aristocratic elites, religious and ritual specialists, folk healers known as balian, and even cultured commoners. The largest collections of such manuscripts have been found in Brahmanical compounds and royal palaces, but many common households, especially in the northern and eastern provinces, often hold a few lontar. According to one estimate, there may be tens of thousands of them in Bali alone.

If properly stored and cared for, lontar can last for hundreds of years. (Andrea Acri)

If properly stored and cared for, lontar can last for hundreds of years. (Andrea Acri)

If properly stored and cared for, lontar can last for hundreds of years, far longer than modern paper books. If neglected, they easily crumble under the attack of insects, fungi, and a humid tropical climate. While many of the lontar kept in private households lie in a dilapidated state, most are kept (and worshipped) as sacred heirlooms inherited from the ancestors, or regularly used (that is, read, and/or copied) as ‘books’ by the people in the business – that is, by the very few Balinese who can read high Balinese, Old Javanese (Kawi), and Sanskrit. Apart from language capability, the reader must also be able to understand the Indic-derived Balinese script.

The body of texts preserved on lontar encompasses various genres: works of literature; historical chronicles; treatises on medicine, architecture and theatre; scriptures on matters of Hinduism and Buddhism; and manuals on ritual, meditation, and magic.

Documentation and access

In their attempt to collect and preserve lontar, and to make the texts written on them accessible to scholars and the Balinese community at large, Dutch colonial authorities (in collaboration with local intellectuals) established the Gedong Kirtya library in Singaraja in the late 1920s. In 1939, the Dutch philologist Christiaan Hooykaas and the Balinese man of letters I Gusti Ngurah Ketut Sangka started a project involving the systematic typing of these texts onto paper in romanised transcription. After a halt due to the Japanese invasion during WWII and other vicissitudes, the so-called ‘Proyek Tik’ (Typing Project) was resumed by those two scholars in 1972, and continued, under the leadership of Hedi Hinzler and I Dewa Gede Catra, from the 1980s until the first decade of the twenty-first century.

While many of the lontar kept in private households lie in a dilapidated state, most are kept (and worshipped) as sacred heirlooms inherited from the ancestors. (Andrea Acri)

While many of the lontar kept in private households lie in a dilapidated state, most are kept (and worshipped) as sacred heirlooms inherited from the ancestors. (Andrea Acri)

The many thousands of typewritten copies of texts resulting from this relentless work can now be accessed in Bali, in the Leiden University library in the Netherlands, and in a few other institutions in Australia, Europe and the US. Since Indonesian independence, several public repositories of lontar and/or romanised copies have been established in Denpasar under the patronage of local government or institutions of higher learning. Substantial collections of lontar are held in the libraries of Udayana University, the Dwijendra Foundation, in the Pusat Dokumentasi Budaya Bali (Centre for Documentation of Balinese Culture), in the Bali Museum, and in the Balai Bahasa (Centre for Language).

In spite of these admirable efforts in preservation, conservation and popularisation of lontar, knowledge of the languages (and even the script) of the body of texts the Balinese have inherited from the past remained the preserve of a restricted pool of people. The endeavour to make traditional literature, and especially religious texts, accessible to the masses goes back to the 1930–40s. By that time, stencilled pamphlets, printed books, periodicals, and textbooks started to circulate among commoners, who were by then becoming literate, as well as among the educated elites.

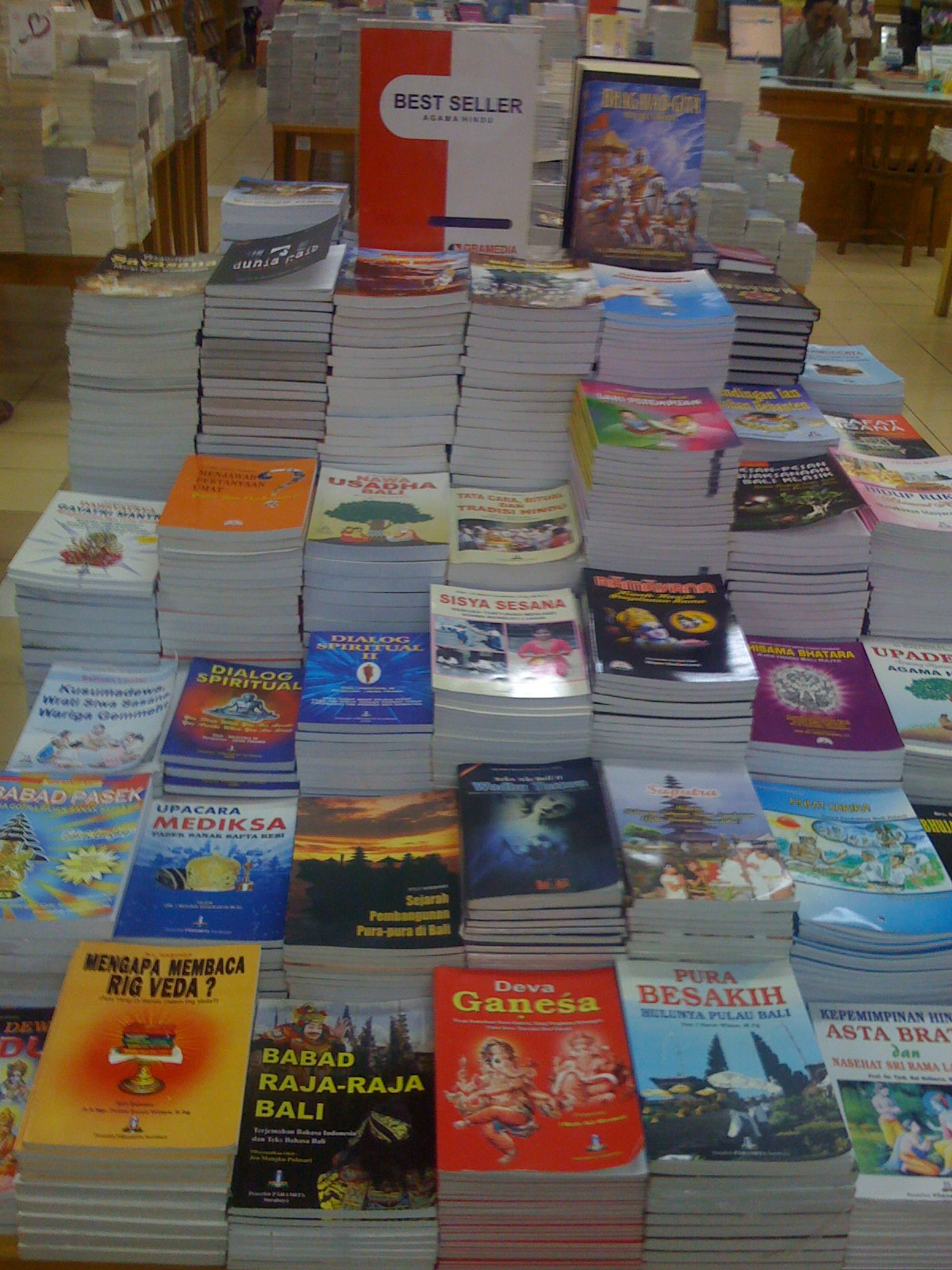

In the last two decades, Balinese bookshops have been flooded with books on Hinduism. (Andrea Acri)

In the last two decades, Balinese bookshops have been flooded with books on Hinduism. (Andrea Acri)

Those cheap publications, usually written in modern Malay/Indonesian or Balinese, were primarily aimed at edifying the majority of Balinese in matters of Hindu doctrine, ritual, and morality. This trend has endured to the present day: especially in the last two decades, Balinese bookshops have been flooded with books on Hinduism. These publications include Indonesian translations of Sanskrit ‘canonical’ Hindu scriptures such as the Bhagavad Gita, the Vedas and the Puranas; editions and translations of ancient Old Javanese scriptures; and booklets on ritual matters, meditation, magic, as well as wider socio-religious issues relevant to the Balinese community.

Ongoing relevance

Interestingly, these popular and accessible publications have not entirely replaced lontar, which perhaps have remained the media par excellence for the preservation of religious lore. The movement of the texts is not only from lontar into writing: it is not uncommon for printed books, pamphlets or typewritten romanisations to be turned into lontar. A recent example is a copy of the Old Javanese Hindu text Dharma Pātañjala. Having survived in a single (circa fifteenth-century) palm-leaf manuscript of West Javanese provenance, this pre-Islamic text was unknown on Bali. Working with a PC-typed romanised edition, Ida Dewa Gede Catra transcribed it into Balinese script on a lontar in 2007. Because of its importance for the Balinese Hindu religion, this lontar is now part of the Gedong Kirtya collection.

Lontar leaves undergoing desiccation. (Andrea Acri)

Lontar leaves undergoing desiccation. (Andrea Acri)

Nowadays, the activity of writing on lontar is still carried out, on a limited scale, for personal or communal edification (through ‘reading clubs’), as a form of art, in cultural contests, for religious or ritual purposes, as a pious duty to one’s own ancestors, and – perhaps most importantly – to ensure the ‘survival’ of Balinese culture, which locals perceive to be under threat from westernisation and modernisation. To overcome this predicament, in recent years government authorities, intellectuals and religious leaders have promoted the revival of traditional forms of artistic, cultural and literary activity, including lontar writing. Many of the texts that were traditionally handed down on lontar and circulated within a restricted circle of literati are now read, sung, or discussed in public contests (such as the Utsawa Dharma Gita, ‘Festival of Sacred Songs’), on TV and in radio broadcasts (such as Kidung Interaktif, ‘Interactive Kidung’), and on the internet.

Elites and knowledge

The advent of digital technology has triggered an efflorescence of blogs and websites by private individuals and organisations, where the texts are reproduced digitally in roman script. A set of unicode-compliant fonts has been developed, as well as keyboard layouts, to facilitate the typing of Balinese script on personal computers. Most of the items in the lontar collection of the Centre for Documentation of Balinese Culture in Denpasar have been digitally photographed and uploaded in the form of the ‘Balinese Digital Library’ on the popular website archive.org. Thanks to this project, high-quality images of nearly 3000 lontar can now be freely accessed and downloaded from the internet.

Raw leaves being prepared in Amlapura. (Andrea Acri)

Raw leaves being prepared in Amlapura. (Andrea Acri)

One may see these recent developments as a direct continuation of the anti-reactionary agenda of westernised Balinese urban intellectuals who, since the 1930s, struggled against the Brahmanical elites to ‘desacralise’ and ‘democratise’ the production and sharing of knowledge on Bali – activities involving lontar that were traditionally carried out by high-status people. Like those early intellectuals, their contemporary heirs see lontar not just as powerful magical objects but as media for the storage of texts which can later be reproduced and read in different formats and on different platforms ¬– for example, in roman script on books, or as text and image files that can be accessed on computers, tablets, and smartphones.

Further, they believe that the esoteric teachings that have been the preserve of religious authorities and ritual specialists (such as the priests known as pedanda and pemangku) constitute a body of knowledge that is relevant to the religious and moral edification of modern man. As such, it is a matter of some urgency that they be freely shared among the members of the community and the world at large, especially at a time when the Balinese are striving to preserve their minoritarian religious and cultural identities in rapidly-developing and predominantly Islamic Indonesia.

Will recent paradigm shifts in the Balinese cultural and media scenes supplant lontar as a medium to share and produce knowledge? It is more likely that the world of lontar will continue to exist side by side with the new technologies of our digital age. Teams of engineers are currently working on perfecting the technique of writing on lontar leaves with a laser pen instead of engraving them with a metallic stylus, which could dramatically speed up the writing process. This initiative, along with the renewed interest in traditional lore that has developed among the younger generations in recent years, will ensure that lontar continue to play an important part in the dynamic dance between ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’ that has made Balinese culture so unique. Hopefully, the artifacts themselves will not outlast the traditional know-how about the languages, texts, and ideas transmitted on them, and lontar will not become mute witnesses to the rich Javano-Balinese cultural past.

Andrea Acri (a.acri81@gmail.com) is visiting research fellow at the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (Singapore).