As a number of communities in East Nusa Tenggara reject mining, tourism as a resistance strategy can be equally exploitative

Mining or tourism?

In December 2008, West Manggarai’s then-district head, Fidelis Peranda, granted a concession to explore for gold on the Batu Gosok peninsula north of Labuan Bajo to a Chinese mining company, PT Grand Nusantara. This immediately caused a stir since several hotels were located not far from the exploration site, and it appeared that the tailings, if the company were to ultimately open a gold mining operation, would drain directly into the North Flores Sea. At the time, the Komodo National Park, both a land- and marine-based national park just west of the island of Flores, was drawing increased national and international attention. It was under consideration for one of the ‘New 7 Wonders’ of the natural world, a global contest supported by a Swiss organisation.

View from the mine site at Batu Gosok, West Flores. Any waste from the proposed 2008 site would have drained into the North Flores Sea. (Florianus Surion Adu)

More hotels and other tourism developments were being built in and around Labuan Bajo and increasingly north, towards the Batu Gosok peninsula. Those working in tourism and those involved in various conservation activities associated with the park were horrified at the idea of a gold mining operation that could poison the seas of Flores. As the operations began, indeed visitors to the nearby hotels began to be disturbed by the activities, and outrage increased. Demonstrations were held multiple times, and many residents of West Manggarai District increasingly put pressure on the local government to halt the mining activities.

This was not the only district in East Nusa Tenggara province where mining became controversial. Across the province, ever since the dramatic 2007 attempt to open a gold mine in Lembata with plans to evacuate up to half of the island’s population, resistance to the mounting number of licences allocated by district heads was growing, with the Catholic church in the lead. West Manggarai was different, however. East Nusa Tenggara is predominantly Christian, but Muslims make up a significant number of West Manggaraian residents. These residents mobilised against mining, not so much at the behest of the church, but because of the perceived dissonance of mining with tourism developments.

So adamant were the residents that mining had no place in the district that Fidelis Peranda was voted out of office in the 2010 pilkada (local direct elections), and his deputy, who promised an immediate moratorium on mining, was voted in. True to his word, the new district head Agustinus Ch, Dulla closed all the mining operations where exploration was in progress, causing PT Grand Nusantara to sue the local government: a case of breach of contract that the company won. Dulla, however, would not let them return, and West Manggarai, unlike other districts in East Nusa Tenggara with active mining licences, has been free from mining activities since then. To the great joy and pride of West Manggarai residents, especially those living in the town of Labuan Bajo, the Komodo National Park won the New 7 Wonders status on 11 November, 2011.

Locals protest mining in front of the district head's office in 2009. Fidelis Peranda was voted out the following year. (Florianus Surion Adu)

What are extractive industries?

Back in 2008, the governor of NTT had given a mining licence to the company PT Fathi Resources, a subsidiary of Australian company Broken Hill Resources, to explore for gold in the two neighbouring districts of Central Sumba and East Sumba. According to the mining law of the time, if a concession crossed over district boundaries, it was the governor, not the district head, who had the right to give out the mining licence. The concession given in Sumba was very close to the boundaries of sections of another national park in East Nusa Tenggara: Lai Wangi Wanggemeti and Manupeu Tana Daru, located in East and Central Sumba respectively.

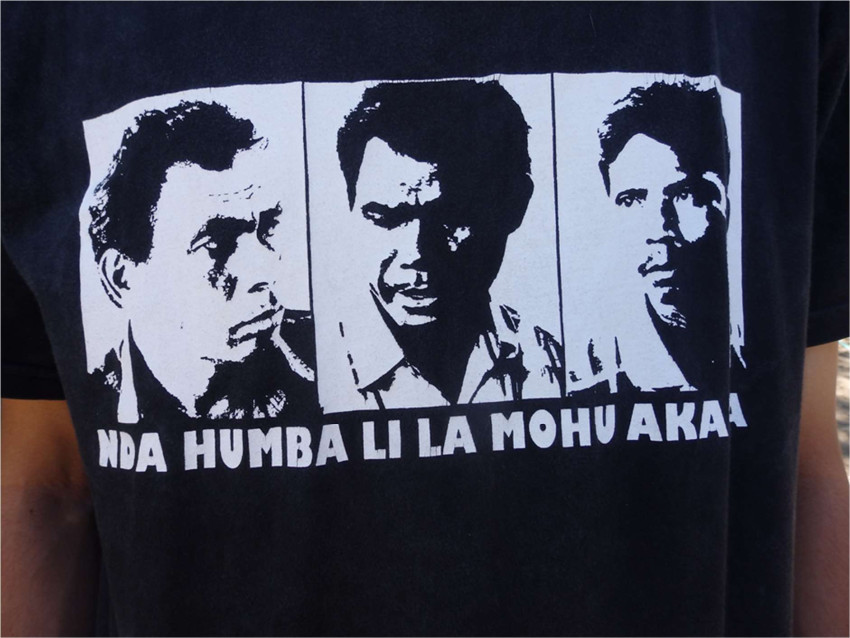

After a few years of gold exploration activity, villagers in the village of Pakaroku, Central Sumba, began to complain about their rice crops dying and livestock sickening due to the operations. Additionally, there were complaints of human illness. The government, however, took no action, so the villagers themselves began to demonstrate against the company, eventually burning and destroying some of their equipment. Three men, two brothers and their cousin, were charged as vandals and sentenced to 10 months in jail in 2011.

The brothers and their cousin were hailed as heroes upon their release. (Maribeth Erb)

When they were released from jail, environmental activists held the first Wae Humba Festival in 2012 to commemorate their heroic status and to unite the four districts of Sumba against mining. ‘Wae’ means water in the Sumbanese languages, and in a dry island such as Sumba, preservation of water sources is extremely critical. Mining activities were taking place precisely in the mountainous areas where water sources were located. Over the past five years, the communities of Sumba have travelled for the Wae Humba festivals to different main water sources in the mountains of Sumba. There they have offered ritual sacrifices to respect these springs and rivers, and ask their ancestors for protection in their efforts against mining on Sumba.

Meanwhile on Flores, after the Komodo National Park won its New 7 Wonders title in 2011, wealthy investors who recognised the tourism potential of East Nusa Tenggara – particularly those from Jakarta and Bali – began to buy up land along the Florenese coast. National level events proliferated to accelerate tourism promotion; for example, the Sail Komodo yacht race of 2014, and in 2016 Labuan Bajo, as the gateway to the Komodo National Park, was named by the central government as one of the 10 national tourism priorities. This has meant central government projects for infrastructure, such as the new marina slated to be finished by the end of 2017, have poured into this small town.

Land has continued to be bought at a rapid rate and land prices have risen to unprecedented levels, well beyond the ability of locals to purchase land in the area. People say that the land along the whole coast of Flores has all been bought up by outsiders, and many new developments continue to spring up to cater to the tourism potential of Flores. Big conglomerates from Jakarta and many foreigners now appear to control most of the tourism businesses in the small town and surrounding islands of the park. Have the locals lost control of tourism developments as, indeed, seems to have happened in Bali so many years ago?

Indeed, on the neighbouring island of Sumba, many local communities have come to identify tourism as one of the ‘extractive industries’ that threaten their culture and livelihoods. Similarly to Flores, the coastal land is rapidly being purchased by big conglomerates and foreign investors. Also on Sumba, corporations are buying or leasing large parcels of land for plantations, such as clove and jophara (used for biofuel), and some social and environmental activists feel that these developments are increasingly marginalising and displacing local communities. These issues were raised at the fifth annual Wae Humba Festival in October 2016, where other water- and land-hungry ‘extractive industries’ such as plantations and large-scale tourism were equally rejected, in efforts to promote community empowerment and environmental conservation.

The communities of Sumba offer ritual sacrifices to show respect for water sources and to ask for protection. (Maribeth Erb)

Future challenges

The new Local Governance Law 23/2014 took away the right to grant mining concessions from district heads. The law, however, was received with mixed feelings by communities, companies and activists. Although it was clear that the district heads were abusing their power under the earlier decentralisation laws, often funding their election campaigns with money from mining companies looking for concessions, the new law was not a guarantee against corruption. Activists in East Nusa Tenggara and even some of the province’s operational mining companies worry that local activities, needs, and opinions will be ignored as the right to allocate licences is transferred to the distant capital of Kupang. East Nusa Tenggara is an archipelagic province, with expensive and difficult transportation between islands. Will the local communities be at all included in the discussions before a mining licence is granted by the governor?

It seems that a partial answer is to be found from this year’s developments. With apparent disregard for the earlier events that led to the rejection of mining, the governor issued a gold mining operation licence to PT Grand Nusantara, which had previously been chased out of West Manggarai in 2010 by the district head. With this license, the level of operation was raised from ‘exploration’ to ‘exploitation’, thus approving the operation of a gold mine in the tourism-focused part of Flores. The mining law regulations, however, do insist that an environmental impact study (AMDAL) is required, and one of its provisions is that the community must be ‘consulted’ (‘sosialisasi’), though the rights of rejection under these provisions are unclear.

Signs plastered at the entrance of the mining company property show local rejection of mining in 2009. (Florianus Surion Adu)

In March, the community of Labuan Bajo made their thoughts about these developments clear. A meeting to ‘socialise’ the residents of Labuan Bajo about the plans for the mining operation was called by the head of the mining office at the behest of Grand Nusantara. Most of those who were invited, as well as a number of other environmental activists who were not, and who gatecrashed the meeting, stated definitively, ‘Labuan Bajo is not appropriate as a mine site.’ In response, the company representative viewed the meeting as an incomplete consultation exercise, stating that the company ‘will look for a different time to continue the socialisation’ so the requirements for the AMDAL will be fulfilled. This leaves the future of the Komodo National Park, as well as NTT’s other national parks, in doubt. This is true both in terms of the amount of input allowed of the communities living on the boundaries of a potential mine site, but also more broadly in terms of the amount of benefit that they will eventually receive from the various extractive industries in their midst.

Maribeth Erb (socmerb@nus.edu.sg) is an associate professor of Anthropology in the Department of Sociology in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the National University of Singapore.