Online corruption talk in Banten can be vitriolic

|

|

Welcome to Corruption Tourism. (Fesbuk Banten News screenshot) |

The banner with the satirical words ‘Welcome to Corruption Tourism’ appeared on a footbridge at the entrance to Serang, the capital of Banten Province. It was visible to anyone entering the city and read by 52,012 people belonging to the citizen journalism Facebook page Fesbuk Banten News (FBN). The banner played on a theme familiar to many since Governor Ratu Atut Chosiyah was indicted for corruption in December 2013; a theme where Banten is a byword for corruption. Ratu Atut was sentenced to four years’ jail for bribing the Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court, who in exchange was supposed to favour her supported candidate in a disputed district head election in Lebak. She belongs to a dynasty that has dominated the province’s political life since it was established as separate from West Java in 2000. A string of corruption allegations against the family has seen many of them land in jail.

This particular scandal ignited fierce debate on social media about other corruption cases orchestrated by the family since 2000. FBN is one of the most active venues for such debate. Founded in 2010, the Facebook group now has 105,000 members. It is widely seen as the leading online space for investigating, writing and posting news on corruption cases in Banten, particularly on Ratu Atut’s dynasty.

Digital acts of witnessing

FBN adopts a citizen journalism approach: it invites the citizens of Banten to play an active role in collecting, reporting, and disseminating news relevant to the province. In practice it focuses on corruption and dynastic politics. Postings fall into three categories: poor infrastructure caused by corruption, allegations surrounding the family, and corrupt election campaigns. FBN citizen journalists, called ‘dulur’, meaning friend or comrade, post pictures and texts that bear witness to perceived injustices.

Items on poor infrastructure, even without direct reference to corruption, provide an outlet to talk about corrupt dealings. Stories about poor roads are quick to come up in everyday conversation. When I first arrived in Serang, the motorbike taxi driver who took me to explore the city asked what I was doing in town. ‘I am researching corruption,’ I replied, just to give a simple answer.

The driver immediately responded, ‘Corruption? Oh, about Atut’s dynasty. Corruption is everywhere. Look at the roads in Serang, and Banten in general. Very bad, very very bad. Even in the capital Serang the roads are bad.

‘You know what? Our city mayor TB Chaerul Jaman (stepbrother to Ratu Atut) loves off-roading. It is his hobby. So he keeps the road as bad as an off-road track, with holes full of water, mud, gravel, rocks, and stones.’ The driver laughed at his joke.

Different people around Banten would tell me similar stories wherever I went. They always pointed to the poor infrastructure, particularly roads, and how this was related to the corruption of Ratu Atut’s dynasty.

|

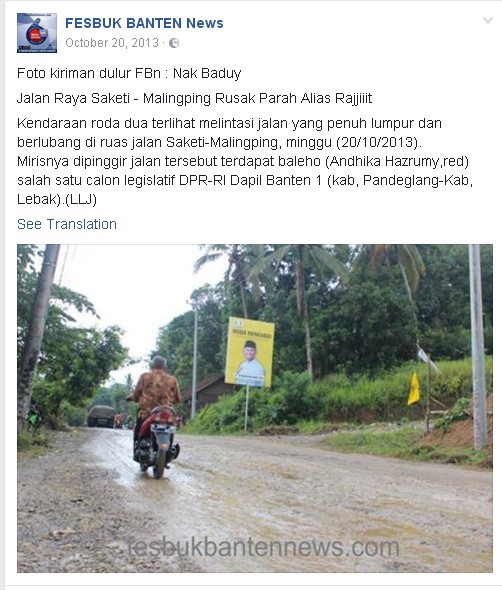

Photo by FBN comrade, Nak Baduy (nickname).

Main road of Saketi–Malingping badly damaged, alias Rajiittt.

A two-wheeler is seen riding along a road full of mud and potholes between Saketi–Malingping on Sunday (20/10/2013). Ironically, on the side of the road there is a billboard (for Andhika Hazrumy [Ratu Atut’s son]) for a national legislative election candidate from Banten Area 1 (Pandeglang and Lebak Regency). (LLJ)

|

Photo by Mang Ripin

A garbage truck passes along the main street of Serang City. Sunday (4/11/2013) (LLJ)

Also depicted is a big puddle on the street, suggesting surface damage. Reflected in the puddle is a billboard with Ratu Atut’s photo.

One anti-corruption activist in Banten told me that ordinary citizens feel corruption is a complex issue. But poor infrastructure, especially roads, is something they find easy to comprehend, as this is a ‘concrete’ way to witness the presence of corruption and really feel it. However, more complex allegations also appear on FBN. One example is the so-called ‘social assistance grant corruption case’, or Kasus Dana Hibah, which absorbed the public’s attention from 2011 to 2014. The suspicion was that large amounts of money from this fund, which was supposed to help the poor in Banten, had been redirected to pay for Ratu Atut’s gubernatorial election campaign in 2011. One of the most detailed FBN reports on this case was written by Uday Suhada, a well-known Banten anti-corruption activist belonging to Aliansi Independen Peduli Publik, or the Independent Alliance for Public Care (ALIPP).

|

Allegation of corruption in discretionary social assistance grant in Banten Province (By: Uday Suhada)

FESBUK BANTEN News - In order not to be accused of slander, herewith I retype a policy made by Banten Governor Ratu Atut Chosiyah that spends the people’s money in the guise of the discretionary social assistance grant in the 2011 fiscal year that smells of collusion, corruption, and nepotism.

I do this because the Banten provincial government has been covering up this policy, which ignores the principle of fit and proper. They do not just keep beneficiaries’ addresses secret, but even hide the decision letter signed by Ratu Atut Chosiyah as if it was a sacred family heirloom. The public, however, has an absolute right to know about it, since the money comes from the people through the regional development budget (APBD).

This posting was one of the longest in FBN and had two parts. One revealed the list of 160 organisations and institutions that had received social assistance, stating the amount for each. Uday Suhada found it suspicious that the dana hibah grants increased dramatically in size immediately before the election. It looked like these organisations and its members were supposed to support her re-election campaign. Some were state-related institutions like the electoral commission (KPU, Panwaslu), the military wives’ association Persit Kartika Chandra, the women’s association Dharma Wanita, the youth organisation KNPI, and the Indonesian Red Cross, PMI. Others were religious organisations like Nahdatul Ulama and local Quran study groups. Some organisations, such as the village cooperative unit Mina Bhakti and the Banten Al-Muslimun Foundation, were fictitious. Money given to them evidently flowed back to the Ratu Atut Team. Leaders of other organisational recipients were also thought to have given some of the money back. Ten organisations were actually led by members of her dynasty. Her sister led PMI, her son led the Banten branch of state youth organisation Karang Taruna, and her daughter led the educational organisation HIMPAUDI. The Banten head of Nahdatul Ulama is now in jail for extensive involvement in the dana hibah scandal.

This scandal was an example of a citizen journalist disseminating news about corruption. Indeed, Uday Suhada explicitly stated that he was motivated by the right of the public to know. As he put it,‘The public, however, has an absolute right to know about it.’ Here Uday Suhada was acting as a digital citizen, making a rights-based claim by witnessing an injustice and reporting it to the public.

Flaming

FBN does not merely enable citizens to perform digital acts of witnessing. It also facilitates readers’ participation in citizen journalism. Audiences are no longer passive recipients of information. They make comments, they ‘like,’ they share. Most of the comments they post about corruption and the dynasty can be categorised as flaming. Flaming is a term for an online behaviour in which participants display hostility by insulting, swearing at, or otherwise using offensive language, in this particular case about Ratu Atut and her dynasty. The posting about poor infrastructure above, for example, attracted the following comments:

‘All of the dynasty members are a disgrace... shameful! May God wake them up! And lock them in jail! Or just hang them... They deserve it, they have abandoned the poor...’

‘Does she pretend to be innocent? As a governor she doesn’t care, she is just busy with her own face, pampering it in the beauty salon, but she doesn’t give a damn about the development of Banten.’

The FBN postings about the dana hibah corruption case also attracted some flaming:

‘She swore in the name of Allah... Very stupid... It was a result of her own greed... She says she is a Muslim but she sucks the blood of the people... She is a devil.’

‘Bang bang tut...akar gulang galing..siapa yg kentut, ANAKnya RAJA MALING...’ [These are the lyrics of a traditional rhyming song, rewritten to read, ‘Who dropped a fart? DAUGHTER OF THE KING OF BURGLARS.’]

These acts of flaming on FBN hardly contribute to polite public discourse. But they do give these citizens a chance to be heard above the otherwise rather polite conversation about corruption heard every day on the streets. Using harsh and vitriolic words is one way in which the citizens of Banten construct a moral public sphere. Their public sphere is an affective, emotional sphere. Here they bring to bear their own sense of morality on their perception of the public good, a morality under threat from corruption. Ordinary citizens are here reclaiming their own collective morality by defacing the immorality of their leaders. They are defacing the dynasty.

M Zamzam Fauzanafi (fauzannafi@yahoo.com) is a PhD student in anthropology at the University of Amsterdam. He is attached to Gadjah Mada University as a lecturer in anthropology.