Ariel Heryanto

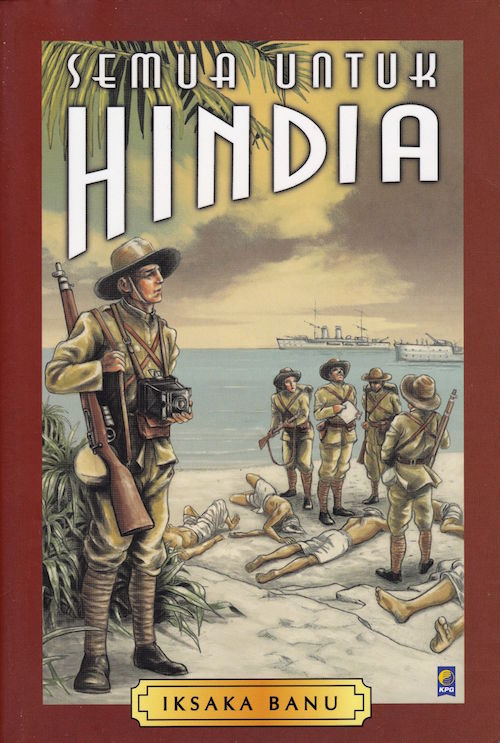

Since the release in the 1980s of Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s internationally acclaimed tetralogy, Iksaka Banu’s Semua Untuk Hindia (2014) has been Indonesia’s first and perhaps sole literary work that radically turns the national history upside down or inside out.

As a piece of literary fiction, the anthology of short stories has earned the recognition it deserves. The Khatulistiwa Literary Award, Indonesia’s most prestigious literary body, selected it as the best prose fiction of the year. However, the book strikes me most profoundly for its achievements in three non-literary areas: a radically new perspective of history; a counter-narrative to the widely held view of Dutch colonialism; and a subversive critique of Indonesia’s hyper-nationalism.

Ironically, the appreciative public has overlooked these elements within the anthology, which I see as perhaps its greatest contribution. To recognise them requires a leap of imagination. Examining the reasons why these non-literary achievements have so far gone unnoticed can provide insight into the dominant consciousness in contemporary Indonesia.

The politics of history

In late 2015 Indonesia made headlines across the international mediascape. Commemorations took place inside and outside the country for the 50th anniversary of the 1965 state-sponsored killings of the suspected leftists. The Indonesian government continued to deny any responsibility, and a number of militia groups threatened to attack commemorative events and publications in Indonesia. A bigger problem is not the failure of many Indonesians to acknowledge or remember the serious crimes of 1965, but rather, that they are poorly equipped to deal with the intricacies of history more broadly.

Historians and historiography occupy a near-pariah status in Indonesia. This is not to say that Indonesia is strongly future-oriented and eschews the past. Critical, secular, and impartial analysis of the past is unknown and at times liable to prosecution. This applies not only to issues pertaining to the recent past, for example, the 1965 killings, but also to Indonesia’s colonial past from which the nation emerged and continues to foreshadow its current existence.

Under the nationalist orthodoxy, all major public discourse is expected to serve nothing but the ‘national interest’. What precisely this interest is, depends on who is in power. The only legitimate history is one that functions as an instrument for promoting the nation’s dignity. It is a history that glorifies Indonesian freedom fighters as super humans who altruistically engaged in diplomatic and armed battles against foreign forces, particularly the Dutch before 1949, and other foreign forces thereafter. With no space for complexity, ambiguity and contradictions, it is difficult to differentiate between history and myth or caricature. Most public discussion of history is framed within the binary opposites: the noble national ‘self’ versus ‘foreign’ evils; friends versus foes; heroes versus villains; or right versus wrong.

Writing and reproducing history is so highly political, that it becomes almost sanctified. Ironically, as the official history is made sacred, history has become one of the most boring subjects for teachers and their students alike. Departments of history in universities are extremely poorly resourced.

A product of 20 years of research, Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s Bumi Manusia (1980), Anak Semua Bangsa (1980), Jejak Langkah (1985), and Rumah Kaca (1988), offered the first major blow to the long-held national history orthodoxy. Never before had the Indonesian public read a story by a fellow national about the colonial period and the birth of the nation written in such a complex, polyphonic and fascinating fashion. Toer’s novels turn some national heroes into questionable characters, and introduce unknown figures, or recast much despised characters in the official history into heroes. Although Toer’s tetralogy was officially banned soon after its release, it underwent repeated reprints, following the strong demand, from underground sale before 1998, and on the open market after the fall of the New Order government in 1998.

In the decades following Toer’s tetralogy, a few senior authors such as Y.B. Mangunwijaya and Remy Sylado wrote novels dealing with the colonial period and the Indonesian Revolution. These authors were born early enough to have first-hand experience of the period they describe. Iksaka Banu was born in 1964, and was raised during the 32-year militarist authoritarian government of the New Order. This was a period when memory and history of the colonial period and nationalist revolution had been already purged of ambiguity and contradictions. Nationalist ideology was repackaged as militarist indoctrination and made for staple public consumption in mass media, schools, ceremonies, galleries and museums. For all these reasons, Banu’s Semua Untuk Hindia appears like an improbable miracle.

Like Toer, Iksaka Banu conducted some historical investigation before he composed his fiction. Unlike Toer who experienced the long, bumpy and gradual transition from Dutch colonialism into independent Indonesia, Banu had to dig deeper into the few bits and pieces of secondary sources available to him to make some sense of what life was like more than two generations earlier. Banu had never been to the Netherlands until late 2015 when the Tong-Tong Fair invited him to celebrate the success of Semua Untuk Hindia. He did not speak or read Dutch, so he had to rely on a dictionary and consultations with personal friends who spoke the language when preparing his short stories.

Again, like Toer, Mangunwijaya or Sylado before him, Banu had no intention to write history. He fuses his research notes with powerful imagination, wit, humour and surprises. He writes his fiction in a realist mode in Indonesian, sprinkled with European expressions. In the work of many senior Indonesian literary authors who deal with the late colonial period, we see the excitement and dilemmas of the Indonesian protagonists as they encounter modernity from Europe. Banu takes the next step and more challenging task. The first person or the ‘I’ narrator in Banu’s short stories are all non-Indonesians. The outcome is stunning as much as subversive to the official history.

The Colonial, the National

Many Europeans who had personal connections with the Dutch East Indies, and live(d) outside Indonesia tend to nurture fond memories of the colony, dubbed ‘Tempo Doeloe’ (those happy days). Others in the Netherlands have more mixed feelings, but never without a sense of national pride in light of what the Dutch colonial rule did for what is now Indonesia: the vast territory under one state administration; the old and durable infrastructure and preservation of what was claimed as pre-colonial cultures and traditions. Without the great and ostensibly benign work of this colonial rule, there would have been no Indonesia as we know it today.

Contemporary Indonesia has long been trained to internalise the opposite version of history. It is generally understood that Indonesia had existed from time immemorial, and prior to the arrival (or ‘invasion’) of the Europeans. Those Europeans are imagined to have done nothing good for the locals. They were the source of protracted agony to the locals for hundreds of years, before Indonesians took the bloody fight to liberate the nation.

In the official narrative, all whites are lumped together as one social group, called ‘Belanda’ (Hollanders), occupying the most privileged and exploiting class, while all the local natives (‘pribumi’) suffer brutal exploitation, torture and humiliation. The few minority groups (Chinese, Indians, Arabs) are imagined to occupy the opportunistic class of intermediaries in the overall colonial structure of exploitation that victimises the native majority.

Deadly boring as it may sound, the state propagated ethno-nationalism has been in fact widely reproduced by non-state bodies, including the entertainment industry. The most recent examples include the commercially-marketed films: Sang Pencerah (2010, Hanung Bramantyo), Soegija (2012, Garin Nugroho), Soekarno (2013, Hanung Bramantyo), Guru Bangsa: Tjokroaminoto (2015, Garin Nugroho). Not all of them have been highly praised in local reviews, but none has provoked a public controversy for the ridiculous caricatures of persons and events of the past.

Another way of understanding how disconnected the dominant views of the colonialists in Indonesia are from their counterparts in Europe and other English-speaking countries, is to look at the key term of reference. While ‘colonialism’ in English does not entirely refer to commendable or admirable characteristics, it does not entirely refer to the deplorable either. The term has more than one meaning, including area of habitation. Rather than being neutral, in English the term and concept ‘colonialism’ contains ambiguous and contradictory semantic values.

In contrast, the one and only standard term for colonialism in Indonesian is ‘penjajahan’. Unequivocally, it is a term of strong condemnation and indignation. If translated in reverse, ‘penjajahan’ would have the English equivalent of ‘exploitation’. Something is always lost in the translation, but additional meanings and values are highly possible and often inevitable in translation.

Such monochromic sloganeering is shattered in Banu’s witty short stories, just as in Toer’s tetralogy a quarter of century earlier. In the works of both these authors, there are only human beings of various skin colours with familiar contradictory traits, desires and qualities. Good guys and bad guys exist within each, and across diverse racial groups. There are as many conflicts as there are examples of collaboration and romantic love between the whites and non-whites in the Dutch East Indies. Not all whites are Dutch. Not all brown-skinned are non-Dutch. There are many children of racially mixed parents, who fall neither easily into the category of European or native because in reality, they are partially both.

There are as many animosities among the whites, or among the coloured, as between them. Not all whites support Dutch colonial rule. Not all natives oppose it. In Banu’s short story Selamat Tinggal Hindia, a Dutch woman, Maria Geertruida Welwillend, joins the Indonesian armed underground struggle and gives her life for the Indonesian nationalist cause, while fighting the Dutch troops and their allies.

Ill-equipped public

Nearly all reviews of and comments on Banu’s Semua Untuk Hindia have missed the radically subversive character of the anthology. Neither the jury of the Khatulistiwa Literary Award, nor prominent poet and cultural critic Nirwan Dewanto who writes a preface to the anthology, acknowledges these qualities in their musings. Apparently, to this reading public what exists outside the state-sanctioned propaganda is simply unimaginable or incomprehensible.

Significantly, nearly all published comments and reviews refer to the white characters in Semua Untuk Hindia as ‘Dutch’ persons. Actually, the short stories explicitly identify them as Europeans of various nationalities or local-born Eurasians and many of them hate the Dutch. More than a few reviewers grudgingly question why the author has chosen these ‘Dutch’ as protagonists and their voice as the I-narrator. Why not take the voice and perspective of an Indonesian character, they ask.

One reviewer writes in his blog (19 June 2014) ‘[r]egretfully, nearly all the protagonists in these short stories are Dutch, both purely Dutch and Indo (Dutch descent). . . . If only the author gives more space to the native characters, we would have a fuller and balanced picture of East Indies . . .’ Another reviewer in TEMPO magazine (6 October 2014) took issue with such a view, but went on to reproduce the binary opposition between ‘us’ (native Indonesians) and ‘them’, so enshrined in the state propaganda: ‘These stories are narrated not by Indonesians, but the Dutch, the ‘penjajah’ (exploiter/coloniser).

Semua Untuk Hindia is a literary work, not a historical text, or a political challenge to the state propaganda about the past. However, to appreciate the anthology purely as entertaining fiction and to completely disregard its political significance, would be seriously remiss. The anthology is admirable beyond its literary merits, and the power of its political perspective is even more stunning in light of the author’s background. His is from a generation who bore the brunt of the New Order’s indoctrination.

Semua Untuk Hindia is rich with minute details of banalities in the East Indies in the past centuries, with reference to meals, idiomatic expressions, customs, clothing, urban life and warfare. Yet, as commentator Gita Putri Damayana perceptively observes, Banu is not preoccupied with these details. His stories are not held hostage by an exuberant display of exotic and quaint information as has been a trend in a few literary works of his contemporaries.

Specialists of Dutch East Indies history may find faults with the accuracy of some of these details, but I doubt such minor issues would impair the joy of reading the book as fictive tales. Neither would they invalidate my argument about the anthology’s achievements in the non-literary spheres: an act of subverting the societal orthodoxy and liberating the reader from the stultifying indoctrination and propaganda of successive regimes in Indonesia. The fact that many reviewers fail to appreciate this extraordinary achievement only highlights the postcolonial amnesia in contemporary Indonesia.

Iksaka Banu, Semua untuk Hindia, Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia, 2014.

Ariel Heryanto currently investigates Indonesia’s post-colonialism, which includes a study of the Indo-Europeans in the Dutch East Indies.

Inside Indonesia 123: Jan-Mar 2016{jcomments on}