Catherine Smith

Come on over! Acehnese have many reasons to be tempted by Malaysia’s health system - Aceh Magazine

The term ‘medical tourism’ often invokes images of wealthy elites travelling to poorer countries to obtain cheap health care with a holiday to boot. The past decade has seen a boom in medical travel in many parts of the world. Some of Indonesia’s neighbours – such as Malaysia – now actively advertise themselves as medical tourism destinations. Far from catering solely to the wealthy, it has become increasingly clear in recent years that large numbers of poor and lower-middle class people also choose to cross a border to obtain health care.

There are a variety of factors motivating people to make what sometimes seems a surprising choice to travel abroad while ill. Some people seek more affordable health care, others need specialised medical care that is hard to access in their home country, while others choose destinations with shorter wait times or better post-operative support. In all of these situations people recognise the limitations of their own health care systems and make an active choice to travel to a place that can best address their own particular needs and preferences. In many ways, medical travel can be seen as a positive element of globalisation. Cheaper airfares and more porous borders mean that people are able to overcome the limitations of their home country’s health care systems by seeking health care abroad.

However, something that is not yet well understood is the way in which medical tourism affects the health care systems in the home countries of these travelling patients. In particular, how is public confidence in a health care system affected when large numbers of citizens find themselves unable to access quality health care in their own countries and instead are forced to travel abroad? This is a particularly important point to consider when, as in Aceh, medical travel is motivated by a deep-seated discontent and, in some cases, fear of local doctors.

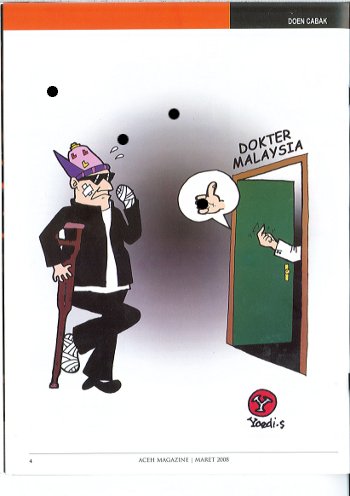

In the post-conflict period, large numbers of Acehnese regularly travel to clinics in Penang and Kuala Lumpur. The close proximity of Malaysia to Aceh, and the rise of budget airlines, makes this travel easy for middle class Acehnese, while many poor Acehnese pool resources so that they can make the trip. Malaysian clinics actively promote this travel, offering relatively affordable and easy to purchase prepaid travel and health care. Many Acehnese people have friends and family living in Malaysia, which also helps.

Many Acehnese believe that Malaysian clinics are more modern, less bureaucratic and the staff friendlier and better skilled than their Indonesian counterparts. Some people travel to Malaysia to manage chronic conditions such as diabetes, while others have checkups to screen for cancer and other diseases that they fear local doctors might have overlooked. Many seek second opinions for persistent health problems that have not responded to treatment in Aceh. What is perhaps of most concern is that many Acehnese seek health care in Malaysia because they do not trust in the ability or the integrity of Acehnese doctors and state-run clinics.

Medicine, health and violence in Aceh

Seven years have passed since the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) signed a peace agreement with the government of Indonesia, bringing an end to almost 30 years of brutal violent conflict. Although many positive changes have occurred in Aceh since the resolution of the conflict, there is much work to be done before Acehnese people fully trust the state. During the conflict (1976-2005) many Acehnese endured extreme forms of violence, including torture, beatings, arson attacks, frequent interrogation and public humiliation. Aceh is also one of the poorest provinces in Indonesia and conflict survivors often emphasise the economic burdens that the conflict added to their already difficult lives.

Through my research with Acehnese conflict survivors, I heard many stories of people avoiding health care out of fear, while others told me that during the conflict years they were refused medical treatment for dubious reasons or no reason at all. I interviewed many people with scars from conflict-related injuries and many told me that they are afraid of revealing these scars to their doctors. For people whose bodies bear physical marks from the conflict, clinical examinations can be traumatic. Many conflict survivors recall loved ones dying during the conflict, not from fighting itself, but because they were unable to access medical care to assist with emergencies such as stroke or complications during childbirth. This memory of loved ones who died due to lack of medical care is fresh in the memory of many Acehnese.

Even after the conflict is resolved many continue to doubt that their doctors have the skills or the will to successfully treat their patients. It is common to hear people question whether local doctors are sufficiently trained. For instance one woman explained to me that endemic corruption meant that she doubted whether a university degree really gives her doctor the skills to practice medicine. ‘The Indonesian government is the most corrupt government in the world’, she protested to me, ‘Can you imagine allowing them to cut open your body?!’

Sadly, many people told me that they doubted whether doctors had good will in their interactions with their patients. I frequently heard people express a fear of dying at the hands of incompetent physicians. Stories of being misdiagnosed, receiving incorrect pharmaceuticals or being unable to access diagnostic technology are common. This becomes complicated again when Acehnese make the short trip to Malaysia and encounter more sympathetic doctors, receive different diagnoses, and access treatment that they perceive to be more modern and of higher quality. Both negative experiences within Aceh and positive experiences in Malaysia contribute to the phenomenon of post-conflict medical travel, and to the widespread criticisms of Acehnese doctors.

Although these public criticisms target doctors in particular, they also indicate broader structural shortcomings in the Indonesian health care system that affect many other Indonesians. While there have been significant increases in the health budget over the past decade, the World Bank reports that Indonesia has a shortage of doctors and continues to lag behind many of its neighbours on a number of health indicators. A new hospital was built in Banda Aceh after the Indian Ocean tsunami, but there continues to be a shortage of doctors, and Aceh’s predominately rural population relies heavily on nurses and midwives for primary health care. Within Banda Aceh too, it is common to hear people complaining of being unable to access diagnostic technology, so that travel to Malaysia becomes necessary. There is also a common perception that the pharmaceuticals circulating within Indonesia are outdated, poor quality or counterfeit and essentially ineffective.

The structural problems with the Indonesian health care system are, of course, concerning in themselves. These health inequalities are also apparent to ordinary Acehnese people, many of whom recognise that some of the illnesses that are common in Aceh are easier to diagnose or cure in places with better health care systems. For example, Acehnese know that Malaysians are more likely to be able to access technology to have an earlier diagnosis of cancer. When they return from Malaysia and tell others of their encounters with ‘friendly’ and ‘intelligent’ Malaysian doctors, Acehnese depict the disparities between the Indonesian and the Malaysian health care systems as a form of injustice. As medical travel becomes more accessible to poor and middle-class Indonesians, the regional health disparities that have long been noted in statistical reports are becoming increasingly apparent to ordinary people.

The practical and symbolic importance of doctors

The practice of Acehnese medical travel to Malaysia reveals problems in the Indonesian health care system that are not readily apparent through health statistics alone. The bottom line is that many Acehnese people simply do not trust their doctors. While it is important to continue developing health infrastructure, it is vital not to underestimate the importance of rebuilding public confidence in the health care system. People’s health suffers greatly when state institutions become a focal point of fear. This is most evident in situations where people delay seeking health care because they have lost faith in the credibility of doctors.

While medical travel to Malaysia enables many Acehnese to access much needed health care, it also provides a dramatic contrast to the Indonesian health care system, sets the benchmark for desirable health care at a very high level and reinforces this public criticism of doctors. Medical travel is a good option for Acehnese seeking health care, at least for those who can afford it. However it is no substitute for building an efficacious and trusted health care system accessible to all local people who need it.

Catherine Smith (cat.catherinesmith@gmail.com) is a medical anthropologist researching trauma and healing in Aceh.