Rebekah E. Moore

Navicula performing their song Orangutan during a concert in Ubud, BaliAlfred Pasifico Ginting |

During the New Order, the widespread censorship of journalism, broadcast media and literature aimed to stifle subversive social movements. Popular music, however, was largely underestimated for its galvanising power. Popular artists like Iwan Fals and Sawung Jabo penned the era’s most renowned protest songs, illuminating social injustices like greed, corruption and unfair wages, and calling attention to the nation’s underclasses, from street children to prostitutes. Iwan Fals, in particular, gave a voice to the nation’s poor and disenfranchised, and – despite a brief arrest and numerous bans on public performance – was instrumental in defining the rock musician’s role as social activist in Indonesia.

Present-day rock band Navicula follows in Iwan Fals’s footsteps, combining songwriting, performance and street activism to draw attention to Indonesia’s societal ills. Environmental crises form the primary focus for the self-proclaimed ‘Green Grunge Rockers’. The Bali-based grunge/psychedelic rock outfit does not appeal to all Indonesian music fans, but has remained at the forefront of Indonesian music activism for much of its sixteen-year career. Most recently, through the use of social media, Navicula has uncovered a new platform for publicising the nation’s political, environmental, economic and social injustices.

Musical activism online and offline

Navicula has made creative use of social media and the internet to disseminate its social justice messages. Utilising open source technology, the band often releases its most condemning protest songs for free download on their official website, cross-promoted on its heavily trafficked Facebook and Twitter profiles. In 2009, for example, the band released the song Mafia Medis (Medical Mafia) for free download in response to the arrest and imprisonment of Tangerang mother of two, Prita Mulyasari. Navicula also joined dozens of recording artists who used online social media to criticise her arrest and raise funds for the Coin for Prita campaign (see Dibley, this edition). According to Navicula front man, Gede Robi Supriyanto, the band hoped free access to Mafia Medis would support this movement by making it known to a larger audience.

Navicula also uses social media to publicise its political causes by participating in music competitions that use online voting. In June, Navicula submitted a music video for Metropolutan (Metro-pollutant), a song decrying Jakarta’s pollution crisis, to the worldwide band competition, the Next Røde Røckers. Navicula was among ten bands selected by a panel of expert judges to compete in finals, ultimately winning a recording contract at Record Plant in Hollywood, which it will take up in November, and a two-year equipment endorsement from Røde Microphones. By the end of the competition, more than 23,000 people had viewed the Metropolutan clip on YouTube.

Navicula also uses social media, as well as other online tools, to help raise awareness – and funds – for forms of offline activism, including community action and charity concerts. In 2011, Robi and Navicula manager, Lakota Moira, co-founded an environmental news media source called Akarumput.com. The magazine publicises urgent environmental issues such as poor waste management, water shortages, agricultural genetic engineering and overdevelopment. Akarumput also hosts community events, ranging from permaculture workshops to eco-awareness music concerts. Last October, in partnership with the Bali International School and members of the visual artist collective Komunitas Jamur, Akarumput created an 80-metre-long eco-mural on a concrete wall bordering a crowded neighborhood street in southern Denpasar. The night the mural was completed, Navicula joined several Denpasar-based rock bands to perform a free concert in the parking lot opposite the newly painted wall.

Social networking has also led to valuable partnerships. Earlier this year, Navicula released Orangutan, a song predicting the ultimate demise of Indonesia’s red apes as a result of deforestation. An accompanying music video, released on YouTube, caught the attention of Greenpeace Indonesia’s deforestation action team Mata Harimau (The Eye of the Tiger), anti-palm oil nonprofit Sawit Watch, and national environmental forum WALHI (Friends of the Earth Indonesia). Aiming to take its activism to ground zero, the orangutans’ dwindling habitat in Borneo, the band partnered with these environmental watchdogs to complete a two-week trek by dirt bike through central and west Kalimantan.

|

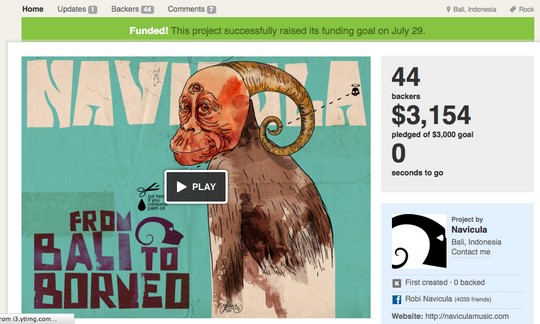

Screenshot of Navicula’s Kickstarter campaign pagehttp://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1637792006/golden-green-grunge-for-rare-red-apes-navicula-bor/?ref=kicktraq |

Navicula subsequently launched a ‘Tour to Borneo’ Kickstarter campaign, using this popular crowdfunding website to raise the money needed for the band’s travel expenses to Kalimantan. Through exhaustive campaigning on Facebook and Twitter, as well as public appearances in Bali and Jakarta, Navicula rallied enough supporters (or Kickstarter ‘backers’) to surpass their fundraising goal of A$2860. The tour, named after the endangered Kalimantan hornbill ‘Kepak Sayap Enggang’, included meetings between Navicula and marginalized Dayak communities in conflict with mining companies and palm oil plantations in the region, facilitated by the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples Archipelago (AMAN). Throughout the tour, the band web-released video logs documenting their encounters, created by noted filmmaker Rahung Nasution.

Limits of a radical agenda

Despite these successes, the band remains on the periphery of the nation’s music industry. A number of rock music acts surpass their online popularity. Punk band Superman is Dead, for example, boasts a staggering 3.2 million fans on Facebook and nearly 131,000 Twitter followers. In second place are arena rockers Slank, with 2.6 million Facebook fans and 121,500 Twitter followers. Navicula, by comparison, has accumulated an audience of only 23,500 on Facebook and 9500 on Twitter. Robi suspects these lower figures are because the dogged social criticism of such ‘far left’ groups as Navicula may be too sombre or controversial for the average Indonesian rock fan. Superman Is Dead and Slank have also intermittently taken on social and environmental issues. Superman is Dead organises beach cleanups and Slank openly backs the nation’s Corruption Eradication Commission. But neither group has used their lyrics or online commentary to address social and environmental justice issues as persistently or precisely as Navicula.

Additionally, while Facebook and Twitter were instrumental in helping Navicula publicise its Kickstarter project, Robi cautions that online social networking cannot replace public appearances. In fact, following a public presentation on orangutan conservation in Ubud, Bali, Navicula raised 40 per cent of its total funds overnight. While the fundraising campaign was launched online, in this case, Navicula’s offline appearances - rather than concurrent online social media campaigning - were ultimately more valuable for rallying public support in the form of monetary donations.

Nevertheless, Navicula’s online presence is vital to its success. The band may not have as many online followers as some of its contemporaries, but it has succeeded in using social media to motivate social and environmental engagement among Indonesia’s youth. In making savvy use of Facebook and Twitter as rallying tools, Navicula not only gained an international audience for its activism, it also advanced the historical relationship between rock music and social critique in Indonesia.

Rebekah E. Moore (reemoore@indiana.edu) is a doctoral candidate (Indiana University) and public ethnomusicologist, working in Bali as Music Productions Manager for BaliSpirit Group. She is also a contributing writer and at-large editor for alternative environmental news source Akarumput.com.