Joanne Morton

Ibu Yuliana collects cassava for breakfast every morningJoanne Morton |

Ibu Yuliana and her family live in the rural village of Lempo in Tana Toraja. Her days remain busy even though her four adult children now live away from home. She and her husband are subsistence farmers, and grow their own rice, coffee and vegetables. They produce enough to put food on the table but seldom enough to make a profit, so they rely on their eldest son to send them money to supplement their income. Like most of Indonesia’s low income population, this means that it is almost impossible for them to save money to cover large expenditures such as education for all their children.

But things looked up for Ibu Yuliana last year when she was among a group of women who received a National Program for Community Empowerment (PNPM) loan from the local government. Most micro credit programs focus on income-generating activities, but PNPM loans are very flexible. Ibu Yuliana used her share to finance home improvements and pay her three daughters’ fees at a local university. She then pays back the loan from the money she receives from her son every two months.

The PNPM program

PNPM is a national government program that was initiated in 2007 with the aim of alleviating poverty through community driven micro credit initiatives. Now PNPM loans are available in poor communities where no other form of financial assistance is accessible. Groups of women of ten or less can apply for a loan based on a ‘shared purpose’. In order to be eligible, applicants must be willing to participate in monthly meetings and be a local resident. The PNPM program is pro-poor, and applicants are assessed on their ability to make repayments rather than their level of assets.

The micro credit scheme began in Tana Toraja four years ago, and the number of participants has doubled each year. Women’s groups have typically applied for the loans to provide capital to start a small foodstall, to buy a pig or seeds for their garden, or to pay for their children’s education. According to Pak Medin, the local government PNPM facilitator, the repayment rate in the region is very high because the women feel a collective responsibility, which encourages the group members to fulfil their obligation to repay the loan.

The loans, which range between Rp.300,000 and 1,000,000 (A$33- A$112), must be repaid within six months at a 12 per cent interest rate. If the loan is not repaid within this period, the group is banned from applying again to the scheme in the near future. As the majority of the loans are for non-income raising ventures, such as school fees, or home improvements – as in the case of Ibu Yuliana – they are often paid back with the remittances received from family members working elsewhere.

Savings schemes

|

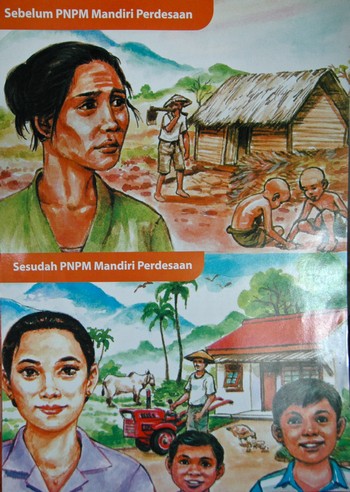

A government campaign promotes the PNPM programJoanne Morton |

In other parts of Sulawesi women supplement their household income by participating in NGO-sponsored savings schemes. One such a scheme is organised by local women’s groups in five major provinces in South Sulawesi that are part of Jaringan Perempuan Usaha Kecil (JarPUK). When these groups were first established in 1987, they operated as forums to raise awareness about gender sensitive issues. In 2000 they began to implement district level saving schemes, funded by the NGO Lembaga Mitra Lingkungan (LML). Today the savings schemes constitute the JarPUK groups’ most successful program.

The JarPUK savings scheme has two elements. The first is a classic ‘arisan’, a savings scheme based on a lottery system, with each woman contributing a small amount of money every month to a pot. The collected amount is then ‘won’ by a different woman based on a monthly roster. Like the PNPM program, the only requirements for membership are that women are willing to attend regular meetings and that they are local residents. Unlike the loan scheme, however, women do not need to apply and, because they use their own money, there are no formal repayments.

JarPUK also organises a collective savings scheme, with each woman in a group contributing a small amount which is then deposited into the community bank. Funds can later be loaned to members to be used as start-up capital for a small business. The most successful enterprises funded by the scheme have been some of the smallest. One woman bought make-up in bulk with her start-up capital, and then sells this to other women who find it difficult to the leave the village, making a small profit in the process. Another group borrowed money from the collective to set up a small business making cakes and snacks which are sold at a kiosk in the village.

As part of these schemes JarPUK also offer information and training sessions, with topics including household budget management, health and sanitation, organic fertilisers, and sales techniques ‘from farm to market’. The organisation argues that their training increases women’s decision making and leadership skills. According to one participant I spoke to, the savings schemes are empowering as they enable women to have some degree of control over their family finances. She noted that women’s capacity to contribute to the household income through their participation in the arisan or by starting a small business makes husbands realise over time that their wives can manage the household’s income.

Loans for the future

Whether microfinance schemes are provided by the government or NGOs, they lead to the same outcomes. The schemes help low income households like Ibu Yuliana’s stretch their limited resources to improve their situation. And the benefits of the schemes are not confined to economic gains. They also empower women to manage household finances and give them a voice.

The loan schemes are also having a positive effect on future generations of Indonesian women. Ibu Yuliana’s three daughters have access to a higher level of education than they could have had if she hadn’t had access to a PNPM loan. The daughters of women who establish businesses using capital from the JarPUK collective savings scheme have strong mothers as role models, who can inspire them to take charge of their lives. It is with these small steps that microfinance schemes are helping poor households achieve changes that will make a big difference in the longer term.

Joanne Morton (jmor4517@uni.sydney.edu.au) is an undergraduate student majoring in Anthropology at the University of Sydney.