Benjamin Hegarty

Situated between poverty and wealth, modernity and tradition, history and the future, Indonesia is in the midst of rapid change. The people affected most by this situation are the country’s poor rural migrants who have moved to the cities in search of success. Living in the shadows of conspicuous wealth and modernity, they are rarely represented as active agents framing and reframing their identities in the context of globalisation.

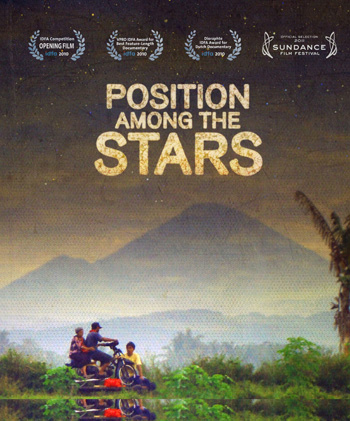

Position Among the Stars (Stand van de sterren) is the final film in a documentary trilogy by cinema verité filmmaker Leonard Retel Helmrich, which delves into the troubling themes of globalisation, modernity, tradition and social conflict from the perspective of Jakarta’s urban poor. In literature and film the lives of the poor are often framed by two things – middle class apathy or government representations – which focus on the victimhood of the poor. This documentary-style exploration of an Indonesian family breaks out of these two frames by exploring the complexities and agency of those on the periphery of Indonesian society with a humanistic lens.

This is verité film-making at its best. Written without narration or voice-over the performance of the Sjamsuddin family, poor migrants from rural Java, is captivating and emotionally raw. The family is at ease in front of the camera, allowing the audience to share in the metaphorical and literal journey that is life at the margins.

Journeying from the margins

Position Among the Stars portrays life lived in the space between the rural periphery and the postcolonial and postmodern urban centre. It highlights the schism between classes that continues to afflict Indonesian society, particularly the frustration of being surrounded by wealth but not being allowed to share in it. Helmrich follows the family as they attempt to make the considerable leap from Jakarta’s vast poor to its growing middle class. The pressure of this desire is felt most acutely by the family’s adopted daughter Tari, whom the family seeks to push through university by any means possible.

The film chronicles grandmother Rumidjah’s return journey from her hometown in Central Java to urban Jakarta to help her son look after Tari. The pressure placed on Tari to succeed is immense and the family’s intense effort to succeed economically frames the entire film. Conflict within the family under strain is carefully portrayed, starting from the restlessness caused by the move from the countryside to the city, but also the day-to-day struggle for survival that characterises life in the city. Bakti, the son, works as a neighbourhood watchman and, despite Rumidjah’s suggestion that he solicit bribes, he earns very little. Bakti focuses on breeding fighting fish for gambling, which he thinks will make him rich, whilst his wife sells food out of their home. Informal employment such as this characterises the way that many lower class Indonesians survive economically. The film highlights how precarious this way of living is for Jakarta’s urban poor.

A desire to escape this marginal position is the reason for the immense pressure her family puts on Tari to make it through university. They are willing to get her through at any cost. In the end the family place their house as collateral for a loan for college fees. Tari seems relatively resilient in the face of such pressures; however, as she is exposed to more consumerist and western values and desires, she begins to drift away from her family. The subtle contradictions between the family’s plans for Tari and their lack of understanding of the changes taking place in her worldview, is not only tragic but representative of wider societal fractures.

A meditation on dark and light

Helmrich gives a wonderful sense of the grittiness of everyday life for Jakarta’s city-dwellers; the dreams that they hold; and the historical and contemporary frameworks that inhibit them. For the family, Indonesia is a place of hope. Despite living on the poverty line, rapid (though uneven) economic growth and a spectacular (if messy) democratisation process provide the setting for an environment where the stars feel within reach.

The theme of poverty and its causes is unquestionably bleak. But Helmrich presents us with a film brimming with empathy and humour, drawing viewers into a sense of understanding about Indonesian society, which is difficult for outsiders to achieve. The scenes of Rumidjah interacting with her rural friend Tumisa upon returning from Jakarta are touching and funny, particularly where she tries (unsuccessfully) to show her how to use a gas cooker which Tumisa dismisses as ‘newfangled technology for city-folk’, preferring to collect wood to light her fire for cooking, describing it as ‘exercise’ which keeps her fit and healthy.

Other scenes playfully derive a sense of beauty from the otherwise bleak environment of the Southeast Asian metropolis. The spectacular sequence of a boy ‘flying’ through the narrow alleyways of the Jakarta as bundles of money flutter through the air is cinematographically and emotionally powerful. It is through scenes like these, which provide a narrative on the dislocating process of modernisation in developing countries, that the film succeeds spectacularly. For example, the beauty of the dialogue between Rumidjah and her friend Tumisa, which debates the merits of materialistic consumer society, provides us with an understanding of the resilience and agency of Asia’s poor.

The least convincing theme in the film is the portrayal of religious conflict in Indonesia, where a rather simplified and unfair representation pits Islam against Christianity. Despite featuring in the socio-economic landscape of the country, religion in Indonesia is by no means as simple as Helmrich sets out. The result is unconvincing and feels out of step with the otherwise sharp and incisive commentary on contemporary Indonesia that the film presents. This portrayal of religious conflict (including dramatic shots of a mosque’s minaret rising above a church’s cross and wonderful footage of a rally of the Islamic Defenders Front) seem to be more a product of contemporary European fears over globalised Islam than an accurate rendition of its role in the context of social and cultural change in Indonesia.

The urban poor from below

The film provides a stylish and watchable perspective on the urban poor through the lens of a filmmaker who knows his subject and their struggles well. Helmrich has worked with the Sjamsuddins for many years and the film’s personal connection with the family is clear in its empathetic and emotional portrayal of their plight.

Often seen only from the highway or high-rise buildings of Asia’s ever-changing metropolises, its poorest neighbourhoods are bursting with stories like this; of people eager to realise their potential through economic success. Tragically, their poverty puts them a universe away from the shiny high-rises and expressways which seem just within reach.

‘There isn’t a government in the world’, Bakti shouts during an argument about Tari’s school fees, ‘that looks after its people’. Such is the sense of loneliness and frustration of Indonesia’s poor, who feel betrayed by their government and by the failure of globalisation to provide for different paths to ‘modernity’. Helmrich’s inspirational Position Among the Stars helps to sharpen our focus on the inequality that plagues the developing world and the urgent need to address it.

Benjamin Hegarty (Benjamin.hegarty@student.monash.edu.au) is a graduate student at the Monash Asia Institute in Melbourne. He has worked with Indonesia’s national indigenous peoples’ organisation (AMAN) in Jakarta and writes on cultural politics in the archipelago.