Graeme MacRae

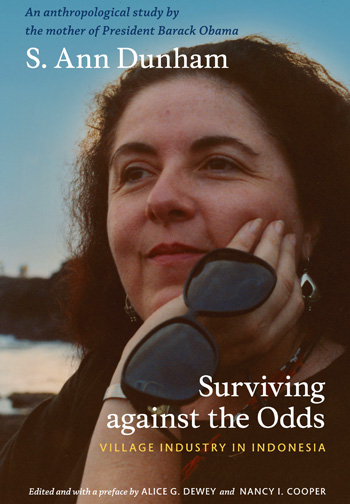

It is no wonder US President Barack Obama is managing to survive against the odds. His mother, S Ann Dunham, would have been a good teacher, but also a hard act to follow. The title of this book refers neither to Obama nor his mother, but to the people she worked with in Indonesia, mostly when he was a child. Surviving Against the Odds is the book based on Dunham’s PhD thesis from the University of Hawaii, which all academics mean to write but don’t always get around to. Her work with them was anthropological, but it was mostly conducted in conjunction with work for Indonesian government and foreign aid agencies, on various projects for development of rural industries and livelihoods, from the late 1970s until the early 1990s. Dunham started work on it too late (she died soon after), but the task was taken up and completed by a team led by her academic mentor Alice Dewey. In the euphoria following her son’s election as President of the USA, Duke University Press had the vision to see a publishing opportunity. As a work of anthropology it is unusual, interesting and inspiring, but I want to concentrate here on its significance for Indonesian studies.

Real work

This is a book about the craftspeople who make all those wonderful everyday things you see in markets all over Indonesia: farm implements, carpenters’ tools and kitchen utensils, baskets and birdcages, pottery, puppets and batik. It is essentially an in-depth study of the practices and traditions of village blacksmithing, and the challenges such small industries face in a rapidly changing economy, which focuses primarily on one village an hour or so east of Yogyakarta. It takes us into the life of that village and minute details of the social organisation and economics of the workshops in which recycled scrap steel is transformed by heat and hammer into tools of various kinds. In the initial chapters we meet the smiths, their families, neighbours and trading partners. We learn about the different tools and how they are made. We smell the heat and smoke, the dust and mud. We see how some master smiths become wealthy and powerful through building up trade networks, while others remain humble employees all their lives. We start to see the ways in which village handicrafts, livelihoods and ways of life are being marginalised by the combination of economic modernisation, urbanisation and government policies which privilege large industries over small ones.

But Dunham also zooms outward from the level of village and workshop, in several ways. She explains the flows of raw materials (scrap steel, charcoal, tools), finished products (hoes, knives) and money (payments, debts, profits) between suppliers, producers and consumers spanning distant villages and towns and agricultural districts. She also examines a range of statistical data locating village blacksmithing in the larger contexts of the metalworking industry and the entire national industrial system. This particular chapter is not light bedtime reading, but what it provides is the understanding necessary for well-informed government policy or development assistance. She also considers government policy itself and reviews a range of interventions and their effects at the village level. In her concluding chapter she makes recommendations for future policy.

Most writing about Indonesia tends to work either at the micro-level of villages and neighbourhoods or of national economic and political patterns and processes. There is a parallel split between those books which take us into the rich sensory experience of Indonesia and those which limit themselves to often rather dry academic analysis. The beauty and value of Surviving Against the Odds is that it does both and more importantly it makes the connections between these levels and styles of description and analysis. This brings us to the deeper aims and argument of the book.

Real people

What Ann Dunham is trying to show us is at once the richness and complexity of village handicraft traditions, but also that their practitioners are not living in either a romanticised traditional world nor mired in the stagnant rural economic backwaters. They are real people, many of them highly innovative profit-driven entrepreneurs who are not only surviving, but thriving in an environment where they have few competitive advantages. She argues convincingly that village industries are not anachronistic relics of the economic past, but have the potential to provide a sustainable base for rural livelihoods which are otherwise undermined by modernisation and urbanisation. This is the basis of her plea for better policy and development practice informed by local realities and oriented to supporting them.

Research of this depth, breadth and subtlety was rare in its day, and is even less easily achieved in the brief visits that most contemporary foreign researchers are able to make. It is a model for new researchers to aspire to. What Ann Dunham also provides, is a model for an engaged, committed way for foreigners to live in Indonesia and make a contribution that links many levels of society not easily bridged by many Indonesians themselves.

Much has changed in Indonesia since Dunham’s research. She wrote of the two greatest threats to village industries as ‘deregulation and mechanisation’. Both of these have since come to pass, and combined they have led to a growing flood of imported (mostly Chinese) steel tools which can be found in any supermarket. I am not aware of the effects of this on the blacksmiths of Dunham’s villages, but this would make a good topic for new research and her footsteps would be inspiring ones for a young researcher to follow.

S. Ann Dunham, Surviving Against the Odds: Village Industry in Indonesia, Duke University Press, Durham, 2010.

Graeme MacRae, (G.S.Macrae@massey.ac.nz) teaches Indonesian studies and anthropology at the School of Social and Cultural Studies, Massey University, Auckland.