Stuart Upton

In the second of two pieces on demographic change in Indonesian Papua, Inside Indonesia here presents an analysis by Stuart Upton that suggests – in contrast to the first piece written by Jim Elmslie – there is little hard evidence to support claims of genocide in Papua.

The indigenous population of Papua has resisted Indonesian control from the start. Since the Dutch passed sovereignty over Papua to Indonesian hands in 1963 there has been recurrent violence in the territory, resulting from the heavy military presence there. The armed forces have committed many human rights abuses. These are well-documented and indisputable. What is problematic is how these and similar experiences are interpreted. Many people have claimed that this violence, along with attacks on Papuan culture and social structures, constitutes a program of genocide against the indigenous population. This emotive term has been widely used by both indigenous and Western activists in the last few years. However, the case in favour of using the term genocide to describe the Papuan situation is weak. It is also potentially damaging to the cause of positive change in Papua.

Demographic change

One of the common charges is that the Papuans are subject to genocide by stealth, in the form of migration by non-Papuan settlers. Through looking at the figures on lifetime migration and religious affiliation, the broad patterns of demographic change can be discerned. While there were issues with the coverage of the 2000 census, there have not been any substantiated claims that the statistical data have been manipulated for political reasons, and these figures remain our best guide for understanding population trends in Papua (by which I mean the two contemporary provinces of Papua and West Papua).

If there was genocide in Papua, we would expect the number of Papuans to be declining. The 2000 census recorded ethnic composition of the population, showing there were 1,460,000 Papuans in the province, up from 890,000 in 1971. The yearly growth rate of 1.7 per cent is only marginally less than that of Indonesia as a whole of 1.8 per cent. While Papuans made up only two-thirds of the province’s population in 2000, their numbers are only decreasing in relative terms.

The case in favour of using the term genocide to describe the Papuan situation is weak, and it is potentially damaging to the cause of positive change in Papua

Much of the eastern part of the archipelago, of which Papua is one part, has experienced significant economic development over the last three decades, prompting large numbers of migrants to move to these areas of growth using the improving transport system. Between 1971 and 2000, the population of Papua increased from just over 920,000 to nearly 2,440,000. This is a seemingly large increase but it is a population growth of only 3.1 per cent per year over these three decades, this rate being lower than other provinces in eastern Indonesia such as East Kalimantan (4.2 per cent) or Southeast Sulawesi (3.2 per cent). Papua is also not the only province to experience high levels of immigration, with the percentage of lifetime migrants in East Kalimantan in 2000 (35 per cent of the population) being far higher than in Papua (20 per cent). Put in their broader Indonesian context, population changes in Papua don’t look like genocide, they just look like part of the normal pattern of inter-island migration.

Papua is also not the only province to experience high levels of immigration, with the percentage of lifetime migrants in East Kalimantan being far higher than in Papua

Migration was an important factor from the first few years after the Dutch left and the Indonesians took over. Initially there was an influx of Indonesians taking the higher level public service positions. By 1971 there were over one thousand tertiary educated Indonesians in the province (mostly from Java) compared to less than 100 Papuans educated to this level. This was a blow for the Papuan elites because the government was the dominant employer. There were also some transmigrants settled in Papua prior to the so-called Act of Free Choice in 1969 (surely an indication that Indonesia had every expectation that the vote would go the way they intended).

Transmigration and military violence

There were relatively low levels of migration through the 1970s, unsurprising for such a remote part of the nation, with the 1980s bringing settlers from Java due to increasing transmigration projects. The figure of 90,000 migrants in 1980 rose to 260,000 by 1990. The settlement of transmigrants along the PNG border was a government attempt to cement the incorporation of Papua into the nation. Since then, transmigration has ceased to be a major factor in demographic change. The importance of this program diminished in the 1990s with the rising number of self-financed migrants from Sulawesi and Maluku taking advantage of the improving shipping system. It is hard to accurately estimate the proportion of migrants who have arrived through the transmigration program but they probably represent less than a third of migrants overall. The transmigration program was finally halted in 2000.

Instead, the great majority of newcomers were not part of the transmigration program and came to settle in the towns and cities along the coast with little or no government assistance. The chief force bringing them to Papua has not been government policy but instead pull migration for economic reasons, with the migrants mainly coming from eastern Indonesia, particularly Sulawesi and Maluku. In urban areas, migrants from these areas made up 23 per cent of the population compared to 12 per cent from Java in 2000. The impression on the ground is that the proportion of migrants from Eastern Indonesia is rising.

Another common accusation is that the Indonesian military has been responsible for so many attacks on the population that they amount to attempted genocide. But genocidal actions would be expected to lead to gaps in the population statistics such as missing men in particular age groups. My analysis of the figures from all the censuses carried out in the province shows no evidence of such gaps. There are low male-female ratios for the 20-29 year age group but these low ratios do not carry over to older age groups in later censuses. It seems that young men are simply not being counted in the census, possibly due to their avoidance of government agencies or through difficulties in the administration of the census. Similar issues with counting young men were encountered by the statisticians in charge of the latest census in Britain.

Genocidal military actions would be expected to lead to gaps in the population statistics, but my analysis of the figures from all the censuses carried out in the province shows no evidence of such gaps

For particular ethnic groups who have been the victims of violence from the military, such as the highland Dani, the 2000 census did not show evidence of men missing on a large scale. Additionally, there are no large decreases in population figures in particular districts which would point to massacres of whole villages in these areas. All this is not to deny that there have been serious human rights abuses, but it seems they have not been on such a scale as to leave their mark on the population records.

Explaining the charges of genocide

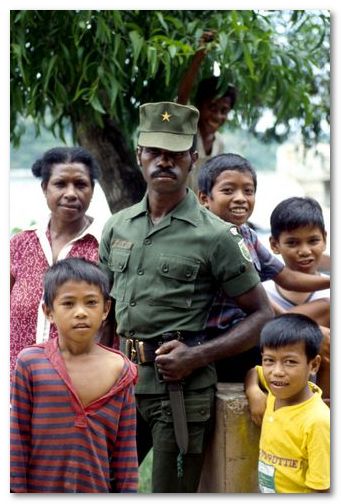

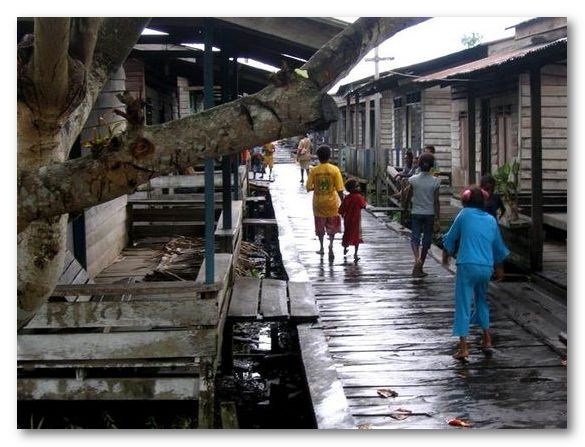

|

A glimpse of houses in the transmigrant settlement in Babo Bintuni, founded 23 years agoIskandar Nugraha |

The figures show that many of the provinces across Eastern Indonesia have experienced massive demographic change, change that has impacted greatly on the indigenous populations. So why are there suggestions of genocide in Papua but not in East Kalimantan or other eastern provinces? The reasons behind this are complex but involve the lower level of commitment to the Indonesian nation felt by Papuans, partly as a result of the separation of Papua from the new nation of Indonesia following the Pacific War. With the Dutch holding on to this half of New Guinea until 1962, an indigenous elite with an expectation of separate independence was born. The dashing of this hope by the Cold War politics of the time created resentment and little commitment to Indonesian nationalism.

There is also a subtext of racism implicit in much of the discussion of the genocide issue from both sides. Papuans suggest that they could never be part of Indonesia due to differences in skin colour (they are dark, Indonesians are light) or hair type (they have curly hair, Indonesians have straight hair). Such reliance on physical appearance in marking national identity – a racialist assumption of a sort that is repudiated these days in many parts of the world – is itself a response to the negative attitudes, including racist stereotyping, that many Indonesians show towards Papuans.

The charges of genocide also stem from Papuan social disadvantage. Migration patterns have indeed contributed to this disadvantage. The influx of economic migrants has impacted greatly on the indigenous populace, blocking them from gaining better education and employment in the coastal towns. Only one in five migrants in these towns are from another area of Papua, with the rest being migrants from outside the province. With most industries located along the coast, the better-educated migrants settling in these areas have tended to get the jobs in higher status sectors. For example, in the cities non-indigenous people are four times more likely to have jobs as traders than indigenous people. Overall, migrants hold more than 90 per cent of the lucrative jobs in trading.

The figures for rural areas are even more striking, with non-indigenous people being 16 times more likely to work in the trade sector than Papuans. Ethnic connections are important for getting jobs in Indonesia, and in helping migrants to establish themselves in towns. With few indigenous businesspeople, Papuans can’t use ethnic affiliation to obtain employment. The indigenous population continues to work in agriculture in rural areas, with the majority still in subsistence farming and only peripherally engaged with the modern economy.

Along with the majority of employment possibilities, the coastal urban areas have the best education opportunities. Illiteracy is only four per cent in the migrant-dominated capital Jayapura but it is nearly 60 per cent in the rural highlands of Jayawijaya. Migrants are more than twice as likely as indigenous people to have finished secondary school, and five times more likely to have tertiary qualifications. The poor standards of education in the areas where Papuans live, the distances between villages and schools (especially secondary schools), and financial obstacles to regular school attendance mean that many indigenous children do not obtain the education necessary to compete for employment.

The results of all these factors are that indigenous people have little chance of migrating to the towns, are unable to compete in the job market and do not see their children getting an education that will enable them to compete in the future. Rather than simply being the result of human rights abuses in the province, the current sense of a shared Papuan identity is more the result of the marginalisation of the indigenous people, and the understandable resentment and jealousy felt by this group towards the economic success of the newcomers.

With little realistic prospect of independence, working with the Indonesian side to implement policies to reduce corruption and the power of the military in Papua would be a vital first step to create trust in the government among the indigenous population

With little realistic prospect of independence, working with the Indonesian side to implement policies to reduce corruption and the power of the military in Papua would be a vital first step to create trust in the government among the indigenous population. In the longer term, policies to address the poor education standards of Papuans, assist indigenous small-businesses and enable more equality in employment are needed.

The claims of genocide in the province are mistaken and misleading. Such dramatising of the situation in Papua is only likely to result in the alienation of those Indonesian groups who are in a position to implement meaningful change. The ‘Papua Road Map’ drawn up by the Indonesian Institute of Sciences suggests that some in the Indonesian academic community are willing to embrace such change. Let us hope that there are those in the bureaucracy and the military who can do the same in the future. ii

Stuart Upton (suptons@optusnet.com.au) completed his PhD about migration in Papua at the University of New South Wales in 2009.