Julian Millie

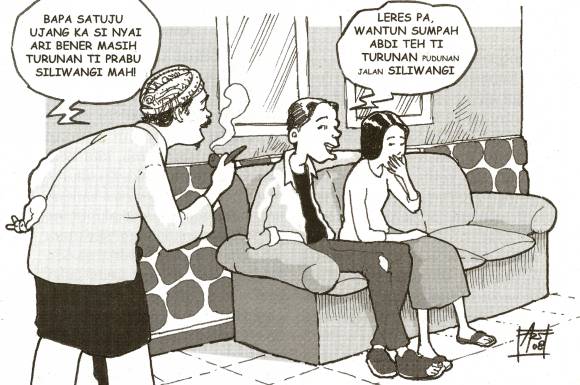

Man with pipe: Lad, I agree for you to be with my daughter if it is true that you are a descendant of [ the legendary Sundanese ruler] Siliwangi! |

The regional languages of Indonesia developed within social systems that have little resemblance to those of contemporary Indonesia. The speech levels preserved in languages such as Javanese and Sundanese, for example, allow expression of relative positions in a social hierarchy defined by birth and other markers. This hierarchy is not something most Indonesians want to reproduce in contemporary society. As a result, aspects of these languages occasionally clash with the realities of day-to-day life.

Some features of the Sundanese language reflect the hierarchical societies of Indonesia’s past. One young Sundanese scholar has set himself the task of resolving this problem.

Iwa Lukmana is a member of a generation of young Sundanese scholars interested in harmonising Sundanese with the communication needs of contemporary Indonesians. He has written a series of articles in a Sundanese language magazine, Cupumanik, that question the feudal legacy of the language. In a recent article, for example, he discussed the Sundanese custom known as mancakaki, which literally means to establish relations and linkages between people. Sundanese people use this term in a number of contexts. When a ritual specialist makes a speech at the beginning of a ritual meal, for example, he takes care to mention the names of the deceased members of the host’s immediate family. The relations binding the host to the names invoked are called pancakaki (the noun form of mancakaki).

This meaning is not the one Lukmana is interested in. Mancakaki is also a social convention that Sundanese find useful when communicating with strangers. When two people who do not know each other meet, they ask each other questions about their origins, place of residence and so on. In this way, they identify common points of reference that make communication easier. For Lukmana, this type of mancakaki brings to the surface important questions about social relations in contemporary Indonesia and West Java in particular.

How are we different?

Originally, the custom was intended to ascertain familial and kinship identity. But it has expanded to include points of reference of many kinds. On the positive side, it allows Sundanese to establish a sense of mutual solidarity through recognition of commonalities. For Lukmana, however, the custom has a negative side. He points out that when people mancakaki, they establish not only common points of reference according to Sundanese convention, but also points of difference.

Knowledge of these differences, according to Lukmana, introduces hierarchical considerations into the relationship. Sundanese people automatically slip into relative positions after establishing their pancakaki. The two conversationalists may be from the same village, but once it is established that one speaker was born in an elite home, or that he or she comes from a line of high office-bearers, the other will assume an inferior position. The ‘inferior’ speaker will adopt body language, such as stooping in respect, or linguistic tools, such as deferential pronouns, that express his or her inferior position in the social hierarchy.

Another negative side of mancakaki is that it detracts from the substance of conversations. After relative status is established, the speakers’ efforts are directed towards honouring the status difference. As the emphasis shifts from substance to recognition of the hierarchy, the conversation becomes an exercise in power relations. The result of this is that people of lower status often fail to communicate important meanings, or alternatively, the substance of what they say will be ignored.

A Sundanese language for a modern Indonesia

For Lukmana, who currently lectures at the Indonesian University of Education (UPI) in Bandung, these are important matters. He sees the Indonesian present as a period of democracy, which implies equality and tolerance between Indonesians. By contrast, the custom of mancakaki, along with other Sundanese speech conventions such as the use of different speech levels, perpetuates outmoded conceptions of social life. Such conventions are evident also in other forms of symbolic expression, such as clothing. Lukmana says, ‘A religion teacher might wear a specific kind of clothing and speak in a certain way so that other people will recognise him as a religion teacher and treat him in the way he desires.’

|

Iwa Lukmana is a leading member of

|

In Lukmana’s view, the use of symbolic expression to organise status differences is a feature of all languages, and is found even in Indonesian. He points out that the national language has not functioned as the democratic tool some had hoped it would. The status-neutral second person pronoun anda, for example, introduced in an attempt at social engineering, has failed to catch on in daily use. Nevertheless, he believes that the use of symbolic expression for personal gain is more common amongst the Sundanese, and possibly the Javanese, than amongst other ethnic groups of Indonesia. The languages and social conventions of the Sundanese and Javanese are particularly rich in status signifiers such as titles, dress codes, speech levels and so on.

Lukmana’s interest in this subject stems also from his concern for the future of Sundanese. He is concerned that while the Sundanese language continues to express an outmoded social hierarchy, younger people will prefer to speak in the national language, Indonesian. Lukmana is not the first to take this position. The veteran Sundanese intellectual Ajip Rosidi has maintained strong opposition to the speech levels still used in Sundanese, arguing that many people find it difficult to ‘correctly’ express status difference. Rather than make a mistake and incur a social penalty, people prefer to speak Indonesian, which is a vastly more egalitarian language.

Reform is needed, according to Ajip and Lukmana, for Sundanese to become a suitable language for modern Indonesians. The alternative, according to Lukmana, is that the Sundanese language will ‘fall into a current of feudalism that is no longer in harmony with contemporary conceptions of social life’. ii

Julian Millie (Julian.Millie@arts.monash.edu.au) is a researcher in School of Political and Social Inquiry at Monash University.