Paige Johnson Tan

Suharto may no longer be the father of development, but he still

|

In March 2007, Indonesia’s Attorney General, Abdul Rahman Saleh, banned and ordered the burning of copies of 14 school history textbooks. Book burning? Isn’t this the reformasi era? Didn’t the resignation of President Suharto usher in a new era of freedom of expression? To be sure, a few democracy and truth-in-history activists spoke up against the book burning. But overall, the confiscations and burnings that have followed the Attorney General’s order have caused little more than a blip on Indonesia’s national radar.

According to the Attorney General, the books burnt in March 2007 made no reference to the ‘communist rebellion’ at Madiun in 1948, an event that anti-communists have long depicted as a stab in the back of the young Indonesian republic as it was fighting for its life against the Dutch. Also, the books did not state that the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) was responsible for the September 30th Movement (G30S in the Indonesian acronym), the murky coup attempt in 1965 which led to the downfall of Sukarno and the rise of Suharto. According to Indonesian law, school books must still refer to the September 30th Movement as ‘G30S/PKI’ (or similar expression), pinning the blame squarely on the PKI.

Suharto died at the end of January this year, yet Suharto-era interpretations of history continue to be taught to a new generation of school children in Indonesia. Strikingly, a deputy to the book-burning Attorney General suggested that the very ‘unity of the nation’ was at stake in the textbook affair. This was because the books challenged ‘accepted truths’ and posed the ‘latent danger of communism’.

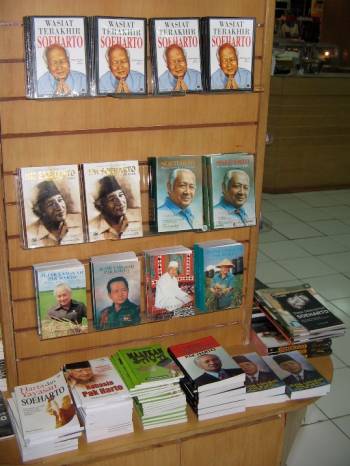

So how does the government want Indonesians to remember Suharto’s New Order regime and its origins in 1965? I went to a book store in Jakarta and randomly pulled off the shelves a sample of three history texts in order to find out. These books – whose lead authors were Magdalia Alfian, I Wayan Badrika and Purwanto – are typical of the kinds of histories being taught to school students in today’s Indonesia (see below for full bibliographical details).

The political economy of publishing

The way school book publishing works in Indonesia is that the Ministry of Education sets a common curriculum and then book publishers produce various texts that follow that curriculum. Each company hopes its text will be adopted by the schools. Typically, an author is given a short period of time, perhaps just one month, to update a text. Often the lead author divides the work among a number of colleagues, and this sometimes leads to a disjointed final product.

Suharto-era interpretations of history continue to be taught to a new generation of school children

The indifference to quality in textbook publishing is matched by indifference to history in the classroom. On average, students spend only about two hours a week on history. Because it is not one of the subjects tested in Indonesia’s important national examination system (it is tested only as part of the students’ end-of-year examinations), history is not considered very important by either teachers or students.

What I found in going through these three history books was that today’s textbooks could not be mistaken for textbooks of the Suharto era. It is true that much of the pre-1966 past remains as it was taught during the Suharto years. Incidents like the Madiun revolt in 1948 and the September 30th Movement in 1965 are still presented in terms of the old Suharto-era, anti-communist interpretations. However, there is greater variation in the treatment of the Suharto era itself. Particularly when describing how Suharto fell in 1998, some textbooks are more critical than others of the long-serving leader’s regime, highlighting its corruption and its undemocratic institutions.

The quick and slipshod manner in which authors compose textbooks in Indonesia probably accounts for such contrasting interpretations. Information about the pre-1966 period seems to have been cut-and-pasted from old Suharto-era texts into the new books. New information about recent events has then been added without any effort to create a consistent narrative. Sometimes several different interpretations exist side by side.

The debate over the teaching of history

In the reformasi era, scholars, government officials and history teachers have debated the teaching of history. Asvi Warman Adam at Indonesia’s Institute of Sciences (LIPI) has advocated greater balance. Since the 1965 coup plotters called themselves the ‘September 30th Movement’, he reasons, it would be neutral for textbooks to adopt the same language, instead of persisting with the ‘G30S/PKI’ moniker. Two of the three books I collected did on at least one occasion use just the ‘September 30th Movement’. One, by Badrika, mentions that the historian Hermawan Sulistyo wrote that this is what the coup plotters called themselves. Another, by Purwanto, uses the ‘September 30th Movement’ by itself, but then adds ‘G30S/1965/PKI’ in parentheses.

No text mentioned the mass killings that followed the September 30th Movement. Estimates vary as to how many were killed at this time, but John Roosa notes that more than one million people were ‘rounded up’ and that some of these detainees were executed (Inside Indonesia 91, January–March 2008 ). Two of the three textbooks I examined allude vaguely to the killings. One (Purwanto) states that the post-coup period was ‘coloured by acts of revenge, carried out by social groups such as pesantren [religious schools] or groups of military, especially the army’. Another (Badrika) asserts that ‘Soeharto, who became minister and head of the armed forces, took actions to clean up elements of the PKI and its mass organisations’. Readers need to use their imaginations to work out what really happened.

Dealing with the so-called ‘Old Order’, the period before 1966, the textbooks still adhere to the New Order version of history. According to these books, the Sukarno era was a time of political chaos and economic distress. During the years of parliamentary democracy (1950–59) political parties failed to cooperate for the common good of the nation, each asserting its own interests. Governments rose and fell, with each one barely agreeing on a common program before collapsing and being replaced. Sukarno’s hyper-politicisation of society, especially during his authoritarian Guided Democracy period (1959–65), led to neglect of the people’s living standards. Then, according to this New Order-style narrative, communists tried to seize power by force in 1965, so the military stepped in. The new regime responded to public demands that the PKI be disbanded and the government start focusing on people’s basic economic needs.

The chapters on the New Order generally stick to the Suharto-era story as well, highlighting the government’s development efforts, particularly the green revolution (using technology to advance crop yields) and industrialisation. Only one book (Purwanto) makes any effort to systematically analyse the nature of the New Order political system, and this comes only in the section on how the New Order fell, not in the section on the New Order itself.

The other books are content to give random facts about the New Order: that political parties were forced to merge, that Suharto was elected by the highest legislative body to the presidency, and so on. The books don’t describe the invasion of East Timor in 1975 as an invasion. Instead, they state that the former Portuguese colony had descended into chaos during decolonisation and Indonesia had to intervene to help it. According to one text (Badrika), there were various ‘processes’ and then East Timor was incorporated into Indonesia as the 27th province; there is no mention of 100,000-plus deaths.

Cut-and-paste history

One of these texts (Magdalia) most clearly appears to be the product of a group effort of cutting-and-pasting. The authors give the standard New Order explanation of the September 30th Movement. Then, apparently pasted in, there is a selection of alternative explanations of the action. The first explanation is that the PKI was responsible. Some limited evidence is offered. Other explanations are then explored: that the action was an internal conflict within the military, that Suharto led it, or that Sukarno knew about it in advance. Without evaluating these alternative explanations, the text just moves back to the New Order version of the story for its conclusion, again linking the PKI to the coup. It appears that in the time-pressed and responsibility-diffused process of Indonesian textbook production, the old text was simply rammed together with the new alternative explanations. The reader is left with the impression that the New Order narrative is still the correct one.

Information about the pre-1966 period seems to have been cut-and-pasted from old Suharto-era texts. Sometimes several different interpretations exist side by side.

Certainly, some changes have occurred in the writing of history in the reformasi period. Suharto has been brought down a step. He is no longer the great father of development. Textbooks at least include some alternative explanations for the 1965 coup, while not giving them much credence. They do not present East Timor as a great beneficiary of Indonesian largesse (roads, schools and clinics). One text mentions that some East Timorese did not agree with the territory’s incorporation and fought a guerrilla struggle. The books also highlight several problems of the Suharto regime, such as the silencing of the press, ideological indoctrination, corruption and jailing of political opponents. There is even a picture of activists of the radical People’s Democratic Party in one book. But these new interpretations are just scattered within the texts. The broader New Order story about communists, divisive parties and the military’s heroic role in unifying and saving the nation remains intact.

Why is it that the New Order interpretation of Indonesia’s early years is still in place, despite the fact that reformasi has turned Indonesia from a dictatorship into a democracy? Certainly, the process of textbook production, as described above, plays a role in the creation of Indonesia’s schizophrenic textbooks. But, it cannot explain why a policy decision such as the requirement to continue to refer to the 30th of September Movement as G30S/PKI would be made.

According to scholar and columnist Julia Suryakusuma, New Order interpretations of history such as this continue to dominate because history is an interpretation of events based on power. Many of those in power today first assumed prominence during the New Order, some as protégés of Suharto himself. Thus, these actors subscribe to many New Order assumptions and beliefs. Some New Order myths are fundamental to how contemporary actors see themselves. Many Muslims who killed communists in 1965–66 continue to believe that they did so in defence of their families, faith and nation. Military officials continue to make the case publicly that the suppression of the communists after the September 30th Movement saved Indonesia from a far worse fate.

Teaching and teachers

Andi Achdian, Director of the Onghokham Foundation, which is concerned with the teaching of history in Indonesia, held a seminar with teachers from around the country in February 2007. According to Andi, the teachers wanted to know the ‘right’ way to teach history now. During the New Order, there was just one government-approved way to teach history. Now, even if a lot of the story remains the same, teachers are more free to present and weigh alternative opinions. Some recoil from the new freedom. They are civil servants more comfortable with the certainty of old ways.

Many students have changed, though. They are empowered by the internet, searching out their own answers and bringing these into class discussions, according to both media reports and history experts. Alternative explanations for the 30th of September Movement proliferate on the web in both English and Indonesian, for example. The government no longer has a monopoly on information. Little wonder, then, that in response to the teachers’ questions about the right way to teach history now, Andi’s advice was ‘be creative’. ii

Paige Johnson Tan (tanp@uncw.edu ) is an assistant professor of political science at the University of North Carolina Wilmington in the United States. She writes on democratisation, political parties and transitional justice in Indonesia.

Textbooks Reviewed:

1. Magdalia Alfian, et al, Sejarah untuk SMA dan MA Kelas XII, Esis, 2003 (2006

curriculum standard contents).2. I Wayan Badrika, Sejarah untuk SMAL Kelas XII, Jakarta: Erlangga, 2006.

3. Purwanto, et al, Sejarah untuk SMA/MA Kelas XII IPS, Bekasi: PT Galaxy Puspa

Mega, 2006.