Denie Kasan

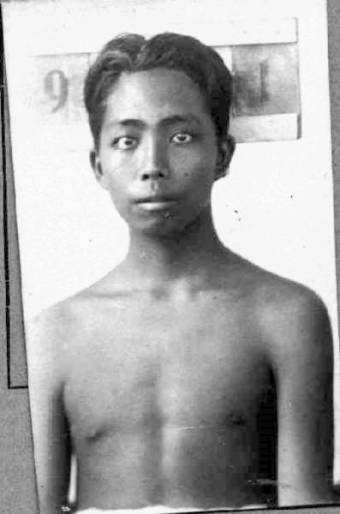

A picture of my grandfather when he first arrived in Suriname. |

In 1928, my grandfather, Soeparno, was 18 years old and looking for work in Ngawi, East Java. He heard about a well-paid job in a foreign country called Suriname. He thought he would work there a while and then return back to his family.

Little did he know that he was about to be caught in a system of indentured labour that would last until 1939. During this period 32,956 Javanese people like my grandfather were shipped to Suriname. Just a handful made it back to their homeland.

Peperpot - Dordrecht plantation

When he arrived in 1928, my grandfather discovered that work on the plantation was tough and the reality was harsh. Workers had no privileges and had to work long hours with little rest. Wages were inadequate and conditions were appalling, with poor food and no proper healthcare.

The Javanese felt betrayed as they believed they had been sent to work as free people making good money and had been promised a safe trip home. But in reality they were treated as slaves. They had to work six days a week and were refused days off. Saying no to work resulted in detention for breaking the terms of the contract. These contracts were drawn up by the plantation owners, commission members and judges.

There was a lot of resistance because workers were treated like slaves and had a poor life. There is at least one known incident of workers attacking and killing the plantation owner.

Even though life was hard, people tried to make the best of it. My grandfather met my grandmother and had six children with her. Each already had two daughters from a previous marriage so together they had a family of twelve.

The Netherlands

My black mother raised me and my two sisters on her own so I did not have frequent contact with the Javanese part of me. But growing up, my interest in Suriname’s history and genealogy increased with the years.

One day, my father took my sisters, a niece and nephew, and I to the National Archives in The Hague where there was a seminar on Javanese immigrants. That was the very first time I heard the full story.

The National Archives presented a database of Javanese immigrants and showed a preview of a special project to make a database of Chinese, Indian as well as Javanese contract workers. I was very enthusiastic about it all and couldn't wait for the project to finish. It was eventually completed.

Relatives in Java

I never have known my grandfather Soeparno. My father says he was a very religious and hard-working man. He was a very intelligent man who had respect for people and life in general. He never spoke about life in Indonesia and the life he had there, the family he left, or the friends he had. It was probably too painful to talk about. His heart was filled with regret and anger, maybe.

My father could never find the right time to talk to him about it. After my grandfather died, just before I was born in 1977, my father realised it was too late.

But what do I know of my grandfather? All we know is that his name was Soeparno. According to a younger sister of my father, my grandfather should have had brothers and sisters with names like Soeparman, Soepardi and Soeparmin. His father’s name should have been Soeparno also and his mother’s name was Remeh.

In my grandfather’s immigration document it states that he was from the village of Kendal in Ngawi district, Madiun. I don’t know if that is true. The information I have combined suggests that the descendents of my grandfather’s brothers and sister could still be alive. Maybe they live in Kendal, maybe in Ngawi, maybe in Madiun, or perhaps even in Semarang.

I’m hoping someone in Indonesia can help me set up this family tree and help me find living relatives of my grandfather Soeparno. ii

Denie Kasan (denie@live.nl ) lives in the Netherlands.