Brent Luvaas

Unkl 347’s distro in BandungBrent Luvaas |

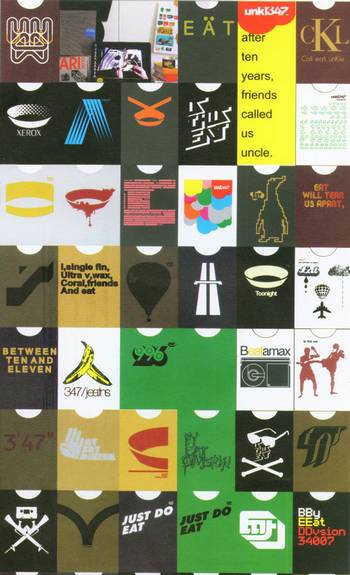

Dendy Darman, co-founder and owner of Bandung’s best-known independent clothing label, Unkl347 (or just 347 for short), has made a name for himself out of image theft. Not the back-alley variety, where name-brand designs are smuggled into dingy sweatshops and printed onto lower-grade, knock-off products, but the in-your-face, ‘Hey look what I did!’ kind, where other peoples’ designs are reworked and reasserted into public view.

347 is one of hundreds of independent clothing labels popping up all over urban Indonesia that use international commercial culture as the visual vernacular of their designs. These indie clothing brands appropriate foreign logos and remix borrowed imagery, tagging commercial iconography the way gangs mark their territory in the inner city.

These are not simply freelance design vigilantes taking what they can for whatever profit they can get. They see themselves as part of a movement of creative youth working to construct an alternative form of capitalism. Designers think of their activities as something like a youth takeover of national and international aesthetics, a collective reimagining of what it means to be young and modern.

Designer vandalism

Dendy’s company specialises in remixes of corporate logos; in appropriations of immediately recognisable commercial iconography. 347’s national reputation has been staked on a particular pieced together look, a punk-inspired aesthetic that is composed out of graphic collage but manages to look clean and sharp.

347 has sampled designs from such international brands as Pepsi, Xerox, Fuji, Microsoft, and Yellow Pages. They’ve borrowed rock ’n’ roll imagery from the likes of Suede, Joy Division, Oasis, the Rolling Stones, and the Velvet Underground. They routinely take inspiration from skate and surf brands like Rusty, Volcom, and Juice.

One of 347’s most popular designs is its ‘Xerox’ logo design. It features their own ‘bowl’ logo, immediately recognisable to many young Indonesians, disintegrating into pixilated dots, a blatant imitation of Xerox’s trademark ‘X’. The designers at 347 added the word ‘Xerox’ beneath the image just in case the reference is missed. The effect is jarring. When the viewer recognises the symbol of one brand exhibiting characteristics of another, they experience momentary visual confusion. In this design and others, 347 appears to have morphed into another brand. They have possessed it, taken it over. And in the process, the world’s biggest supplier of copying machines has become little more than a copy itself.

These are not simply freelance design vigilantes taking what they can for whatever profit they can get

Dendy’s most controversial design came out a few years back when the company was still called ‘Eat’. It featured the Nike swoosh logo with the word ‘Eat’ superimposed on top of it in big, bold letters. This design didn’t just copy the American brand’s logo. It claimed it as its own, marking it as the public property that in reality it had already become. And in the process, it asserted youth fashion as the province of Indonesian designers. Any foreign brand that dares to venture into Indonesian waters, the message read, had better be prepared to have their work stolen. In the world of Indonesian indie clothing design, all of global culture is fair game.

The cut ’n’ paste generation

|

Some of 347’s designsSuave Street Brand Catalogue, March 2007 |

Designers outside of Indonesia’s growing indie fashion scene have accused 347 of simply pirating other (far more successful) brands’ merchandise. They say that 347 are copycats – or, worse still, lazy designers. But according to Dendy, those critics are missing the point. 347 never intended to pass the Nike design off as their own, or ride the coattails of an international sporting gear giant. The design is commentary, not a copy.

‘We’ve been cut ’n’ paste from the beginning, and now is the era of cut ’n’ paste,’ Dendy told me as we sat in his office – a converted industrial space – in southern Bandung, sipping sweetened jasmine tea through thin plastic straws. ‘We readily admit it,’ he says. ‘In fact, we make it obvious so that people know.’ One of 347’s designs, for instance, features an almost exact copy of the album cover for ‘Goo’ by the New York art punk band Sonic Youth. A young, modish couple in bowl cuts and sunglasses smoke cigarettes while they lounge in each other’s arms. Beside the image, the original handwritten words ‘I stole my sister’s boyfriend’ have been replaced with ‘I stole my Sonic Youth.’

For Dendy, the important thing is not whether a designer takes ideas from someone else. Everyone does that. Some just admit it more readily than others. What matters is whether a designer is ‘conscious’ of what they are doing. Consciousness, Dendy claims, is what separates the pirates – the low-level capitalists popping up in city streets and dimly-lit warehouses throughout the archipelago – from the cut ’n’ pasters like him.

Cut ’n’ paste, as Dendy sees it, is an act of conscious reworking that gives the imagery of contemporary life – the transnational brands, the bands played on MTV – local resonance and meaning. Like samplers in hip-hop and collage artists from the Dadaist era, cut ’n’ paste designers like Dendy create new compositions out of materials someone else has constructed.

Design in the digital age

Young designers like Dendy attribute their cut ’n’ paste methodology to the DIY (do-it-yourself) practices of punk rock: the self-altered clothing of 1970s British street kids, the photocopied, cut-up aesthetics of early ’zines. This practice surfaced in Indonesia in the 1990s through mail-order catalogues and imported magazines and has been growing since.

The Internet, widely available in Indonesia by around 1996, made cut ’n’ paste not only more common, but far easier to do. It provides easy tools for lifting an image from the visual vaults of popular culture and using it in one’s own. All aspiring young designers need to do to set up shop is to acquire a working computer, often assembled piecemeal from a roving discount electronics fair, load it up with pirated design software like Corel Graphics Suite (available street-side for a mere Rp7,000 (A$0.78), and start sifting through the databanks of Google Images for usable prototypes of whatever design they want to make. Once created, designs can be reproduced cheaply by local clothing production houses, or for the scrappier and more hardcore, printed freehand with a homemade silkscreen.

It should not be surprising, then, that so many independent clothing labels began springing up in Indonesia in the late 1990s, as the economy faltered and the Internet became readily available. Middle-class kids could no longer afford the foreign fashions they had become accustomed to, and decided to make them for themselves. Today, there are hundreds, if not thousands of independent clothing labels in Indonesia, run, designed, and owned by youth. Their wares, sold at stylish, youth-operated shops called ‘distro’ (see Uttu’s article in the Jan-Mar 2006 issue), are some of the most popular brands among teenagers and university students.

And what began as a hobby quickly became an industry: Companies like 347 bring in as much as Rp1 billion per month, and are beginning to expand into the neighbouring countries of Malaysia, Singapore, and even as far as Australia.

Making it for themselves

The impact of indie clothing lines is not simply economic or aesthetic. It’s also cultural. Indie fashion democratises youth style, promoting the idea that anyone with access to a personal computer can be a designer – whether they have formal training or not, whether they can draw or not – and fostering a DIY ethic, where getting into the fashion game is as easy as cutting ’n’ pasting.

Indie designers remix global culture for a local audience. They use the international fashion industry as a resource for self-creation, with the iconography of commercial culture providing the visual fodder for new design. In the process, they are constructing a new conception of Indonesian youth culture, in which the measure of cool is no longer one’s ability to be hip to the latest trends or buy the most fashionable clothes. These days, the coolest kids are the ones who make them for themselves. ii

Brent Luvaas (luvaas@ucla.edu ) is a recovering fashion victim and a current PhD candidate in Anthropology at UCLA.