Paul Barber

Jetty at Babo, looking towards Bintuni BayLiem Soei Liong |

The Tangguh Liquid Natural Gas project in West Papua province, operated by the UK multinational BP, is one of Indonesia’s largest foreign investment projects. According to BP, it involves the extraction of around 14.4 trillion cubic feet of gas from six fields near Babo in the Bintuni Bay area of the Bird’s Head region over a period of 25-30 years, at a cost of between US$5.5 to US$6 billion. An entire community of over 120 households and more than 650 people has been relocated to make way for the project facilities on the south shore of Bintuni Bay.

Indigenous residents had no real say in whether the project should go ahead

BP claims that Tangguh has been designed and implemented with a view to ensuring corporate social responsibility and compliance with international human rights standards. The company employs sophisticated public relations techniques to convey the message that, although local people are experiencing massive changes to their lives, overall the development will benefit those living nearby and Papuans in general.

However, the indigenous residents had no real say in whether the project should go ahead. The principle of Free Prior and Informed Consent– whereby indigenous peoples have the right to decide to accept or reject a project on their land – was never applied to them.

A number of key issues remain unresolved which are a source of potentially serious problems.

Human rights concerns

Anecdotal reports point to increased activity in the area by police and army special forces and intelligence agents. A company of around 100 troops has been permanently deployed to Bintuni town, police numbers are set to increase, and there are plans to establish a small naval base in Bintuni Bay. Although Bintuni town is some distance from the Tangguh site, it is reasonable to assume that the troop deployment is related to the project development. The past record of the Indonesian military (TNI) suggests that those seeking to protect the rights of local communities may be stigmatised as ‘separatists’ and will be vulnerable to intimidation if not more serious consequences. The security forces afford a higher priority to protecting business interests than defending local livelihoods.

Ominously, the Indonesian National Defence Institute is conducting an assessment of security in the area in anticipation of Tangguh operations. It is considering whether to recommend upgrades to the local police posts and sub-district military commands. A panel set up by BP to advise on the non-commercial aspects of the project has warned that the situation could become less stable if new police or TNI units are stationed in the Bintuni area.

|

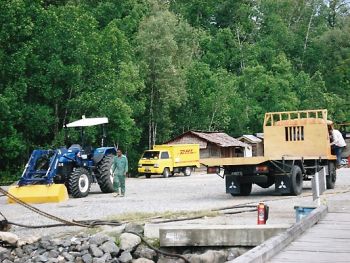

Quayside, BaboLiem Soei Liong |

BP has attempted to forestall human rights problems by operating an Integrated Community Based Security (ICBS) programme, which uses a community policing system in cooperation with the local police. The credibility of the programme was called into question, however, when it transpired that an agreement between BP and the police had been signed by a police commander, Timbul Silaen, indicted on crimes against humanity charges in East Timor. BP is keen to proclaim the success of ICBS, but it has not yet been tested by an incident deemed to threaten Tangguh as a national strategic asset. Human rights would be at severe risk if the military is brought in to respond to such an incident.

Disrupted livelihoods

The resettled south-shore villagers have seen some material benefits from the provision of new housing and infrastructure, but the longer-term impact of the social upheaval on their livelihoods is uncertain. Access to gardens and forest resources in the vicinity of their former village and to traditional fishing grounds is no longer possible. One villager has complained that they are now living in ‘gilded cages’, expensive homes with empty kitchens and nothing to cook. BP argues that such an opinion is not representative and points to the steps it has taken to compensate or assist affected villagers. Despite that, some villagers have been unable to adapt to their new livelihoods and have decided to sell their new houses and move out of the area.

There is ongoing tension among non-resettled villagers who feel they have been unfairly treated by BP. This applies in particular to villagers on the north shore of Bintuni Bay who claim customary rights over some of the gas being exploited. In addition, there are tensions and unresolved disputes over claims to land affected by the project.

The demobilisation of up to 10,000 construction workers, who include more than 6,000 in-migrants from other parts of Indonesia, will have to be carefully handled if problems are to be avoided. Less than 2,000 people will be employed during the operating phase. As they will include a higher proportion of managerial and skilled workers, the long-term employment prospects for unskilled Papuans are not promising.

Environmental impact

|

Mangroves near BaboLiem Soei Liong |

Tangguh is located in the middle of a sensitive coastal ecosystem with the world’s third largest mangrove area. A degree of degradation is inevitable no matter how careful BP is to ensure minimal impact. Its record in other parts of the world, which includes responsibility for the largest oil spill in Alaska’s history, does not inspire confidence.

Also of concern is the problem of CO2 emissions. Around 12.5 per cent of the Tangguh gas reserves consist of CO2, which will be ‘vented’ into the atmosphere unless it can be reinjected into the ground. There is currently no agreement between BP and the Indonesian government to proceed with a technical appraisal of reinjection. The expectation now is that the CO2 will be vented into the atmosphere for at least the first four years of operations.

Who benefits?

It can be reliably assumed that the project will generate huge profits for the shareholders of the operating companies and substantial tax revenues and royalties for the Indonesian government. The Papuan people should receive a 70 per cent share of the royalties under special autonomy provisions, but no benefit will accrue to them until after the project costs have been recovered around 2016. The Indonesian government is currently attempting to renegotiate its LNG sales contract with China to reflect worldwide price increases, but the Papuans are not given any say in these talks and it is not clear whether they will gain from improved terms.

Some Papuans would argue that Tangguh, far from being beneficial to them, is yet another resource curse

There is confusion about how the Papuans’ share of the royalties will be allocated given the controversy over the division of the territory into the two provinces of Papua and West Papua and the lack of clarity over how revenues derived from West Papua province will be apportioned under special autonomy. Until recently, the special autonomy legislation did not apply to West Papua province. Even now, seven years after its introduction to Papua, it is generally accepted that special autonomy has not been properly implemented and has failed to address key human development needs such as improved access to health and education services.

Some Papuans would argue that Tangguh, far from being beneficial to them, is yet another resource curse, whereby the presence of natural resources may actually cause more problems than benefits for local people. They regard the project as an obstacle to them realising their right to self-determination and BP as a collaborator with Jakarta’s exploitation of their natural resources. There is the risk, therefore, that Tangguh will represent a potential source of instability in the region until these concerns are addressed and Papuan rights are fully realised. It is in BP’s interests not only to respect Papuan rights, but also to actively promote them in the widest possible context, for example by lobbying against local and regional security upgrades. At the same time, the project must be closely monitored and international pressure maintained at every stage of the process to ensure that BP accounts for its impact on local communities and the Papuan population in general.

The company has rather pretentiously claimed that Tangguh aspires to be a ‘world class model for development’. It remains to be seen whether it will regret giving this hostage to fortune by the problems that will undoubtedly arise during the course of Tangguh’s operations. ii

Paul Barber (plovers@gn.apc.org) is research and advocacy coordinator for TAPOL, which promotes human rights, peace and democracy in Indonesia.